‘Rebranded junta’ plans Myanmar polls with 30 ex-army as civilian candidates

Following Malaysia’s optimism over the Myanmar military regime’s professed “cooperation” in peace talks, and its agreement to an immediate ceasefire, insiders are warning not to fall for what they call the junta’s “ceasefire charm offensive”.

According to the Myanmar Employers Organisation (MEO), the junta’s strategy to rebrand its rule involves fielding at least 30 senior military officers as election candidates and staging participation in a 27-group dialogue to create the illusion of cooperation before the December polls.

‘A sham election’

The junta said its election objectives are for a “genuine, disciplined multiparty democratic system and the building of a union based on democracy and federalism.”

But with most of the country’s pro-democracy lawmakers in exile or jail, and the military’s widespread repression and attacks on the people, such a vote would never be considered free or fair, observers say.

“It’s a sham election… It’s not inclusive, it’s not legitimate,” Mi Kun Chan Non, a women’s activist working with Myanmar’s Mon ethnic minority, told CNN.

Many observers have warned that Min Aung Hlaing is seeking to legitimize his power grab through the ballot box and rule through proxy political parties.

“He needs to make himself legitimate … He thought that the election is the only way (to do that.),” said Mi Kun Chan Non.

The United States and most Western countries have never recognized the junta as the legitimate government of Myanmar, and the election has been denounced by several governments in the region – including Japan and Malaysia.

A soldier from the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force (KNDF), a main armed group fighting the military, walks to a reconnaissance mission. Thierry Falise/LightRocket//Getty Images

A collective of international election experts said a genuine election in Myanmar “is impossible under the current conditions,” in a joint statement released by the umbrella organization International Idea. The experts pointed to “draconian legislation banning opposition political parties, the arrest and detention of political leaders and democracy activists, severe restrictions of the media, and the organization of an unreliable census by the junta as a basis for the voter list.”

Others say they cannot trust the military when it continues its campaign of violence, and when its history is littered with false promises of reform.

Voting in a war zone

Details on the election process are thin, but many citizens could be casting their votes in an active conflict zone or under the eyes of armed soldiers – a terrifying prospect that some say could lead to more violence.

Junta bombs have destroyed homes, schools, markets, places of worship and hospitals, and are a primary cause of the displacement of more than 3.5 million people across the country since the coup.

There are fears that those in junta-controlled areas will be threatened or coerced into voting. And some townships may never get to vote, given the junta’s lack of control over large swathes of the country outside its heartland and major cities.

One of the country’s most powerful ethnic armed groups, the Arakan Army, has said it will not allow elections to be held in territories it controls, which includes most of western Rakhine state.

In pictures: Aung San Suu Kyi

37 photos

Aung San Suu Kyi poses for a portrait in Yangon, Myanmar, in 2010. A month earlier, she had been released from house arrest. Drn/Getty Images

And the National Unity Government, an exiled administration which considers itself the legitimate government of Myanmar, has urged the people to “oppose and resist” participating in the poll, saying the junta “does not have the right or authority to conduct elections.”

There are also signs the military is moving to consolidate its power in those parts of the country it does not control. As it rescinded the nationwide state of emergency, it also imposed martial law in more than 60 townships – giving the military increased powers in resistance strongholds.

“The military has been pushing hard to reclaim the territories it has lost, but regaining consolidated control — especially in the lead-up to the elections — will be a near impossibility within such a short timeframe,” said Ye Myo Hein, a senior fellow at the Southeast Asia Peace Institute, based in Washington DC.

“Instead, holding elections amid this perilous context is likely to trigger even greater violence and escalate conflict nationwide.”

Already, there are moves to further quash dissent ahead of the poll.

A new law criminalizes criticism of the election, threatening long prison sentences for those opposing or disrupting the vote. And a new cybercrime law expands the regime’s online surveillance powers, banning unauthorized use of VPNs and targeting users who access or share content from prohibited social media sites.

Like ‘putting old wine in a new bottle’

Min Aung Hlaing recently formed a new governing body, the National Security and Peace Commission (NSPC), replacing the previous State Administration Council.

The junta chief also has added chairman of the new regime to the roster of titles he now holds, which includes acting President and chief of the armed forces. And the new interim administration is stacked with loyalists and active military officers.

