Moe Thauk wrote:

Myanmar’s civil war is a deeply tragic and painful conflict. It is often described as a struggle against “Bamar majoritarianism” among ethnic groups. However, while reading news about fighting between Karen and Bamar forces, what is truly unheard of is seeing ethnic conflicts spill over into physical fights inside restaurants. This reveals something important: this war is essentially a conflict among ethnic elites, feudal lords, and war leaders, while ordinary people are reduced to nothing more than expendable grass trampled underfoot. Only when seen this way does the situation begin to make sense.

From the very beginning, even agreements among ethnic elites were fragile and conditional. As the saying goes, at the Panglong Conference itself, unity could only be negotiated by granting the right to secede after ten years. In essence, this is not very different from two people signing a marriage contract that already includes a clause allowing divorce after ten years—legally speaking, the logic is quite similar.

In the entire world, among nearly 200 countries, fewer than five were established with an explicit constitutional right to secession. Examples often cited include the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Ethiopia—and all of these eventually collapsed or fragmented. Most countries, by contrast, do the opposite: they clearly state in their constitutions that there is no right to secession. A few countries avoid stating explicitly either “the right to secede” or “absolutely no secession,” leaving the matter ambiguous.

Why, then, was the “right to secede” demanded so strongly and treated almost as an inherent right? Historically, this demand is said to have come mainly from the Shan saophas (local feudal rulers). Their argument was that the hill regions were “separately administered free areas” under colonial rule and were not subjugated in the same way as the Bamar lowlands. Therefore, they claimed, they did not urgently need independence. It was only because the Bamar side insisted on Panglong-style negotiations that the Shan rulers agreed to join the Union—on the condition that the right to secede be granted.

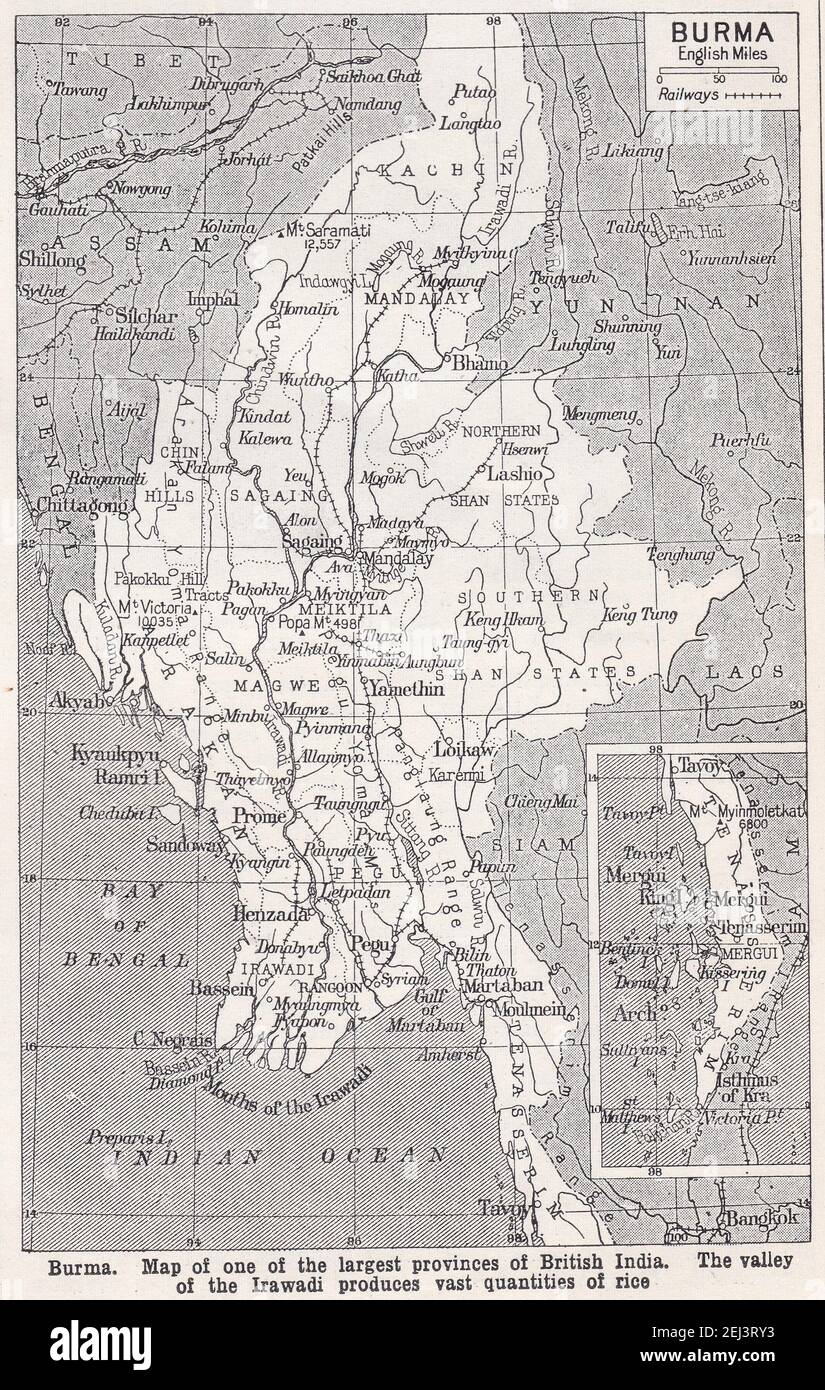

But was it really true, as the Shan feudal rulers claimed, that the Shan regions were never under colonial rule? Direct colonial administration, perhaps not—but indirect control certainly existed. Through the Burma Frontier Service (BFS), junior British officers acted as advisers to the saophas and effectively administered the saopha-controlled townships and districts. Although the saophas claimed they ruled independently, under the 1888 Shan States Act, the BFS had the authority to appoint, suspend, or dismiss them.

