ULA/AA’s appeal for international recognition reflects not just Rakhine nationalism, but a new phase of Myanmar’s disintegration — one that could reshape regional politics from the Bay of Bengal to China’s borders.

By Aung San Oo in Burmese, translated, and added comment by Dr Ko Ko Gyi

(Myanmar Muslims News Network)

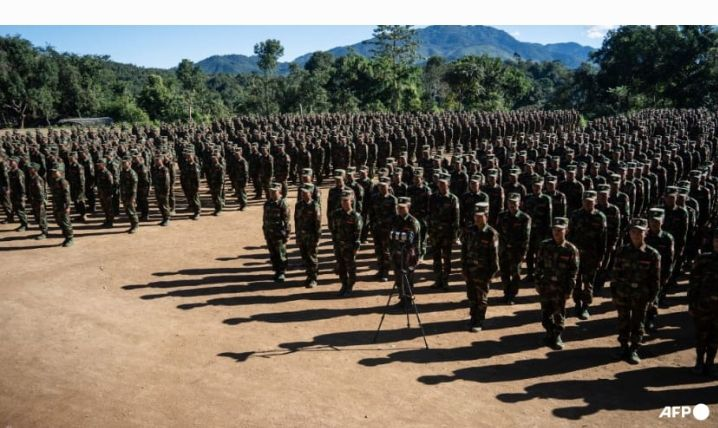

The United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) has transformed from an armed resistance into a functioning local authority, controlling most of Rakhine State. With more than 200 Rakhine civil organizations now appealing to the UN for official recognition of Rakhine as a sovereign state, the struggle has entered a decisive new stage — the shift from rebellion to state-building.

Under the 1933 Montevideo Convention, a state must have a permanent population, defined territory, effective government, and the capacity to engage in foreign relations. The ULA/AA now meets most of these requirements in practice, lacking only the final step — international recognition. This latest move is therefore both symbolic and strategic: an invitation for the world to acknowledge political reality on the ground.

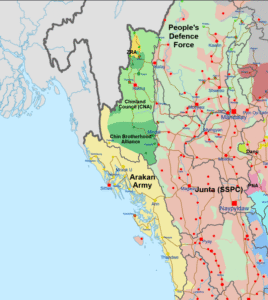

Inside Myanmar, this development challenges the National Unity Government (NUG) and other ethnic forces striving to build a Federal Democratic Union. NUG supports ethnic self-determination, but not secession. A recognized Rakhine state would redefine federal negotiations and potentially inspire similar demands in Chin, Kachin, and other regions. The fragile dream of a united federal Myanmar would face its sternest test.

Neighbouring countries watch closely. Bangladesh fears further refugee inflows and possible border instability. India, with its Kaladan project and vulnerable northeast, prefers stability within a unified Myanmar. China, the most influential external player, will likely act as both broker and gatekeeper — seeking stability that protects its strategic corridors while maintaining leverage over all sides.

Meanwhile, conflict spillovers already reach Chin, Magway, Sagaing, and Ayeyarwady, where local resistance forces are learning from Rakhine’s model of governance. If left unresolved, Myanmar risks evolving into a patchwork of semi-autonomous zones — a Balkanization of the once-unitary state.

For now, the ULA/AA’s “statehood” is de facto, not de jure. Yet it has already altered the balance of power in Myanmar’s west and may soon force diplomats to confront an uncomfortable question: Is Myanmar still one country, or several new ones in the making?