“Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

The movement of people across frontiers is as old as humanity itself. Before borders were drawn on maps, the world was divided only by natural barriers—rivers, mountains, forests. As some human rights advocates often remind us:

“When God created the world, there were no borders. Man later built them.”

Migration is an instinct as much as it is a necessity. People have always moved in search of cleaner water and greener land. Even jungle trekkers and scouts are taught:

“If lost in the jungle, find a stream and follow it downstream—you’ll eventually reach a settlement.”

This wisdom holds true across centuries of migration into and through Burma (Myanmar), especially from neighboring China and India. Famines in southern China and northern India—well into the 20th century—drove thousands to move. In modern times, while Indian migration into Myanmar diminished after General Ne Win’s 1962 military coup, Chinese migration surged, especially in the north.

And today, ironically, it is the Myanmar people who are desperate to get out—fleeing civil war, economic collapse, and military repression since the 2021 Spring Revolution.

The following is an exploration of the major highways, forgotten caravan trails, and hidden “rat lanes” that have shaped human movement through Burma—past and present.

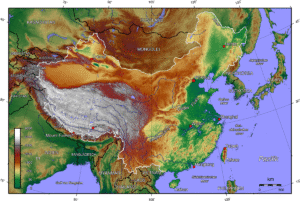

1. Diphu Pass – An Ancient Gateway to the East

Source: Wikipedia work based on Abhijitsathe – Derivative of File:India Arunachal Pradesh location map.svg

Situated near the tri-junction of India, China, and Myanmar, Diphu Pass is one of the northernmost crossings between the countries. Located roughly 30 km east of Dong in Arunachal Pradesh, it has historically served as a military route, trade corridor, and migration path into the eastern Assam hills and northern Myanmar.

Until recently, border tribes could freely cross under the Free Movement Regime (FMR), allowing visa-free travel up to 16 km across the India–Myanmar border. However, in February 2024, India revoked the FMR in response to the Manipur ethnic violence and rising illegal trafficking, effectively closing one more historical route of transborder connection.

