By Jeffrey Tin Ohn (R.I.T – Rangoon Institute of Technology)

Editor’s Note:

This reflective essay, originally written by Jeffrey Tin Aung of M-Media, examines the controversy surrounding an early statement by Myanmar’s Minister for Religious Affairs in 2016, which appeared to question the citizenship status of Muslims and Hindus. With careful reference to historical records, the author calls for truth, fairness, and responsibility from national leaders — reminding us that Myanmar’s diverse faith communities have long been part of its national fabric.

Time to Change — and Time to Reflect

When the National League for Democracy (NLD) campaigned under the slogan “Time to Change,” it inspired citizens across Myanmar — people of all ethnicities, faiths, and social backgrounds — who were yearning for an end to dictatorship.

On 1 April 2016, their votes made history as power shifted peacefully to a new civilian government.

Soon after, on 2 April 2016, Voice of America (VOA) aired an interview with Thura U Aung Ko, the newly appointed Minister for Religious Affairs and Culture. During that interview, he remarked that during past military regimes there had been no suppression or discrimination against minority faiths such as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or other small religions.

That statement, however, caused deep hurt and disappointment among Myanmar Muslims — both among those officially recognized as national races and those categorized as “associate citizens.” Many saw the comment as a betrayal from a government they had supported with great hope. Some viewed it as a stab in the back, others as a deliberate denial of their long struggle for recognition.

The four major religions in Myanmar today — Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and Hinduism — were all introduced from abroad. The only indigenous beliefs of ancient Myanmar were forms of nat (spirit) worship. Religion, in its true essence, teaches moral conduct and purpose in life. It should never divide people by race, color, or class. In a civilized world, there is no such thing as a “host religion” or “guest religion.”

Historical Truth vs. False Claims

The minister’s later claim — that most Muslims were descendants of immigrants who arrived only during the British colonial period — was not only unsupported by evidence but also contradicted official historical records, including those produced by the military government itself.

For instance, during the SPDC era in 1997, the Ministry of Defence published a book titled “To Illuminate the Light of Religion.” On page 65, it clearly stated that Islam reached Myanmar over 1,000 years ago, long before British annexation.

Likewise, the University Journal of July 1973 (Vol. 3) confirmed that Muslim Pathi (Pashi) people lived during the Pagan (Bagan) period, supported by ancient stone inscriptions.

Historians such as Zeya Kyaw Htin Ba Shin, teacher of NLD leader Thura U Tin Oo, wrote in “How the Ancient Burmese Kings Honoured Their Muslim Subjects” that Burmese Muslims were granted royal privileges and recognized by early monarchs.

Similarly, Dr. Than Tun, in his studies of royal edicts, listed the Muslim Pathi people among the 18 recognized ethnic groups in Myanmar’s chronicles — the Hmannan Yazawin (Glass Palace Chronicle), Konbaung Chronicle, and U Kala’s Chronicle.

During the British, Japanese, and AFPFL (post-independence) periods, the state officially recognized Myanmar Muslims (မြန်မာမွတ်စလင်) as a legitimate national community. The term “Bamar” referred to the nation as a whole, not a single ethnic group.

Furthermore, a 23 February 1973 state newspaper listed 143 ethnic groups, among which Myanmar Muslims were officially included.

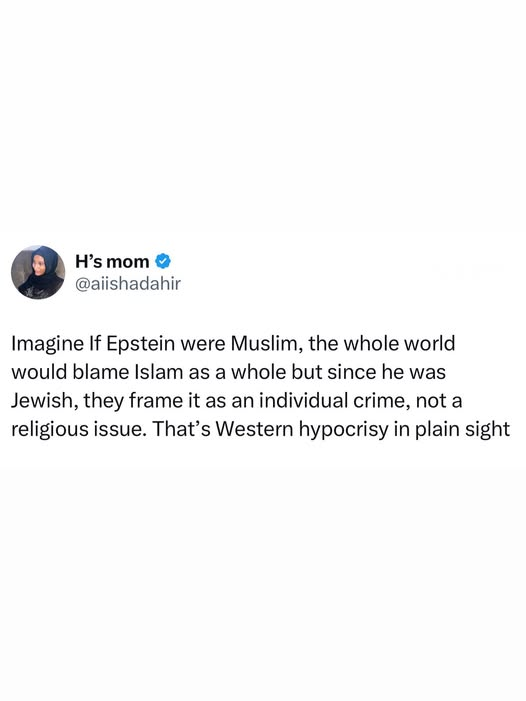

Thus, citizenship cannot — and must not — be determined by religion. No government, especially one that has seized power unlawfully, holds the right to define who belongs based on faith.

Citizenship, Equality, and the Spirit of Aung San

Only laws passed by elected representatives through legitimate democratic processes can define citizenship. When the Religious Affairs Minister carelessly described Buddhists and Christians as national races but labeled Muslims and Hindus as guest citizens, he gravely undermined the image of the government and the nation.

By contrast, in a press briefing on 31 July 2012, then Minister for Immigration U Khin Yi clearly stated that “Before 1824, there were no foreigners in Myanmar.”

This statement affirms that all communities living in the country before British rule were native inhabitants, not foreigners. It stands as undeniable historical evidence.

In building a democratic nation, racial or religious discrimination is like a nuclear bomb — highly unstable and capable of destroying the country at any moment.

This truth was well understood by General Aung San, the father of Myanmar’s independence and founder of the armed forces. He reminded his comrades:

“Do not think that only we love our country. Whether here or abroad, it is not only soldiers who love the nation.”

He further declared:

“Since the time of King Alaungpaya, there have been Muslims in our land. There are followers of the Bahá’í faith, mountain dwellers who worship spirits, and Christians whose faith is deep-rooted. All of them are citizens of our country. When we fought for independence, it was not only we soldiers who took part — they too fought alongside us.”

Leadership and Responsibility

Those words reveal the broad vision, intelligence, and moral strength of a true national leader. They reflect a deep understanding of unity, responsibility, and justice.

No human being, no matter how skilled, is infallible — as the saying goes, “There is no perfect lawyer, nor an immortal doctor.” Likewise, ministers can make mistakes.

The comments made in that VOA interview should therefore not be seen as the official stance of the NLD, a party that rose to power through the people’s trust. More likely, they were unintentionally influenced by the long legacy of discriminatory thinking that persisted under successive military regimes.

To acknowledge a mistake is the mark of a true and wise leader. History has shown that when errors are made in good faith and later corrected, the public forgives.

The key is to recognize and correct wrongs quickly — before they grow into lasting injustice.

By Jeffrey Tin Ohn (R.I.T – Rangoon Institute of Technology)

Originally published in M-Media; edited and adapted for MMNN English Edition.