Malaysian Christian Engineer Lecturer Mr Ian Chai wrote:

𝘖𝘯 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘯 𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘵 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘭𝘢𝘸 𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘰𝘥 𝘶𝘱 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘦𝘴𝘵 𝘑𝘦𝘴𝘶𝘴. “𝘛𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘳,” 𝘩𝘦 𝘢𝘴𝘬𝘦𝘥, “𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘮𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘐 𝘥𝘰 𝘵𝘰 𝘪𝘯𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘪𝘵 𝘦𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘯𝘢𝘭 𝘭𝘪𝘧𝘦?” “𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘸𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘓𝘢𝘸?” 𝘩𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘱𝘭𝘪𝘦𝘥. “𝘏𝘰𝘸 𝘥𝘰 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘥 𝘪𝘵?” 𝘏𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘥, “‘𝘓𝘰𝘷𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘓𝘰𝘳𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘎𝘰𝘥 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘵 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘴𝘰𝘶𝘭 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘵𝘩 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘢𝘭𝘭 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘮𝘪𝘯𝘥’; 𝘢𝘯𝘥, ‘𝘓𝘰𝘷𝘦 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘯𝘦𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘣𝘰𝘳 𝘢𝘴 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘴𝘦𝘭𝘧.’” “𝘠𝘰𝘶 𝘩𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘴𝘸𝘦𝘳𝘦𝘥 𝘤𝘰𝘳𝘳𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘭𝘺,” 𝘑𝘦𝘴𝘶𝘴 𝘳𝘦𝘱𝘭𝘪𝘦𝘥. “𝘋𝘰 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘭𝘪𝘷𝘦.” 𝘉𝘶𝘵 𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘥 𝘵𝘰 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘧𝘺 𝘩𝘪𝘮𝘴𝘦𝘭𝘧, 𝘴𝘰 𝘩𝘦 𝘢𝘴𝘬𝘦𝘥 𝘑𝘦𝘴𝘶𝘴, “𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘪𝘴 𝘮𝘺 𝘯𝘦𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘣𝘰𝘳?” – 𝘓𝘶𝘬𝘦 10:25-29 Then Jesus tells the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

When modern readers encounter the parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke’s Gospel, they typically hear a heartwarming story about helping strangers. The word “Samaritan” has become so sanitised in our language that hospitals and charitable organisations proudly bear the name. We’ve lost the parable’s original shock value entirely.

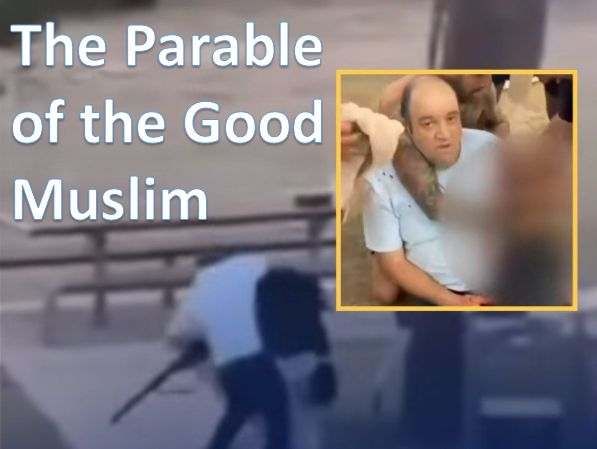

Then something extraordinary happened on December 15, 2024, at Bondi Beach in Sydney, Australia. A Muslim man named Ahmed al-Ahmed did something that suddenly made Jesus’ ancient parable blazingly relevant again—and in doing so, revealed exactly what made the original story so scandalous.

𝐖𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐇𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐭 𝐁𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐢 𝐁𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡

During a Hanukkah celebration at Bondi Beach, two men opened fire, killing 15 people and wounding at least 42 in what authorities are calling an antisemitic terrorist attack. In the chaos and terror, as people fled and fell, Ahmed al-Ahmed, a 43-year-old Syrian-Australian Muslim fruit shop owner and father of two, was having coffee with a friend when he heard the gunshots.

Video footage shows what happened next. Al-Ahmed sneaked up behind one of the gunmen, grabbed him and wrestled away his firearm. He then pointed the weapon at the attacker before setting it on the ground and raising his hands. During this act of courage, al-Ahmed was shot twice by the second gunman, suffering injuries to his shoulder and hand.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese called al-Ahmed’s actions “an example of Australians coming together,” noting that he “took the gun off that perpetrator at great risk to himself and suffered serious injury as a result.” Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump praised him, with Trump calling him “a very, very brave person” who had saved many lives. A GoFundMe campaign has raised over $2 million for his recovery.

But here’s what makes this story a perfect modern parallel to the Good Samaritan: Ahmed al-Ahmed, a Muslim, risked his life and was wounded saving Jews from an antisemitic attack.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐄𝐧𝐦𝐢𝐭𝐲: 𝐉𝐞𝐰𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐒𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐬

To understand why this matters, we need to grasp what Jesus’ original audience heard when he said “Samaritan.” The hostility between Jews and Samaritans in the first century wasn’t merely theological disagreement or cultural difference. It was a centuries-old hatred rooted in religious schism, territorial disputes, and mutual accusations of apostasy.