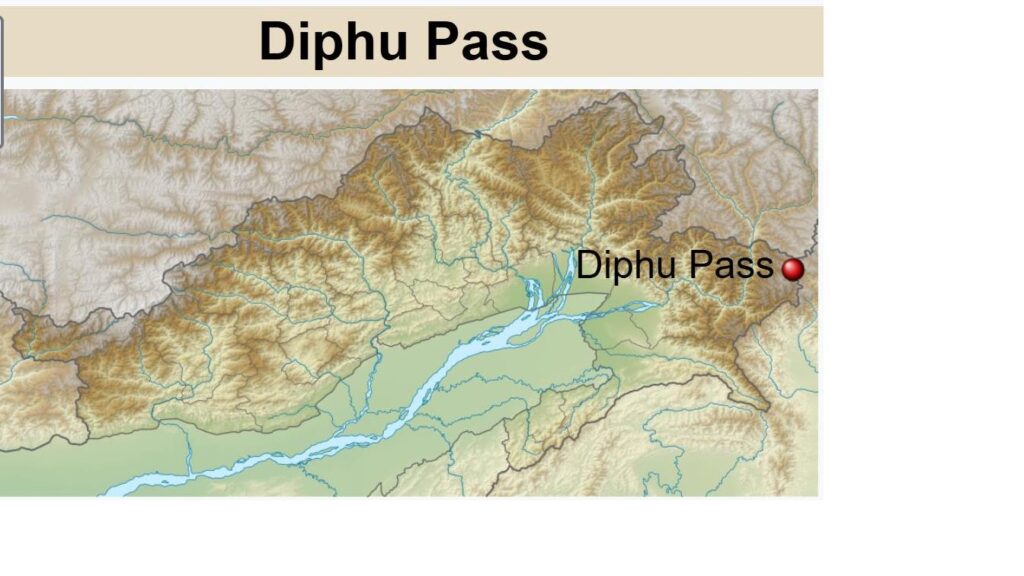

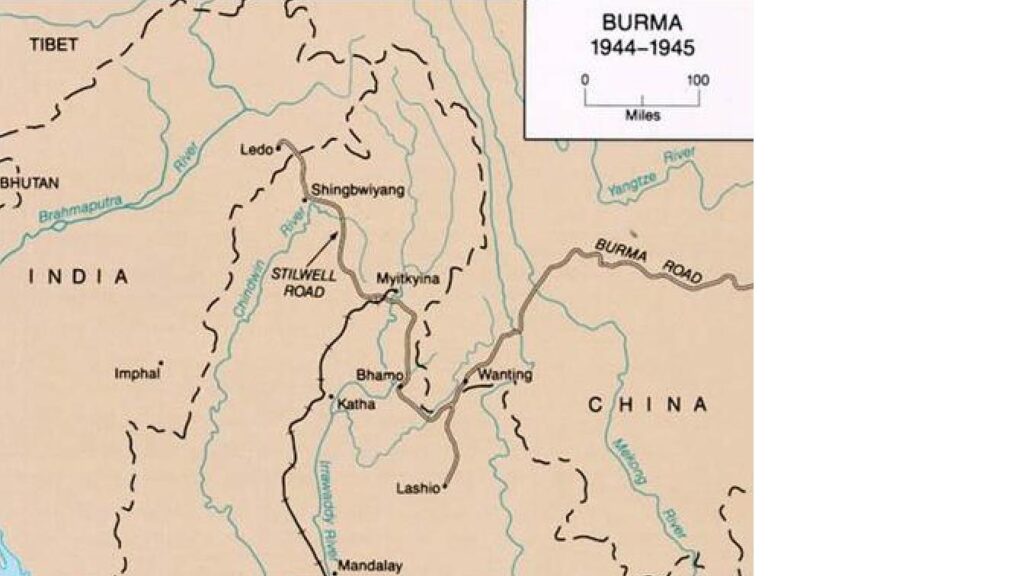

2. Ledo–Myitkyina–Kunming: Stilwell Road and the Wartime Lifeline

Credit Wikipedia, U.S. Army Center of Military History – India-Burma 2 April 1942-28 January 1945, U.S. Army Center of Military History. Burma and Ledo Road 1944 – 1945

Perhaps the most dramatic route of all is the Ledo Road, renamed the Stilwell Road during World War II in honor of U.S. General Joseph Stilwell. This overland supply route was built by Allied forces after the Japanese seized the Burma Road in 1942, cutting off Chinese resistance from its supply lines.

- Length: 1,726 km

- India: 61 km

- Burma: 1,033 km

- China: 632 km

- Route:

Ledo – Pangsau Pass – Tanai – Myitkyina – Bhamo – Namhkam – Kunming

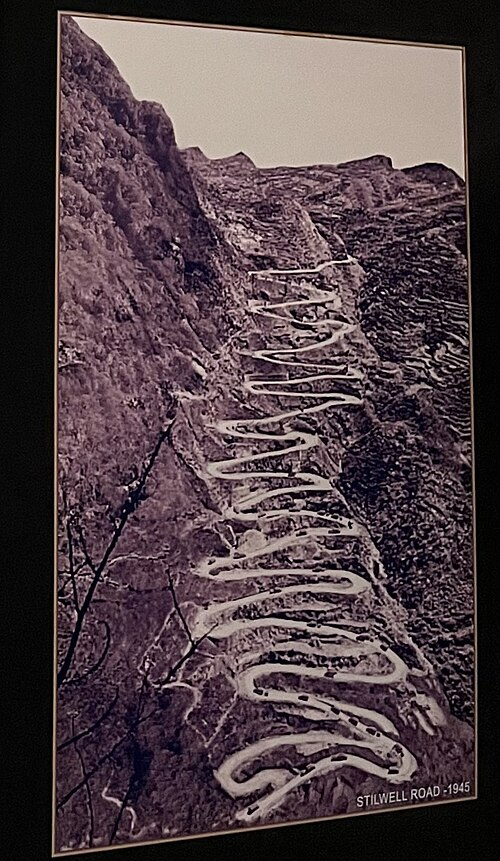

The route traverses the Hukawng Valley and follows paths originally surveyed by British railway engineers in the 19th century. When completed in 1945, it served not only as a military highway but also a symbol of transnational unity and endurance.

Credit. Wikipedia Image of Stilwell Road displayed in Coal Heritage Park & Museum, Margherita, Assam.

Today, China seeks to revive this route as part of its Belt and Road Initiative—linking Kunming to Mandalay and beyond—bringing new economic promise, but also strategic concern.

3. Moreh–Tamu–Mandalay: The Trilateral Highway Corridor

On Myanmar’s western border with Manipur, the town of Moreh connects to Tamu in Myanmar via a well-established overland route, now part of the India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway. This corridor reaches deep into central Burma, providing trade access to Mandalay and beyond.

- Behiang–Khenman in Manipur is another key route, connecting India to Tedim in Chin State—used by locals and traders, as well as refugees during times of unrest.

These roads are not just economic arteries; they are lifelines for ethnic communities divided by borders, including Nagas, Kukis, and Chins, whose shared culture transcends political boundaries.

4. Mizoram Routes and the Kaladan Multi-Modal Corridor

Further south, Mizoram is becoming increasingly connected to Myanmar through infrastructure megaprojects:

- Zochawchhuah–Zorinpui is part of the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, which links Kolkata Port to Sittwe Port (Akyab) in Myanmar, and from there, by river and road to Mizoram’s Lawngtlai district.

- Zokhawthar–Rikhawdar, a frequently used local crossing, is informally used by border communities over the Harhva River bridge.

