“The Gateway to Pagan: Rediscovering the Maritime Ties of the Bay of Bengal”

By Dr. Ko Ko Gyi @ Abdul Rahman Zafrudin | MMNN Editorial

Few realize that the story of Pagan’s grandeur is not confined to the Irrawaddy plains—it stretches far across the Bay of Bengal, touching the shores of Malaya, India, and Sri Lanka. Recent reflections and historical fragments reveal a vibrant maritime network that once connected Melaka, Bago, Tanintharyi, and even the Pashu Peninsula, forming a forgotten corridor of cultural and commercial exchange.

Melaka: A Port of Many Peoples

Melaka’s founding was not a singular Malay endeavor. It was a cosmopolitan port, shaped by Malays, Arabs, Indonesians, Dutch, and—surprisingly—Bago men. Historical accounts suggest that at least 20 ships from Bago regularly entered Melaka, indicating a robust bilateral trade. These voyages likely carried Mon textiles, Buddhist manuscripts, and coastal goods, while returning with spices, ceramics, and Islamic influences.

Alaungsithu’s Voyage to the Pashu Peninsula

The Glass Palace Chronicle records that King Alaungsithu of Pagan journeyed to the Pashu Peninsula—a term believed to refer to the Bajau Malays of the southern Tanintharyi coast. This royal voyage, en route to Sri Lanka, underscores Pagan’s diplomatic and religious outreach across the Indian Ocean. It also hints at early Malay settlements in lower Burma, possibly linked to the Bajau seafarers who navigated these waters long before colonial maps were drawn.

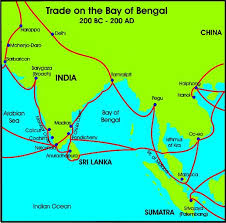

The Chola Empire’s Maritime Shadow

A map of the Chola Empire reveals its reach across the entire Bay of Bengal coastline—from Tamil Nadu to Burma, Malaya, and Indonesia. This was not mere conquest; it was a maritime cultural diffusion, where Tamil merchants, Buddhist pilgrims, and Hindu temple builders left their imprint. The Chola naval expeditions likely passed through Tanintharyi and Bago, reinforcing the idea that Burma’s coast was part of a pan-Asian maritime highway.

“Pagan Gateway” Reimagined

The term “ပုဂံ အဝင်တံခါး” (Gateway to Pagan) may not refer to a gate within Pagan itself, but rather to foreign ports like Melaka or Selangor, where travelers changed ships before heading inland. This poetic naming reflects Burmese maritime memory, recognizing distant harbors as symbolic thresholds to the kingdom’s spiritual and economic heart.

Conclusion: A Call to Reconnect

These fragments—ships from Bago in Melaka, Alaungsithu’s coastal diplomacy, and Chola imperial maps—invite us to reimagine Pagan not as isolated, but as interwoven with the Indian Ocean world. MMNN encourages scholars, students, and storytellers to dig deeper into these maritime legacies, and to restore Burma’s coastal history to its rightful place in the chronicles of Asia.

Rediscovering “Fukan Tuoluo” as Pagan Dwara

- The term “ဖူကန်တွာရာ” appears in ancient Chinese records, possibly as “Fukan Tuoluo” or “Fukan Tulu”, depending on transliteration.

- Paul Pelliot, the renowned French sinologist, noted that the Chinese characters could phonetically render both “Fukan Tuoluo” and “Fukan Tulu”, with the former aligning more closely to “Pagan Dwara”—meaning “Gateway to Pagan.”

- Luce leaned toward “Fukan Tulu”, but failed to clarify what “Tulu” referred to, despite acknowledging “Fukan” as Pagan.

Burmese Historiography and U Ye Yint Sein’s Contribution

- Burmese historian U Ye Sein focused on “Fukan Tuoluo”, asserting it refers to “Pagan Dwara”, a symbolic or literal gateway to Pagan.

- This interpretation aligns with Chinese diplomatic and trade records, which often described foreign kingdoms by their entry points or coastal access, not just their capitals.

Pyu = Brahma = Burma?

- Ancient Indian and Bengali sources referred to the region as “Brahma Kingdom”, inhabited by Brahma people.

- Chinese records, however, used “Pyu Kingdom” and “Pyu people” to describe the same civilization.

- This linguistic overlap suggests that Pyu = Brahma, and thus Pyu Kingdom = Burma.

- Consequently, Sri Ksetra and Pagan—both Pyu cities—are reaffirmed as part of Brahma/Burmese civilization.

Supporting Evidence from Inscriptions and Trade Routes

- The Tharaba Gate bilingual inscriptions at Pagan, analyzed by Liu Yun, show Chinese–Pyu diplomatic contact, reinforcing Pagan’s visibility in Chinese records.

- The Pyu city-states, including Sri Ksetra and Beikthano, were active from the 2nd century BCE to the 11th century CE, overlapping with Pagan’s rise.

- Pagan’s role as a spiritual and trade hub made it a recognizable entity in Chinese maritime and overland records.

