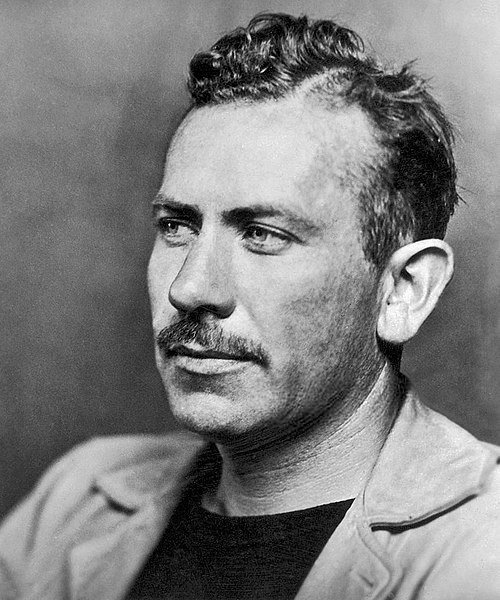

John Steinbeck from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

John Ernst Steinbeck (/ˈstaɪnbɛk/ STYNE-bek; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer. He won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature “for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social perception”.[2] He has been called “a giant of American letters.”[3][4]

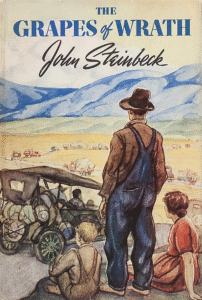

During his writing career, he authored 33 books, with one book coauthored alongside Edward Ricketts, including 16 novels, six non-fiction books, and two collections of short stories. He is widely known for the comic novels Tortilla Flat (1935) and Cannery Row (1945), the multigeneration epic East of Eden (1952), and the novellas The Red Pony (1933) and Of Mice and Men (1937). The Pulitzer Prize–winning The Grapes of Wrath (1939)[5] is considered Steinbeck’s masterpiece and part of the American literary canon.[6] By the 75th anniversary of its publishing date, it had sold 14 million copies.[7]

Much of Steinbeck’s work employs settings in his native central California, particularly in the Salinas Valley and the California Coast Ranges region. His works frequently explored the themes of fate and injustice, especially as applied to downtrodden or everyman protagonists.

Steinbeck followed this wave of success with The Grapes of Wrath (1939), based on newspaper articles about migrant agricultural workers that he had written in San Francisco. In August 1936, the San Francisco News asked Steinbeck to personally interview multiple families in the impoverished Hoovervilles of the San Joaquin Valley. As Steinbeck visited the slums that hugged the highways across the Central Valley, he was harrowed by what he saw. He talked with multiple families and vowed to make a book depicting their struggles. It is commonly considered his greatest work. According to The New York Times, it was the best-selling book of 1939 and 430,000 copies had been printed by February 1940. In that month, it won the National Book Award, favorite fiction book of 1939, voted by members of the American Booksellers Association.[27] Later that year, it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction[28] and was adapted as a film directed by John Ford, starring Henry Fonda as Tom Joad; Fonda was nominated for the best actor Academy Award. Grapes was controversial. Steinbeck’s New Deal political views, negative portrayal of aspects of capitalism, and sympathy for the plight of workers, led to a backlash against the author for displaying communist views, especially in his hometown of Salinas.[29] Steinbeck received so many threats that he purchased a handgun for his own safety. Claiming the book both was obscene and misrepresented conditions in the county, the Kern County Board of Supervisors banned the book from the county’s publicly funded schools and libraries in August 1939. This ban lasted until January 1941.[30]

Of the controversy, Steinbeck wrote, “The vilification of me out here from the large landowners and bankers is pretty bad. The latest is a rumor started by them that the Okies hate me and have threatened to kill me for lying about them. I’m frightened at the rolling might of this damned thing. It is completely out of hand; I mean a kind of hysteria about the book is growing that is not healthy.”[31]

