Credit translated and edited from U Aun Tin’s FB post on 21st. September 2016

For decades, Myanmar’s rulers have claimed that the country is home to exactly “135 national races.” This number is repeated in official speeches, textbooks, and government documents. But where did it come from? Why was it chosen? And why has the figure changed several times over the last half-century?

A Questionable Invention

Contrary to what people are led to believe, there has never been a transparent, nationwide consultation or parliamentary debate that produced the number 135. No historical records from the Pagan, Konbaung, or even British colonial eras mention such a figure. In fact, before independence, only the major ethnic groups—Bamar, Karen, Shan, Chin, Kachin, Mon, Rakhine—along with occasional references to Chinese, Indian, Pyu, Talaing, Pathi (Muslims), and others, were documented.

The British censuses of 1911 and 1931 recorded 65 and 135 languages respectively, but not “135 races.” This appears to be the earliest root of the figure, but even then it referred to languages, not ethnic identities.

After independence, successive governments—AFPFL, caretaker, parliamentary, and even early BSPP under Ne Win—never endorsed the number 135.

The first official ethnic list only appeared in December 1972, when the Ministry of Home and Religious Affairs published a list of 144 groups. That list included Burmese Muslims (Pathi), Rohingya, Myedu, Pashu (Malays), and Panthay.

Curiously, both 144 and 135 add up numerologically to nine (1+4+4=9; 1+3+5=9), leading some to suspect that numerology, not ethnography, guided these decisions.

From 144 to 135—and Then to 101

During the 1980s, the number was quietly reduced. Several Muslim groups were deleted, while the Kokang Chinese were added.

In July 1989, Senior General Saw Maung officially announced “135 races” in a martial law speech. In truth, these should more accurately be called “martial law races” rather than national races.

Later still, under U Thein Sein’s government, a new list of 101 races mysteriously appeared. The Election Commission even used this figure to reject the Zo-Mi National Congress Party, saying the Zo-Mi were not included. After protests, Zo-Mi were accepted as a national race—yet the total remained at 101. That implied another group had been silently removed.

So Myanmar’s ethnic count has jumped from 144 → 135 → 101 → back to 135, without explanation or public accountability.

Flaws and Manipulations in the 135 List

Even within the current list of 135, major flaws and inconsistencies abound:

- Kachin: Realistically 6 groups, but split into 12.

- Kayah: 5 groups inflated into 9.

- Karen: 3 main groups (Sgaw, Pwo, Bwe) expanded into 11.

- Chin: Despite over 500 clans, only 53 were recognized.

- Bamar: Subgroups like Yaw, Tavoyan, and Beik were forcibly separated, inflating the count.

- Mon: Reduced to just one, while related groups like Wa and Palaung were shifted into Shan.

- Rakhine: Chin-related groups like Khami and Mro wrongly included under Rakhine.

- Shan: Of the 33 listed, only about 21 are genuinely Shan; the rest are Tibetans, Mons, Khmers, or unrelated groups.

If carefully reviewed, Myanmar has barely 60 truly distinct ethnic groups.

Even if historically recognized communities such as Gurkha, Panthay, Pathi (Burmese Muslims), Rohingya, Pashu (Malays), and Myedu are restored, the number would not exceed 70.

A Tool of Exclusion

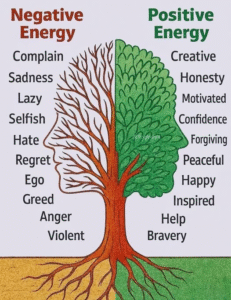

The shifting figures reveal a political tool rather than a scientific classification.

Entire communities have been erased from official recognition—particularly Muslims such as Rohingya, Pathi, and Panthay—while others were artificially split to inflate the count.

Ethnic identities in Myanmar were never meant to be decided behind closed doors by generals or election commissioners. Yet that is precisely what has happened, with no public debate, no accountability, and no transparency.

Conclusion

The “135 races” claim is a manufactured myth. It is neither rooted in history nor in genuine ethnographic research. Instead, it has been used to divide, exclude, and manipulate.

Myanmar’s true ethnic diversity deserves honest recognition, not political arithmetic. Any future democratic government must begin with transparent, inclusive dialogue on what truly constitutes a “national race.”

ပသီဖိုရမ် – Pathi Forum ·

၁၉၈၂ခုနှစ်နိုင်ငံသားဥပဒေ တိုင်းရင်းသားလူမျိုး

(၁၄၄)မျိုးအတည်ဖြစ်လျှက်ရှိပါတယ်။၁၃၅မျိုးဆိုတာတရားဝင်ကြေညာခြင်းမရှိပါ။

၁၉၈၂ ခုနှစ်နိုင်ငံသားဥပဒေတွင် တိုင်းရင်းသားလူမျိုးအရေအတွက်ကို တရားဝင် ၁၄၄ မျိုးအဖြစ် သတ်မှတ်ထားပြီး၊ လူထုအတွင်း အများအားဖြင့် ပြောဆိုနေကြသည့် “၁၃၅ မျိုး” ဆိုသည့် အရေအတွက်ကို တရားဝင်ကြေညာချက်အဖြစ် မရှိပါ။ ဤအချက်သည် မြန်မာနိုင်ငံသားအခွင့်အရေး၊ လူမျိုးစဉ်ဆက်အမည်များနှင့် နိုင်ငံရေးအလယ်အလတ်တွင် အရေးကြီးသော အငြင်းပွားမှုတစ်ခုဖြစ်နေသည်။

