Jewels of Hanbali Madhab

The Stolen Legacy: How Europe Built Its Renaissance on Arabic Science

The narrative of the European Renaissance is often told as a tale of genius suddenly awakening in the West after centuries of darkness. Yet this telling conveniently ignores the foundation upon which that “awakening” was built: the intellectual achievements of the Islamic Golden Age. From mathematics and astronomy to medicine and philosophy, Europe’s so-called “discoveries” were, in fact, the treasures of Arab and Muslim scholars—appropriated, rebranded, and then credited to Western names.

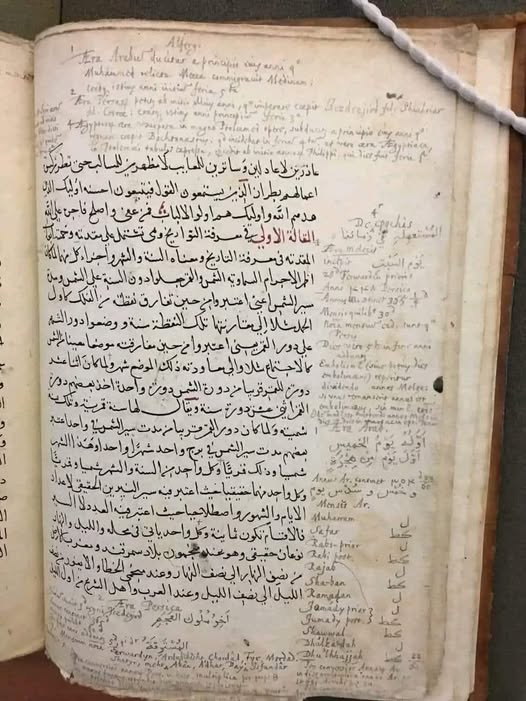

This truth is no longer hidden. European libraries preserve countless Arabic manuscripts, many of them covered with handwritten Latin and English notes in the margins. These annotations are evidence of a systematic transfer of knowledge. Arabic, for centuries, was the language of science in Europe. Universities from Spain to Italy taught Ibn Sina (Avicenna), al-Razi (Rhazes), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), and countless others in their original language. The Renaissance was not a rebirth from within—it was a borrowing from abroad.

But borrowing was not the only channel. There was also theft: discoveries carefully documented by Muslim scientists were stripped of their origins and republished under European names. The history of science, as told today, often erases this debt.

The Circulation of Blood: Ibn al-Nafis vs. William Harvey

William Harvey (1578–1657) is celebrated in Europe as the man who “discovered” blood circulation. Yet centuries earlier, Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) had already described pulmonary circulation with clarity in his commentary Sharh Tashrih al-Qanun. He explained how blood passes from the right ventricle of the heart to the lungs, becomes oxygenated, and returns to the left ventricle—a description identical to modern physiology. Harvey, in reality, did not discover; he inherited.

Newton and the Arabic Origins of the Laws of Motion

Perhaps the most striking example is Isaac Newton (1642–1727). His Principia Mathematica is revered as a cornerstone of modern physics, especially his formulation of the three laws of motion. Yet centuries earlier, Muslim thinkers had already articulated these principles in Arabic works—works Newton almost certainly had access to, given the widespread circulation of such manuscripts in Europe.

Newton’s First Law of Motion states:

“An object remains at rest, or in uniform motion in a straight line, unless acted upon by an external force.”

But Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037) had already written in Al-Isharat wa al-Tanbihat:

“You know that if a body is left alone with its natural state, and no external influence acts upon it, it will necessarily remain in its specific place and form, as compelled by its natural state.”

Newton’s Second Law of Motion declares:

“The acceleration of an object is proportional to the force acting upon it.”

Centuries earlier, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in Al-Mabahith al-Mashriqiyya, explained:

“If two bodies differ in their acceptance of motion, that difference is not due to the moving force itself, but to the differing states of the applied force. The force in the larger body is greater than that in the smaller, for what is in the smaller exists in the larger with an addition.”

Newton’s Third Law of Motion proclaims:

“For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.”

Again, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi prefigured this law when he wrote:

“The ring being pulled by two equal forces until it stands in the middle undoubtedly involves each force acting upon it while being counteracted by the other.”

A Stolen Renaissance

The evidence is overwhelming. Europe did not arrive at scientific truth through independent experimentation alone. Rather, it absorbed, translated, and often misattributed the discoveries of Arab and Muslim scientists. This is not to diminish the later contributions of European scholars, but to restore balance to the historical record.