The then First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, already a fan of Steinbeck’s work from Of Mice and Men, defended Steinbeck’s work in her nationally syndicated newspaper column, “My Day”. She wrote: “Now I must tell you that I have just finished a book which is an unforgettable experience in reading. The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, both repels and attracts you. The horrors of the picture, so well drawn, make you dread sometimes to begin the next chapter, and yet you cannot lay the book down or even skip a page.”[32] After visiting California labor camps in 1940, a reporter asked her if she believed that The Grapes of Wrath was exaggerated. Roosevelt responded, “I have never believed that The Grapes of Wrath was exaggerated”.[33]

Nobel Prize

Main article: 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature

In 1962, Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature for his “realistic and imaginative writing, combining as it does sympathetic humor and keen social perception”. The selection was heavily criticized, and described as “one of the Academy’s biggest mistakes” in one Swedish newspaper.[47] The reaction of American literary critics was also harsh. The New York Times asked why the Nobel committee gave the award to an author whose “limited talent is, in his best books, watered down by tenth-rate philosophising”, noting that “[T]he international character of the award and the weight attached to it raise questions about the mechanics of selection and how close the Nobel committee is to the main currents of American writing. … [W]e think it interesting that the laurel was not awarded to a writer … whose significance, influence and sheer body of work had already made a more profound impression on the literature of our age”.[47] Steinbeck, when asked on the day of the announcement if he deserved the Nobel, replied: “Frankly, no.”[17][47] Biographer Jackson Benson notes, “[T]his honor was one of the few in the world that one could not buy nor gain by political maneuver. It was precisely because the committee made its judgment … on its own criteria, rather than plugging into ‘the main currents of American writing’ as defined by the critical establishment, that the award had value.”[17][47] In his acceptance speech later in the year in Stockholm, he said:

the writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man’s proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit—for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion and love. In the endless war against weakness and despair, these are the bright rally flags of hope and of emulation. I hold that a writer who does not believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature.

— Steinbeck Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech[48]

Fifty years later, in 2012, the Nobel Prize opened its archives and it was revealed that Steinbeck was a “compromise choice” among a shortlist consisting of Steinbeck, British authors Robert Graves and Lawrence Durrell, French dramatist Jean Anouilh and Danish author Karen Blixen.[47] The declassified documents showed that he was chosen as the best of a bad lot.[47] “There aren’t any obvious candidates for the Nobel prize and the prize committee is in an unenviable situation,” wrote committee member Henry Olsson.[47] Although the committee believed Steinbeck’s best work was behind him by 1962, committee member Anders Österling believed the release of his novel The Winter of Our Discontent showed that “after some signs of slowing down in recent years, [Steinbeck has] regained his position as a social truth-teller [and is an] authentic realist fully equal to his predecessors Sinclair Lewis and Ernest Hemingway.”[47]

Although modest about his own talent as a writer, Steinbeck talked openly of his own admiration of certain writers. In 1953, he wrote that he considered cartoonist Al Capp, creator of the satirical Li’l Abner, “possibly the best writer in the world today”.[49] At his own first Nobel Prize press conference he was asked his favorite authors and works and replied: “Hemingway‘s short stories and nearly everything Faulkner wrote.”[17]

In September 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded Steinbeck the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[50]

In 1967, at the behest of Newsday magazine, Steinbeck went to Vietnam to report on the war. He thought of the Vietnam War as a heroic venture and was considered a hawk for his position on the war. His sons served in Vietnam before his death, and Steinbeck visited one son in the battlefield. At one point he was allowed to man a machine-gun watch position at night at a firebase while his son and other members of his platoon slept.[51]

The Grapes of Wrath

Main article: The Grapes of Wrath

The Grapes of Wrath was published during the Great Depression and had a contemporary setting, describing a family of sharecroppers, the Joads, who were driven from their land by the dust storms of the Dust Bowl. The title is a reference to the Battle Hymn of the Republic. Some critics found it too sympathetic to the workers’ plight and too critical of capitalism,[95] but it found a large audience of its own. It won both the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize for fiction (novels) and was adapted as a film starring Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell and directed by John Ford.