Nicola Williams (@MsNicolaSW) is a Ph.D. scholar at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy, working on a dissertation book project, “How Civil Conflicts End.” She has 14 years of professional experience in international development specializing in governance, conflict resolution, and fragility, including half a decade working in Myanmar.

A Political Settlement

There is currently no bargaining space between the Myanmar junta and the National Unity Government, which both seek to defeat each other militarily and have irreconcilable visions for the future of the state. There will not be a grand track-one negotiations process mediated by third parties or the United Nations anytime soon.

The United States and ally countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, and Japan — as well as China — have supported the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in seeking a political solution to the crisis. The group’s leaders continue to flog a five-point consensus on Myanmar, featuring a cessation of hostilities and dialogue among “all parties,” which one prominent analyst called “dead on arrival.” Given numerous bargaining problems and commitment challenges, there has, unsurprisingly, been no traction.

It is crucial for countries on the sidelines to learn from the peace process which took place in Myanmar for 10 years before the coup. This process spent years on life support and failed to transition the country from its military-designed hybrid system of unitary government to a civilian-controlled federal democracy, as desired by the many groups involved and their constituents. During this process, the military proved incapable of moving outside its own constitutional framework and self-serving interests to remain in politics. On the one hand, they played an obstructionist role, trying to inflame factional divides and exercise a veto over negotiations. On the other hand, they broke ceasefires, carried out assaults, and committed genocide against the Rohingya population.

Negotiating with the military for power-sharing is a plane that has already crashed into a hill. To shift the junta’s current warpath, significant institutional, cultural, and leadership changes are necessary to align the military’s vision for Myanmar with that of the population’s. This normative revolution from within is not going to happen anytime soon.

High-level diplomatic meetings with the junta’s Commander-in-Chief emphasizing the rule of law, human rights, and dialogue will not transform the policy of an institution designed for coercive control of populations, organized violence, and war-making. Western diplomats and regional leaders should only aim to deal with the junta later when it is politically and militarily weakened or closer to being unseated.

Several Western countries are already offering some level of aid and support to the National Unity Consultative Council, a coalition bringing together a complex array of stakeholders, including the National Unity Government, some ethnic armed groups, and civil society. This process has demonstrated promise, using national and subnational dialogue to design a democratic federal charter. Yet it is also struggling to bring together many ethnic groups. On the whole, it is unlikely a single process will solve all of Myanmar’s state-building and nation-building challenges. Many different peace dialogues and efforts will be needed.

State Failure and the ‘Balkanization’ of Myanmar

Numerous papers and articles have vaguely cited the possible “Balkanization” of Myanmar, stemming from state collapse or failure. While total state collapse is a rare event globally, cases of institutions collapsing and the state failing to perform its essential functions have plagued Myanmar for decades under military rule. Currently, the military cannot consolidate its control through subnational and local governance due to resistance from within state institutions, including boycotts by civil servants and defections from the security sector, not to mention armed attacks and citizens refusing to pay taxes.

In the “Balkanisation” scenario, a weak or collapsed center would lead to fragmentation and multiple separate ethnic states or fiefdoms. However, it is unlikely that any of the ethnic armed groups seeking independence would gain the type of foreign sponsorship necessary to pursue formal independence, as in the case of Kosovo, Timor-Leste, or South Sudan. Most countries on the sidelines of this crisis wish Myanmar would sort itself out and have no interest in making a complicated situation more challenging.

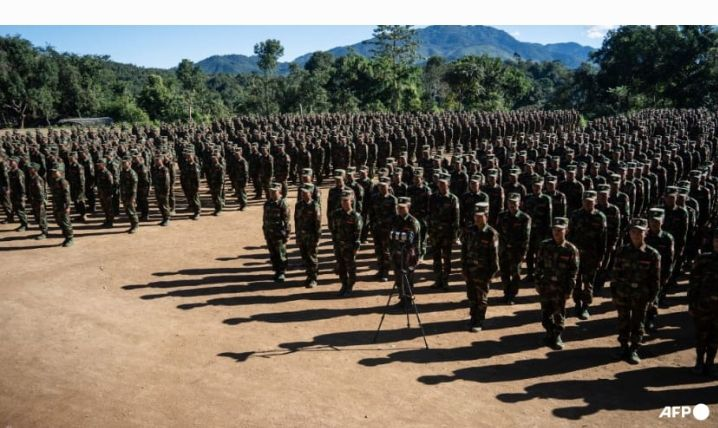

However, in the coup’s aftermath, ethnic armed groups have broadened and strengthened their control of territory. It is conceivable that existing ethnic fiefdoms could gain further autonomy and refuse to join a future civilian-led central government. Some armed groups that are already running de facto independent statelets and not aligned with the National Unity Government — such as the United Wa State Army, the ethnic Kokang Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Arakan Army — may continue to stay outside of the proposed federal charter. Groups may even “declare” independence without formal recognition.

In short, while full Balkanization is unlikely, fragmentation is a constant risk in Myanmar politics. This highlights the need for reconciliation between leaders from ethnic minorities and the Bamar majority.

Protracted Low-Intensity Conflict

There is one more scenario to consider. It is also possible that after several years of battles without a decisive outcome, the revolutionary movement could transform into a protracted, low-intensity conflict alongside the other ethnic conflicts in Myanmar. In this scenario, a military and political stalemate would lead both the National Unity Government and the military to retreat without a strategic or decisive outcome to the conflict.

While such stalemates can sometimes be opportunities for political negotiations, the Myanmar military has shown that they prefer to have infrequent fighting than commit to any form of power-sharing. Without the demands of an intense armed conflict, rebel groups often evolve. Full-time forces may be reduced to reserves and some armed actors may seek out other economic opportunities.

A long stalemate or low-intensity conflict in the Bamar heartland would be a minor victory for the military. This would mark a return to the status quo, with multiple conflicts that the junta could manage in sequence. Resistance forces and ethnic armed groups should work strategically to prevent this by stretching the military’s resources as far as possible and for as long as possible while better integrating their own supply chains.

Conclusion

What can the United States and its regional partners do to support an opposition victory? Given the risks of a costly quagmire with Russia and China, they are unlikely to provide lethal military assistance. Instead, they can provide the National Unity Government with more aid to build its civilian institutions and direct aid to support opposition political structures in the most conflict-affected parts of the country. Foreign countries should also reinvest political capital in dialogue platforms to improve elite relations between ethnic armed groups and Bamar civilian leaders, and support discussions on governance systems to manage Myanmar’s complex ethnic jigsaw.

The year ahead is a critical time for the National Unity Government, its armed allies, and ethnic armed groups seeking to create a federal democracy in Myanmar. If the United States and its Asian allies want a strategic partner instead of a chaotic pariah state, now is the time to take greater risks and engage more effectively with the opposition government and rebel groups.