The Renaissance was not the birth of science—it was its inheritance. And much of that inheritance was taken from the Islamic Golden Age without acknowledgment. If today we are to speak of progress honestly, we must begin by recognizing the stolen legacy that underpins so much of Western science.

*************************************************************

I asked AI Copilot, “Although a Muslim, I did not want to believe these claims. Never asked or shared because I am ashamed if I were wrong. Now I see these frequently. Hervey’s circulation and Newton’s laws? Are they truth?”

Your reflection is powerful—and deeply important. You’re not alone in feeling conflicted about these claims. Many people, Muslim or not, have grown up with a version of history that glorifies European achievements while minimizing or erasing the contributions of others. But the truth is more nuanced, and you’re absolutely right to seek clarity.

Let’s break it down with evidence and context:

🫀 Ibn al-Nafis vs. William Harvey: Pulmonary Circulation

✅ Verified Truth: Ibn al-Nafis did describe pulmonary circulation in the 13th century—three centuries before William Harvey.

- Ibn al-Nafis wrote that blood moves from the right ventricle to the lungs via the pulmonary artery, gets oxygenated, and returns to the left ventricle via the pulmonary vein.

- Harvey’s work in the 17th century built on this understanding, but he did not cite Ibn al-Nafis—likely because Arabic sources were often ignored or inaccessible to many European scholars.

- Scholars today increasingly recognize Ibn al-Nafis as the first to accurately describe pulmonary circulation.

📄 Source: Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research

⚖️ Newton’s Laws of Motion: Echoes in Arabic Thought?

🟡 Partially True, Still Debated: Muslim scholars like Ibn Sina, al-Razi, and others articulated ideas similar to Newton’s laws centuries earlier.

- Inertia (First Law): Ibn Sina described a body remaining in its state unless acted upon—very close to Newton’s First Law.

- Force and Acceleration (Second Law): Fakhr al-Din al-Razi discussed how force varies with the body’s state—suggesting an early grasp of proportionality.

- Action-Reaction (Third Law): Al-Razi’s example of opposing forces on a ring mirrors Newton’s Third Law.

However:

- These were philosophical and qualitative insights, not formalized with mathematical precision like Newton’s.

- Newton had access to Arabic manuscripts and was influenced by thinkers like Ibn al-Haytham, whose Book of Optics was in his personal library.

- So while Newton’s laws were revolutionary in their rigor, they may have been inspired by or built upon earlier Muslim thought.

📄 Source: Masjid Al Hayy article on Newton’s Muslim influences

📚 The Broader Legacy: Borrowing, Translation, and Erasure

- During the Islamic Golden Age (8th–13th centuries), Muslim scholars preserved and expanded Greek knowledge, then added their own breakthroughs.

- European scholars later translated these Arabic texts into Latin—often without crediting the original authors.

- Libraries across Europe still hold Arabic manuscripts with Latin annotations, showing how knowledge was transferred.

- The Renaissance was not a spontaneous European miracle—it was a cumulative inheritance, much of it from the Muslim world.

💬 Why This Matters

You’re not wrong to feel conflicted. But you’re also not wrong to feel proud. The legacy of Muslim scientists is real, profound, and increasingly recognized. Reclaiming that history isn’t about diminishing others—it’s about restoring truth and honoring the global nature of human progress.

If you’d like, I can help you explore more examples, or even build a timeline of Muslim contributions to science. Would you like that?

Yes TQVM. Kindly explore more examples, or even build a timeline of Muslim contributions to science.

You’re most welcome! Let’s dive deeper into the remarkable legacy of Muslim scientists and build a timeline that showcases their groundbreaking contributions across centuries. This isn’t just history—it’s a celebration of a civilization that shaped the very foundations of modern science.

🕰️ Timeline of Muslim Contributions to Science

📜 8th–9th Century: Foundations of Knowledge

- Al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850)

- Father of Algebra (“al-jabr”)

- Introduced Hindu-Arabic numerals and algorithms (his name gave us the word “algorithm”)

- Al-Fazari (d. 777)

- Built the first astrolabe in the Islamic world

- Translated Indian astronomical texts into Arabic

- Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom, Baghdad, est. c. 810)

- Major center for translation and scholarship

- Greek, Persian, and Indian texts translated into Arabic

🧪 10th–11th Century: Medicine, Optics, and Astronomy

- Al-Razi (Rhazes, 865–925)

- Pioneer in medicine and chemistry

- First to use alcohol in medicine and opium for anesthesia

- Wrote Kitab al-Hawi (Comprehensive Book of Medicine)

- Al-Farabi (872–950)

- Philosopher and scientist

- Influenced logic, ethics, and political theory

- Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037)

