The Rohingya Expulsion and the Military’s Land Grab

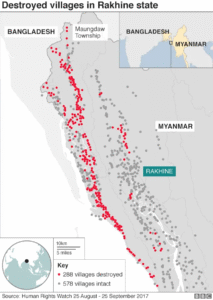

The expulsion of the Rohingya from northern Rakhine did not simply produce a humanitarian catastrophe; it also created a vast landscape of abandoned villages and fertile lands. These territories, once inhabited and cultivated by entire communities, have become strategic assets for Myanmar’s military authorities and their business partners. In many areas, land values have risen sharply due to large-scale infrastructure and resource projects financed by China and other foreign investors.

The government has already announced that it will take control of “fire-damaged” land in Rakhine State for purposes of “redevelopment.” Crucially, no details have been given about restitution for the rightful owners, nor about the governance mechanisms to ensure local communities will benefit. This creates a legal and moral vacuum in which confiscation is disguised as redevelopment.

Chinese Projects and Local Exclusion

Massive Chinese-financed projects — ports, pipelines, special economic zones — have been pushed through Rakhine and beyond. Local populations have consistently raised concerns: not only about displacement and environmental damage, but also about being excluded from the economic benefits. The majority of skilled and semi-skilled jobs have been filled by imported Chinese personnel, leaving Myanmar’s own people sidelined.

The Kofi Annan-led Advisory Commission on Rakhine State already warned in its 2017 report that unless local communities saw tangible benefits, foreign investment would only deepen resentment and instability. To date, however, profits have largely flowed into Naypyidaw and foreign corporations, with little or nothing returned to the communities most affected.

A Pattern of Illicit Confiscation

The pattern extends beyond Rakhine. Across Myanmar, the junta has confiscated properties from political opponents, Civil Disobedience Movement participants, and members of the Summer Revolution. The recent auctioning of NLD leader Win Mya Mya’s shop-lot in Mandalay is one such example. These properties, like the lands of the Rohingya and Kaman, represent illicitly seized assets obtained through coercion, intimidation, and persecution.

For this reason, these confiscated lands and properties must be recognized internationally as BLOOD LAND — akin to “blood diamonds” in Africa or illegally logged rainforest timber. They are tainted assets, produced through systematic human rights violations, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

Why “BLOOD LAND” Matters in International Law

International human rights law, international humanitarian law, and customary norms governing property rights in conflict zones all point in one direction: land obtained through ethnic cleansing, persecution, or political repression cannot be legitimized by auction or redevelopment.

- Geneva Conventions (IV, 1949) prohibit the seizure and destruction of civilian property in occupied or conflict-affected territories.

- The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court treats forcible transfer of populations, persecution, and appropriation of property as crimes against humanity.

- The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights obligate companies and investors to avoid benefiting from land acquired through gross human rights abuses.

The notion of “BLOOD LAND” therefore serves not only as moral language, but as a legal framework for accountability. Just as the Kimberley Process was established to regulate and stigmatize blood diamonds, international mechanisms must now stigmatize and block transactions linked to Myanmar’s BLOOD LAND.

Policy Demands for International Actors

To ensure that dispossession is not rewarded, we call upon international governments, NGOs, and investors to:

- Catalogue and Publicize: Support independent initiatives to map and register all confiscated properties in Myanmar, including those of the Rohingya, Kaman, and pro-democracy activists.

- Boycott and Sanction: Refuse to buy products, timber, minerals, or real estate linked to BLOOD LAND. Pressure corporations and investors to disclose supply chains and land acquisitions.

- Condition Aid and Investment: Tie all development aid, loans, and investment approvals to transparent land restitution mechanisms and local benefit-sharing.

- Support Justice Mechanisms: Provide evidence and resources to ongoing international investigations into Myanmar’s crimes, including before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC).

- Apply Precedent: Extend lessons from the “blood diamonds” framework to create an international regulatory regime addressing BLOOD LAND, preventing its laundering into “legitimate” commerce.

Conclusion: No Legitimacy Without Restitution

Every acre of land confiscated from Rohingya families, Kaman communities, or democracy activists represents not only material dispossession but also a violation of international law. Treating such land as a commercial asset legitimizes ethnic cleansing and authoritarian plunder.

The international community has a choice: either normalize BLOOD LAND as just another commodity, or confront it for what it is — stolen property tainted by blood. Like blood diamonds and illegally logged rainforests, BLOOD LAND must be stigmatized, boycotted, and legally challenged until restitution and justice are delivered.