A key point—often overlooked even today by armed ethnic elites—is that the hill regions were not fully independent while only “Burma Proper” fell under colonial rule. Before 1937 (when Burma was separated from British India), the BFS reported to the Burma Province Commissioner; after 1937, it reported to the Governor of British Burma. In other words, while the saophas appeared to enjoy a degree of autonomy, even disputes between saopha territories were handled by the BFS. They had no authority over foreign border affairs involving China or Thailand. Simply put, they were not sovereign rulers. They were not fully independent.

Furthermore, even before 1937, when Burma itself was merely a province under British India, the BFS was not directly under New Delhi but under the Burma Commissioner. This shows that the hill regions were never completely separate states free from the Burmese central administration. Before 1937, Burmese affairs were handled by the Viceroy in New Delhi through the Burma Commission; after 1937, by London through the Governor of Burma. Throughout this entire period, the hill regions were consistently administered by the central government based in Rangoon.

Therefore, while the “right to secede” under the Panglong Agreement may carry political symbolism and negotiating value, it is difficult to argue that it was a strong or natural demand from an administrative or legal perspective. Yet it is this very political promise that continues to be used as justification for armed conflict—and it is ordinary people who continue to suffer its consequences, without end.

As CDM Judge Daw Thinzar Mya remarked:

“If we cannot do good things for them, then at least let them do it for themselves.”

My response under the main post:

With great respect, Honorable CDM Judge Daw Thinzar Mya, it may be useful to look at comparative models—especially Australia, Malaysia, and even Singapore—to understand how unity, promises, and fairness can be managed without force.

Take Australia as an example. The Australian government does not merely “return” mining income in a symbolic way. Mining royalties and taxes are a major source of revenue for States and Territories, funding hospitals, schools, roads, and public services—accounting for roughly 5% of state revenue. At the federal level, mining-related taxes are used for national projects and strategic investments, including international supply-chain security initiatives such as the US–Australia Critical Minerals partnership.

The benefit-sharing channels are clear and institutionalized:

- Direct royalty payments to states

- Federal grants for infrastructure and services in mining regions

- Targeted bailouts for strategic assets (such as copper smelters)

- Investment in downstream processing and value-added industries through international partnerships

Debates over profit-sharing still exist, but the key point is this: benefits do flow back to states and local communities. This is a model worth studying.

Malaysia offers another important lesson. Malaysia allowed Singapore to secede peacefully from the federation. That painful political decision ultimately led to stability, progress, and prosperity for both sides—something extremely rare in post-colonial history.

More importantly, Malaysia is now implementing long-delayed constitutional commitments. Under the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63), Sabah is entitled to a special annual grant equal to 40% of the net federal revenue derived from Sabah, as enshrined in Article 112C of the Federal Constitution. This provision was a key condition for Sabah joining Malaysia, intended to ensure fair revenue sharing for development. Decades of delays led to disputes and recent court actions over arrears for the “lost years.” Still, the principle stands: agreements matter, even decades later.

Historically, the Malay Sultans were also allowed to govern their states under British rule through a system of “indirect rule.” British Residents or Advisers had to be consulted on all matters except Islam and Malay customs. In practice, they wielded significant administrative power, while the Sultans remained the legal and symbolic heads. This arrangement later evolved—after painful political lessons—into today’s constitutional monarchy. The key lesson again: power-sharing and respect for local authority, even when imperfect, prevent total collapse.

This is why it is crucial for the majority to keep its promises.

As the Burmese saying goes:

“မင်းမှာ သစ္စာ၊ လူမှာ ဂတိ”

(A ruler must kept the Noble Truths; a person must keep promises.)

The majority must persuade minorities, reassure them, and make them feel secure and respected—not attempt to subdue them by force.

General Aung San’s famous promise—“Kayin ta kyat, Bamar ta kyat” (one kyat for the Karen, one kyat for the Bamar)—has sadly become a bitter joke.

On 12 February 1947, all the ethnic groups of Burma (now Myanmar) shared a dream when they signed the Panglong Agreement: the dream of forming a genuine Union of Burma based on equality and trust. That dream later turned into a dreadful nightmare under successive military regimes—and continues to haunt the present.

His Royal Highness Prince Hso Khan Pha (Tiger Yawnghwe), the eldest son of Sao Shwe Thaik, Saopha of Yawnghwe (Nyaung Shwe) and the first President of independent Burma, expressed it best:

“Might I add that the problem that exists is not ethnic ‘minority’ rights versus ‘majority’ Burmese rights, but rather the equality of rights for all.”

That, in the end, is the real unfinished business of Panglong.