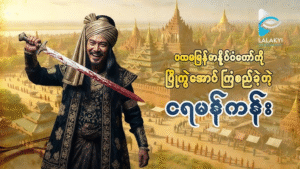

King Alaungsithu and His Indian Connection: Chronicle, Tradition, and Historical Memory

According to the Glass Palace Chronicle (Hmannan Yazawin), King Alaungsithu of Pagan was intimately connected—by destiny, lineage, and karmic rebirth—to the royal house of Pateikkaya, a kingdom believed to have been located in eastern India or the Bengal–Chin frontier region.

The Chronicle Account of a Former Life

The Chronicle records that in a former existence, King Alaungsithu had been the son of the king of Pateikkaya (an Indian kingdom). When he learned of the forced marriage of Princess Shwe Einthi to Prince Saw Yun, instead of to the Pateikkaya prince she loved, he fell from the sky at a place called Wa and died of grief.

Later, when Shin Arahan, the great Theravāda reformer of Pagan, collected the bones of this deceased prince, a miraculous event occurred. The spirit of the prince—destined to be reborn as Alaungsithu—appeared with a fourfold army, took possession of the bones, and cast them into the water at the shore of Nyaung-U. He then made a solemn vow:

“If these are truly my bones, let them float upon the water.”

According to the Chronicle, the bones floated, confirming his claim. The bones were then retrieved and enshrined with reverence at Shwegu Pagoda, in what the Chronicle calls “the land of conquest.”

This episode is recorded in the Glass Palace Chronicle, section 120, under Bones of the Prince of Pateikkara.

Shwe Einthi: The Human Link Between Pagan and Pateikkaya

Princess Shwe Einthi (Burmese: ရွှေအိမ်သည်; also rendered Shwe Einsi) was the only daughter of King Kyansittha (r. 1084–1113), one of Pagan’s greatest monarchs. She occupies a poignant place in Burmese historical memory, not merely as a royal consort, but as a tragic figure caught between political obligation and personal affection.

Soon after Kyansittha ascended the throne, Shwe Einthi fell in love with a visiting prince from Pateikkaya, widely believed by scholars to have been from eastern Bengal or the Indo-Burman frontier. Kyansittha, however, forbade the marriage, refusing to allow his daughter to wed a foreign prince. Instead, she was married to Prince Saw Yun, the son of the late King Saw Lu.

The primate Shin Arahan himself conveyed this decision to the Pateikkaya prince. According to tradition, the prince was devastated by the news and took his own life, an act remembered not merely as a personal tragedy but as a karmic turning point that would later shape Pagan history.

Alaungsithu: Birth, Succession, and Meaning

Shwe Einthi bore two sons with Saw Yun:

- Soe Saing

- Sithu, later known as King Alaungsithu, who succeeded his grandfather Kyansittha.

While biologically Alaungsithu was the grandson of Kyansittha and the son of Saw Yun, the Chronicle emphasizes a karmic and spiritual lineage connecting him to the Indian royal house of Pateikkaya. This dual identity—Burman by birth, Indian by karmic origin—is a recurring theme in Pagan historiography and reflects the cosmopolitan nature of early Burmese kingship, where legitimacy was drawn not only from bloodline but from merit accumulated across lifetimes.

Historical Interpretation

Modern historians generally treat the former-life narrative as symbolic rather than literal, yet it remains historically significant for what it reveals:

- Pagan’s close cultural and political contact with India

- The acceptance of Indic royal legitimacy within Burmese Buddhist thought

- The presence of Indian princes, monks, and ideas at the Pagan court

- The role of Theravāda Buddhism in framing kingship through karma and rebirth

Thus, while Alaungsithu may not have been biologically the son of the Pateikkaya prince, Burmese royal tradition explicitly regarded him as such in a previous existence, a belief solemnized by ritual, miracle, and monumental architecture.

Conclusion

King Alaungsithu stands as a powerful example of how history, religion, and memory intertwine in Burmese chronicles. His story reflects not racial purity or isolation, but interconnectedness—between Burma and India, between love and loss, and between past lives and present rule. Far from diminishing Burmese identity, this narrative underscores the plural, inclusive, and transregional foundations of Pagan civilization.

NOTE:

The mention of a Pateikkaya or “Patikera state” in ancient Bengal likely refers to a historical misinterpretation or an alternative name for the ancient kingdom of Harikela.

Scholars previously read the legend on some ancient “bull and triglyph” coins, discovered in the Mainamati region, as “Patikera”. This reading led to the assumption that an independent state by that name existed. However, this legend has now been correctly and widely accepted by scholars as reading “Harikela“.

The Kingdom of Harikela

- Location: The ancient kingdom of Harikela was situated in eastern Bengal, primarily covering the modern-day Sylhet and Chittagong divisions of Bangladesh, as well as parts of Tripura state in India and South Assam.

- Significance: It was an independent political entity that maintained a continuous existence for about 500 years and was a significant part of the ancient geopolitical landscape of Bengal, alongside other Janapadas (territorial divisions) like Vanga, Suhma, and Samatata.

- Archaeology: The discovery of a vast collection of Harikela coins, some belonging to ancient Arakan kings, helps place its location near the border of Samatata and towards Arakan (modern-day Rakhine State in Myanmar).