Samaritans were viewed by Jews not simply as outsiders, but as heretics who had corrupted true worship. They were descendants of those who had intermarried with foreign colonisers, built a rival temple on Mount Gerizim, and rejected the authority of Jerusalem. To first-century Jews, Samaritans represented religious contamination and political betrayal.

The animosity was deeply personal and immediate. Jewish travellers would go miles out of their way to avoid passing through Samaria. The Talmud records that Samaritan testimony was inadmissible in Jewish courts. Some Jewish texts of the period describe Samaritans in language reserved for enemies and apostates. This wasn’t ancient history—it was lived experience, the prejudice absorbed from childhood and reinforced by community boundaries.

When Jesus made a Samaritan the hero of his parable, he wasn’t choosing a random foreigner or a distant enemy. He was choosing the enemy, the religious other who lived close enough to hate intimately, the neighbour who represented everything that faithful Jews believed threatened their covenant identity. The priest and Levite who pass by the wounded man in Jesus’ story aren’t merely callous individuals—they represent the religious establishment itself, the very people who should embody covenant faithfulness.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐌𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐏𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐥: 𝐀𝐡𝐦𝐞𝐝’𝐬 𝐒𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲

For many Western Christians and Jews today, particularly those shaped by post-9/11 anxieties, decades of Middle Eastern conflict, and rising antisemitism often associated with Islamic extremism, Muslims occupy a strikingly similar psychological space to Samaritans in the first century. This parallel isn’t about theological equivalence—it’s about emotional response and cultural positioning.

Consider the layers of meaning in Ahmed al-Ahmed’s actions:

• A Muslim saving Jews during a Hanukkah celebration

• Stopping an antisemitic terror attack

• Being wounded while protecting people celebrating a Jewish holy day

• His Syrian origin adding another layer, given Syria’s complex relationship with Israel

• The global response transcending religious boundaries

As Prime Minister Albanese noted, the actions of the attackers were “completely out of place with the way that Australia functions as a society,” which he contrasted with al-Ahmed’s response. But there’s something deeper happening here. In a world where many people—consciously or unconsciously—associate Islam with violence and particularly with antisemitism, Ahmed al-Ahmed’s heroism shatters categories exactly as the Good Samaritan’s compassion did.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐥 𝐑𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝

Jesus told his parable to answer the question “Who is my neighbour?” The lawyer asking the question wanted to limit his obligation, to draw a circle around those deserving care. Jesus’ answer exploded that circle entirely. The neighbour isn’t defined by shared religion, ethnicity, or tribal loyalty. The neighbour is whoever shows mercy. And most scandalously, the person who shows mercy—who truly understands covenant love—turns out to be the religious outsider.

Ahmed al-Ahmed’s story recovers this scandal for modern ears. When we hear “Good Samaritan” today, we miss the offense—we’ve domesticated the story into a platitude about random acts of kindness. But when we see a Muslim saving Jews from an antisemitic attack, when we watch him being shot while protecting a Hanukkah celebration, when we hear his father say “My son is a hero, he has the passion to defend people”—we feel something of what Jesus’ original audience felt.

This is uncomfortable for everyone. For those who harbour anti-Muslim prejudice, it challenges the narrative that Muslims are inherently violent or antisemitic. For those invested in interfaith conflict, it demonstrates that religious identity doesn’t determine moral action. For everyone, it forces a reckoning: the person we might have viewed with suspicion or fear demonstrated greater courage and compassion than most of us will ever be called to show.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐑𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧

The parable of the Good Samaritan ends with Jesus asking “Which of these three do you think was a neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” The lawyer has to answer “The one who had mercy on him.” He can’t even bring himself to say the word “Samaritan.”

Ahmed al-Ahmed’s story poses the same question to us: Who was neighbour to the Jews being murdered at their Hanukkah celebration? The answer is undeniable—and it’s meant to be uncomfortable. It’s meant to shatter our categories, to challenge our prejudices, to force us to recognise righteousness where we didn’t expect to find it.

Al-Ahmed’s mother said, “I’m proud that my son was helping people, rescuing people. He saw they were dying, and people were losing their lives.” This is covenant love in action—not defined by religious boundaries but by the fundamental recognition of human dignity and the willingness to sacrifice for others.

Jesus’ parable wasn’t a nice story about being kind to strangers. It was a prophetic provocation designed to destabilise religious certainty and ethnic prejudice. Ahmed al-Ahmed didn’t intend to create a modern parable—he simply saw people in danger and acted. But in doing so, he became what the Good Samaritan was to the first century: living proof that God’s mercy flows through unexpected channels, that righteousness isn’t confined to our religious boundaries, and that the people we’ve demonised may understand divine love better than we do.