Conclusion: A Forgotten Name, Rediscovered

“Pagan Dwara” was never heard in Burmese history but found in Chinese records is a breakthrough. It challenges the assumption that Pagan was isolated from Chinese historiography and highlights the importance of phonetic interpretation in cross-cultural studies. MMNN could lead the way in reviving this narrative, bridging Burmese, Chinese, and Indian historical memory.

Historical Insight to Remember

- Mon/Talings were early migrants from Talingana (India).

- They intermixed with ancient local inhabitants of Burma—whose identities remain unidentified but are acknowledged by Burmese historians.

- Mon-Khmers, possibly originating from Tibetan highlands, also migrated southward and contributed to the cultural-linguistic fabric.

- Intriguingly, one of the six Orang Asli groups in Malaysia (the indigenous peoples akin to Aboriginals) speaks a language that is derived from or related to Mon-Khmer—suggesting deep prehistoric ties across the Bay of Bengal and Southeast Asia.

This memory adds a powerful layer to our long-term goal of building a literary and historical archive that honors the shared roots and resilience of Myanmar’s diverse communities.

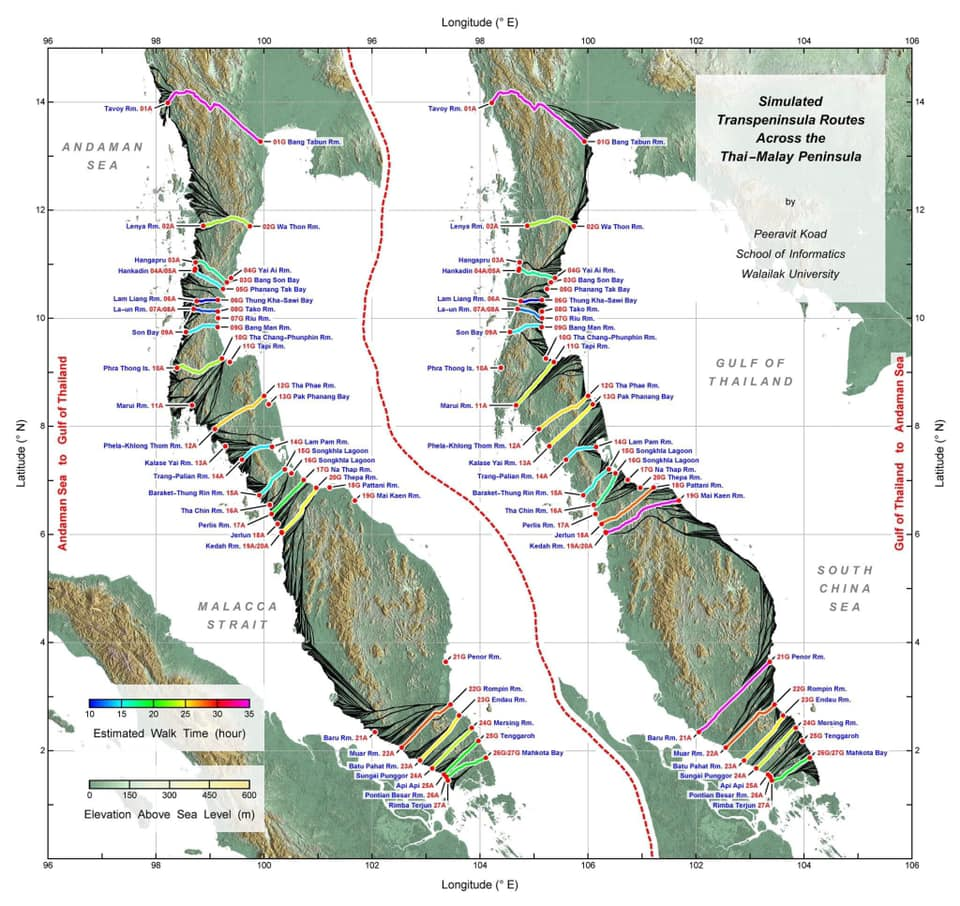

Examining trade routes through the Thai–Malay Peninsula: A simulation analysis

via Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 22 July 2024: A simulation analysis using a digital elevation models explores early trade routes across the Thai–Malay Peninsula, revealing potential transpeninsula paths that could connect historical records and archaeological sites. The study identifies five zones based on these routes and suggests areas for future archaeological discoveries, enhancing understanding of early human movement and trade in Southeast Asia.

An important area for understanding human movement and trade routes during the Early Historic Period in Southeast Asia is the Thai–Malay Peninsula where external records date back 2300 years. Early east–west trade could be routed around the peninsula or sailing time could be reduced by taking terrestrial shortcuts across the peninsula. However, spatial research, particularly on transpeninsula routes, is insufficient to supplement the gaps between written historical records and excavated archaeological sites. This study aimed to simulate transpeninsula routes across the entire Thai–Malay Peninsula using a digital elevation model (DEM) to eliminate human biases when exploring the actual terrain. The simulation results reveal some intriguing characteristics of potential routes that can be used to divide the Thai–Malay Peninsula into five zones. This zonation is associated with external historical records and archaeological evidence before the twelfth century AD to assess the efficacy of different transpeninsula routes. These data are also utilized to propose potential areas of undiscovered archaeological sites within the Thai–Malay Peninsula.