The move was “nothing more than an old trick — putting old wine in a new bottle,” said Ye Myo Hein.

“The military has used such tactics many times throughout its history to create the illusion of change… The military junta, led by Min Aung Hlaing, remains firmly in the driver’s seat.”

It has been here before.

Myanmar has been governed by successive military regimes since 1962, turning a once prosperous nation into an impoverished pariah state home to some of the world’s longest running insurgencies.

A military soldier (L) stands in front of a pile of seized illegal drugs during a destruction ceremony in Yangon on June 26, 2025. Sai Aung Main/AFP/Getty Images

In 2008, the military regime pushed ahead with constitutional reform that paved the way for a semi-civilian government to take power, while preserving its significant influence on the country’s politics.

What followed was a decade of limited democratic reform and freedoms that brought greater foreign investment –- including the return of global brands like Coca-cola – and engagement with western nations. A generation of young Myanmar nationals began to dream of a different future to their parents and grandparents, as investment and opportunities poured in.

But the military never really gave up political power.

When state counselor Aung San Suu Kyi’s party stormed to a second term victory in the 2020 election, it came as a surprise to some military figures, who had hoped their own proxy party might take power democratically.

The former democracy icon was detained during a coup the following year, tried by a military court and sentenced to 27 years in prison. The 80-year-old’s exact whereabouts is still a tightly guarded secret, and the junta has sought to ensure Suu Kyi and her popular, but now dissolved, NLD party would be politically wiped out.

International recognition

By presenting itself as a civilian government, analysts say the military will also try to convince some countries to normalize ties.

Russia and China are two of Myanmar’s biggest backers, and Thailand and India have pushed for more engagement with the junta to end the crisis on their borders.

China’s foreign ministry last Thursday said it “supports Myanmar’s development path in line with its national conditions and Myanmar’s steady advancement of its domestic political agenda.”

In recent weeks, Min Aung Hlaing had unexpectedly good news from the US.

A letter from the Trump administration detailing its new tariff rates was spun domestically by the junta leader as increased engagement.

Then, the Trump administration dropped sanctions on several companies and individuals responsible for supplying weapons to Myanmar, prompting outcry from the UN Special Rapporteur for Myanmar Tom Andrews who called the moved “unconscionable and a major step backward for efforts to save innocent lives.”

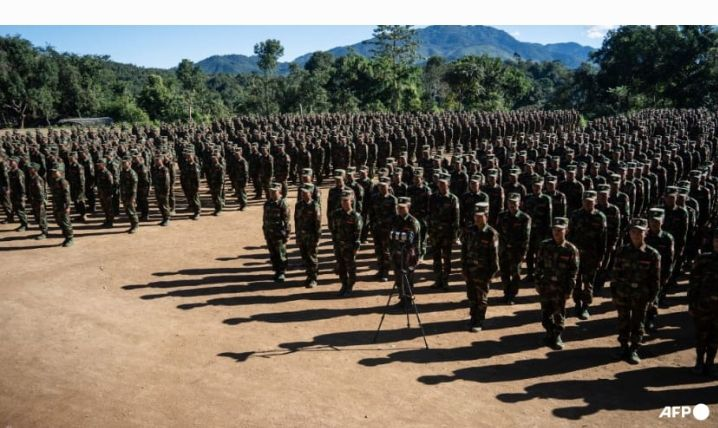

Members of Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) receive military equipment after getting special combat training in a secret jungle near Namhkam, Myanmar’s northern Shan State on November 9, 2024. Stringer/AFP/Getty Images

Myanmar’s Ministry of Information has also signed a $3 million a year deal with Washington lobbying firm DCI Group to help rebuild relations with the US, Reuters news agency recently reported. The group, as well as the US Treasury Department, the US State Department, and Myanmar’s Washington embassy did not immediately respond to Reuters’ requests for comment.

Democracy supporters opposed to the junta have warned the international community against falling for the military’s election plan, and say such a poll will never be accepted by the people.

Min Aung Hlaing and his junta “have sucked all the resources and money than can and the country has nothing left,” said Mi Kun Chan Non, the women’s activist.

“Everything has fallen apart … The education system has collapsed; the healthcare system has collapsed. Business is just for the cronies.”

So, any future peace negotiations that follow the elections, “we can never trust,” she said.

“And the situation of the people on the ground will not change.”