၁၉၈၂ ခုနှစ်နိုင်ငံသားဥပဒေ၏ အကျိုးသက်ရောက်မှု

– ဥပဒေ၏အခြေခံအချက်

၁၉၈၂ ခုနှစ်နိုင်ငံသားဥပဒေသည် “နိုင်ငံသား” အဖြစ် သတ်မှတ်ရန် အခြေခံအချက်ကို တိုင်းရင်းသားလူမျိုး (National Races) အဖြစ် သတ်မှတ်ထားသည်။

ဥပဒေတွင် ၁၈၂၄ ခုနှစ် (ဗြိတိသျှ အင်္ဂလိပ်တို့ ပထမဆုံး အကျွံ့ဝင်သည့်နှစ်) မတိုင်မီ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတွင် နေထိုင်ခဲ့ကြသူများကို “တိုင်းရင်းသား” အဖြစ် သတ်မှတ်သည်။

– ၁၄၄ မျိုး vs ၁၃၅ မျိုး

တရားဝင်စာတမ်းများတွင် ၁၄၄ မျိုး အဖြစ် အတည်ပြုထားသော်လည်း၊ နိုင်ငံရေး၊ လူမှုရေး အလယ်အလတ်တွင် ၁၃၅ မျိုး ဟူ၍ အများအားဖြင့် ပြောဆိုနေကြသည်။

ဤ “၁၃၅” ဆိုသည့် အရေအတွက်သည် တရားဝင်မဟုတ်သော်လည်း စာတမ်းများ၊ အစိုးရအဆင့်အတန်းများတွင် အချို့အသုံးပြုနေကြသည်။

—

အဓိက အငြင်းပွားမှုများ

– လူမျိုးစဉ်ဆက်အမည်များ

တိုင်းရင်းသားအမည်များကို အစိုးရက သတ်မှတ်ပုံသည် အများအားဖြင့် အမည်များကို ခွဲခြားထားခြင်း ဖြစ်ပြီး၊ တူညီသော လူမျိုးများကို အမျိုးစုံအဖြစ် သတ်မှတ်ထားသည်။

ဥပမာ – ကချင်၊ ရှမ်း၊ ချင်းတို့တွင် အမျိုးစုံခွဲခြားထားသည့်အတွက် အရေအတွက်များလာသည်။

– အခွင့်အရေးများ

ဥပဒေသည် နိုင်ငံသားအခွင့်အရေးကို လူမျိုးအပေါ် မူတည်သတ်မှတ်ထားခြင်း ဖြစ်သဖြင့်၊ တရားဝင် သတ်မှတ်မခံရသော လူမျိုးများ (ဥပမာ – ရိုဟင်ဂျာ) ကို နိုင်ငံသားအဖြစ် မခံယူနိုင်စေခဲ့သည်။

ဤအချက်သည် လူ့အခွင့်အရေး အဖွဲ့အစည်းများ၊ အပြည်ပြည်ဆိုင်ရာ အဖွဲ့များမှ အလွန်အကျိုးသက်ရောက်မှုရှိသည့် အားနည်းချက် အဖြစ် သတ်မှတ်ထားသည်။

—

အကျိုးဆက်များ

– နိုင်ငံရေးအကျိုးဆက်

တိုင်းရင်းသားအရေအတွက်ကို တရားဝင်မဟုတ်သည့် “၁၃၅” အဖြစ် အသုံးပြုခြင်းသည် နိုင်ငံရေးအလယ်အလတ်တွင် အမှားအယွင်းများ၊ အငြင်းပွားမှုများ ဖြစ်စေသည်။

– လူမှုရေးအကျိုးဆက်

တိုင်းရင်းသားအမည်များကို ခွဲခြားသတ်မှတ်ထားခြင်းကြောင့် လူမျိုးစဉ်ဆက်များအကြား အနာဂတ်အခွင့်အရေးများ၊ လူမှုရေးအညစ်အကြေးများ ဖြစ်စေသည်။

– အပြည်ပြည်ဆိုင်ရာအကျိုးဆက်

၁၉၈၂ ဥပဒေသည် အပြည်ပြည်ဆိုင်ရာ လူ့အခွင့်အရေး စံချိန်စံညွှန်းများနှင့် မကိုက်ညီခြင်း အဖြစ် အများကြီး ဝေဖန်ခံရသည်။

၁၉၈၂ ခုနှစ်နိုင်ငံသားဥပဒေသည် တိုင်းရင်းသားအရေအတွက်ကို တရားဝင် ၁၄၄ မျိုးအဖြစ် သတ်မှတ်ထားပြီး၊ “၁၃၅ မျိုး” ဆိုသည့် အရေအတွက်သည် တရားဝင်မဟုတ်ပါ။ ဤအချက်သည် မြန်မာနိုင်ငံသားအခွင့်အရေး၊ လူမျိုးစဉ်ဆက်အမည်များနှင့် နိုင်ငံရေးအလယ်အလတ်တွင် အရေးကြီးသော အငြင်းပွားမှုတစ်ခုဖြစ်နေသည်။