The question Jesus leaves us with is the same one his original audience faced: Will you let your prejudices prevent you from recognising righteousness? Will you allow religious boundaries to override human compassion? Will you acknowledge that the “enemy” might be more faithful to God’s heart than you are?

Ahmed al-Ahmed, recovering from gunshot wounds sustained while saving Jewish lives during Hanukkah, has already answered these questions with his body. The rest of us are still deciding how to respond to his modern parable.

𝐀 𝐏𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐎𝐮𝐫 𝐌𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭

If Jesus were telling the story today, He might say: “A man was attacked, beaten, and left for dead. A pastor passed by. A worship leader passed by. But an Arab Muslim immigrant stopped, risked his life, and saved him.”

The shock would be the point.

Not to elevate Islam. Not to deny Christian truth claims. But to expose the lie that our group has a monopoly on compassion.

Jesus chose the Samaritan precisely because it made the point unavoidable. There was no way to hear the parable and maintain comfortable categories. You couldn’t say “Well, of course the religious people passed by, but at least one of our own helped.” The helper was the enemy. That was essential to the story’s power.

Ahmed al-Ahmed does the same for us. His heroism cannot be domesticated or explained away. A Syrian Muslim immigrant physically wrestling a gun away from an attacker targeting Jews celebrating Hanukkah—this is not a story that lets anyone off the hook. It confronts anti-Muslim prejudice directly. It challenges assumptions about who embodies righteousness. It forces the question: if a Muslim can risk his life for Jews, what excuse do we have for our indifference, our prejudice, our carefully maintained boundaries?

“𝐆𝐨 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐃𝐨 𝐋𝐢𝐤𝐞𝐰𝐢𝐬𝐞”

The command at the end of the parable is not “Go and believe likewise.” It is “Go and do likewise.”

Jesus doesn’t ask the lawyer to change his theology about Samaritans. He doesn’t require him to accept Samaritan worship practices or validate their religious claims. He commands him to imitate the Samaritan’s compassion. The parable’s genius is that it separates theological correctness from moral excellence—and insists that the latter matters more than we want to admit.

Ahmed al-Ahmed did go and do likewise. He saw people dying and acted. He didn’t calculate whether they shared his faith or his politics. He didn’t weigh whether saving them would complicate his standing in his community. He simply saw human beings in mortal danger and responded with his body, his courage, his willingness to be wounded.

This is what covenant love looks like when it’s not theoretical. This is mercy when it costs something. This is the kingdom of God breaking into our world through the most unexpected messenger.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐑𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐬

𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘑𝘦𝘴𝘶𝘴 𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘷𝘦𝘴 𝘩𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘪𝘯𝘨—𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘯𝘰𝘸—𝘪𝘴 𝘸𝘩𝘦𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘤𝘭𝘢𝘪𝘮 𝘏𝘪𝘴 𝘯𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘩𝘦𝘢𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘺, 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭 𝘰𝘧𝘧𝘦𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘥, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘮𝘰𝘷𝘦 𝘰𝘯… 𝘰𝘳 𝘳𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘨𝘯𝘪𝘴𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮𝘴𝘦𝘭𝘷𝘦𝘴 𝘪𝘯 𝘪𝘵 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘳𝘦𝘱𝘦𝘯𝘵.

Will we see ourselves in the priest and Levite, those whose religious obligations somehow prevented them from stopping? Will we acknowledge that our theology, our church involvement, our biblical knowledge might actually be what keeps us from recognising righteousness when it appears in unexpected forms? Will we admit that we’ve constructed a narrative where Muslims are the problem, and any story that complicates that narrative must be explained away or minimised?

Or will we let this story do what Jesus’ parable was meant to do—break our hearts open, shatter our certainty about who the good people are, and drive us to our knees in recognition that God’s mercy is wilder and more generous than we’ve allowed?

Jesus chose the Samaritan because the Samaritan made the point unavoidable. Ahmed al-Ahmed does the same. His story cannot be absorbed into comfortable categories. It demands a response. It forces a choice.

And that is why his story feels like a parable we did not want—but desperately need.

The priest and Levite probably had good reasons for passing by. Religious purity laws. Important responsibilities. Pressing appointments. Jesus wasn’t interested in their reasons. He was interested in who stopped.

We have good reasons too. Theological differences. Security concerns. Cultural anxiety. Complicated geopolitics. Jesus, we can be fairly certain, isn’t interested in our reasons either. He’s interested in who acts with mercy when mercy is costly.

Ahmed al-Ahmed acted. He was shot twice doing it. He’s now recovering, praised by world leaders, supported by millions in donations—but the real gift he’s given us isn’t his heroism alone. It’s the mirror he holds up, the question he forces us to answer: When the moment comes, who will we be? The ones who pass by with our reasons, or the ones who stop?

The parable ends with a command: “Go and do likewise.” Not “Go and believe correctly.” Not “Go and maintain proper boundaries.” Do likewise. Act with mercy. Risk something. Be neighbour.

Two thousand years later, a Syrian Muslim immigrant showed us what that looks like. The question is whether those of us who claim to follow the One who told the original parable will have the humility to learn from it.