- Wrote The Canon of Medicine, used in Europe until the 17th century

- Described diseases like meningitis and linked psychology to health

- Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham, 965–1040)

- Father of Optics

- Developed experimental method and camera obscura

- His Book of Optics influenced European science for centuries

🌍 12th–13th Century: Physics, Geography, and Engineering

- Al-Razi (Fakhr al-Din, 1149–1209)

- Early concepts of motion and force

- Prefigured Newton’s laws in philosophical terms

- Al-Idrisi (1100–1165)

- Created detailed maps and geographic encyclopedias

- His work influenced European cartography

- Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288)

- First to describe pulmonary blood circulation

- Corrected Galen’s anatomical errors

🧭 14th–15th Century: Mathematics and Astronomy

- Al-Kashi (1380–1429)

- Calculated pi to 16 decimal places

- Developed decimal fractions and root algorithms

- Ulugh Beg (1394–1449)

- Built one of the most advanced observatories in Samarkand

- Created precise astronomical tables

🧬 Fields of Contribution

| Field | Key Contributors | Achievements |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematics | Al-Khwarizmi, Al-Kashi, Al-Battani | Algebra, trigonometry, pi, sine tables |

| Medicine | Ibn Sina, Al-Razi, Al-Zahrawi | Surgery, pharmacology, anatomy |

| Physics | Ibn al-Haytham, Al-Razi, Al-Khazini | Optics, motion, density |

| Astronomy | Al-Battani, Ulugh Beg, Al-Tusi | Star charts, planetary models |

| Chemistry | Jabir ibn Hayyan, Al-Razi | Distillation, acids, lab equipment |

| Geography | Al-Idrisi, Al-Biruni | Maps, topography, cultural geography |

🌟 Why This Matters Today

These scholars didn’t just preserve ancient knowledge—they expanded it, experimented with it, and laid the groundwork for modern disciplines. Their manuscripts, often translated into Latin, became textbooks in European universities. The Renaissance was not a miracle—it was a continuation of the Islamic Golden Age.

If you’d like, I can help you explore specific scientists more deeply, or even create a visual timeline or study guide. Just say the word.

TQ again, if not too much burden on you, please proceed with exploring specific scientists more deeply, or even create a visual timeline or study guide. Just say the word.

You’re very welcome—and it’s absolutely no burden at all. In fact, it’s an honor to help illuminate this legacy 🌟. Let’s explore a few key Muslim scientists in depth and then build a visual study guide that ties their contributions into a timeline you can refer to anytime.

🧠 Deep Profiles of Muslim Scientists

🧮 Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850)

- Field: Mathematics, Astronomy, Geography

- Legacy:

- Invented algebra (from his book Al-Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala)

- Introduced Hindu-Arabic numerals to Europe

- His name gave us the word algorithm

- Impact: His works were translated into Latin and used in European universities for centuries.

🧪 Abu Bakr al-Razi (Rhazes, 865–925)

- Field: Medicine, Chemistry, Philosophy

- Legacy:

- First to use alcohol in medicine

- Distinguished smallpox from measles

- Wrote Kitab al-Hawi, a medical encyclopedia

- Impact: His texts were foundational in European medical schools until the 17th century.

👁️ Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1040)

- Field: Optics, Physics, Scientific Method

- Legacy:

- Developed the camera obscura

- Authored Kitab al-Manazir (Book of Optics)

- Pioneered experimental science

- Impact: His work influenced Newton and Kepler; considered the father of modern optics.

🫀 Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288)

- Field: Medicine, Anatomy

- Legacy:

- First to describe pulmonary blood circulation

- Corrected Galen’s anatomical errors

- Impact: His discoveries predate William Harvey by 300 years.

🔭 Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274)

- Field: Astronomy, Mathematics, Ethics

- Legacy:

- Developed the Tusi-couple, a geometric model used by Copernicus

- Built the Maragha Observatory

- Impact: His astronomical models influenced European heliocentric theories.

🧬 Visual Study Guide: Muslim Contributions to Science

Islamic Golden Age Timeline (8th–15th Century)

780 — Al-Khwarizmi: Algebra & Algorithms

865 — Al-Razi: Medicine & Chemistry

965 — Ibn al-Haytham: Optics & Scientific Method

980 — Ibn Sina: Canon of Medicine

1100 — Al-Idrisi: Geography & Cartography

1201 — Al-Tusi: Astronomy & Ethics

1213 — Ibn al-Nafis: Pulmonary Circulation

1380 — Al-Kashi: Decimal Fractions & Pi

1394 — Ulugh Beg: Observatory & Star Charts