This network connects the landlocked northeast of India to the sea, enhancing economic integration and allowing strategic bypass of the Siliguri Corridor. It also reconnects people who were historically united by shared migration patterns and trade.

5. Caravans, Conquests, and Colonial Tragedies

Centuries before highways or national flags, the Panthays—Chinese Muslims from Yunnan—emerged as master caravaneers. By the mid-19th century, they controlled an immense trade network from eastern Tibet through Assam, Burma, Thailand, Laos, and even into Vietnam. They were the lifeblood of trans-Himalayan trade, operating deep into the Burmese uplands.

But these same trails were later followed by Burmese military campaigns, turning pathways of commerce into corridors of conquest.

In Assam

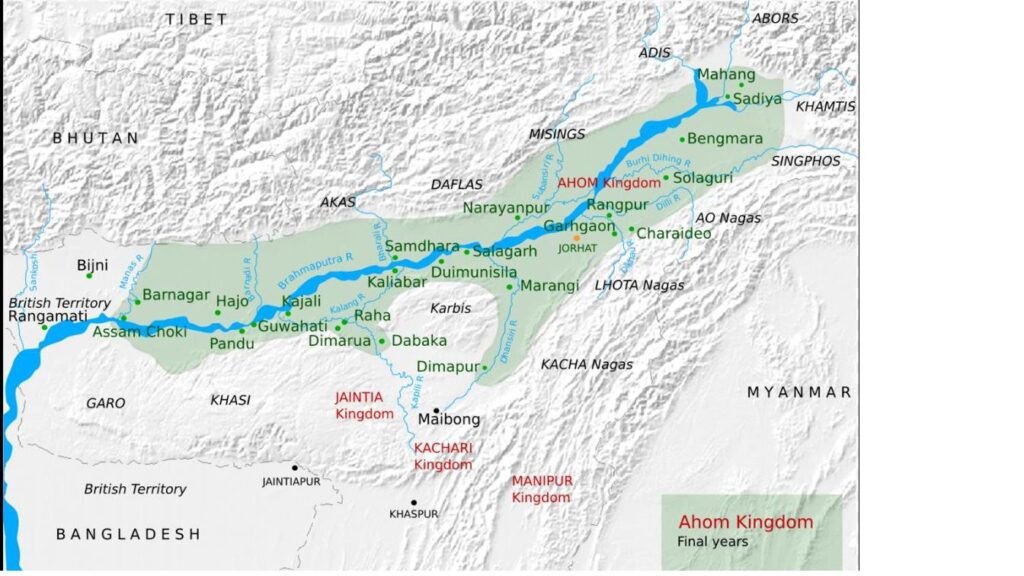

Credit: Wikipedia Chaipau – self-made, based on Fig 1.1 “Ahom Kingdom – 1826” of Taher, M (2001) Bhagawati, A K , ed. Geography of Assam, New Delhi: Rajesh Publications, pp. 1−17 Base map template: demis.nl

Eyewitness Maniram Dewan, writing in Buranji-vivek-ratna, described Burmese atrocities during the invasion of Assam:

“Some they flayed alive. Others they burnt in oil. Beautiful women were unsafe in public. Prayer houses were torched with people inside. Brahmans were forced to carry pork, beef, and wine.”

Thousands were killed, enslaved, or displaced. The Assamese valleys—once fertile and prosperous—were turned into wastelands.

In Manipur

Between 1819–1826, Manipur experienced the “Chahi Taret Khuntakpa” or “Seven Years of Devastation.” Entire villages were burned. Culture and governance collapsed. The Pangal Muslims were enslaved, while others fled into India or were forcibly relocated.

In Arakan (Rakhine)

The invasions led to mass depopulation. Fields around Tavoy (Dawei) were described as “white with human bones.” Tens of thousands of Rakhine Buddhists fled to British-controlled Bengal. A contemporary British report noted:

“In British territory, a man could go to bed at night without wondering whether his throat would be cut by order of an official.”

In Siam (Thailand)

The raids of Bodawpaya and his predecessors left parts of Siam in ruins. Farmlands were abandoned. Civilian massacres and forced relocations became common. These were not religious wars, as most victims were fellow Buddhists, but imperial conquests that devastated entire civilizations.

Modern Border Controls: Fences Instead of Footpaths

In 2003, India began constructing a 1,624-km fence along its border with Myanmar, aiming to curtail:

- Insurgency

- Drug and arms trafficking

- Black market trade

- Illegal migration

This has disrupted centuries-old ethnic and commercial ties. Yet, in remote areas, rat lanes—informal jungle trails—still flourish, used by:

- Refugees

- Ethnic armed groups

- Smugglers and traders

- Desperate migrants

On both the China–Myanmar and India–Myanmar borders, shared ethnic identities and survival instincts often outweigh the presence of fences, patrols, or geopolitics.

Conclusion: The Land That Connects—and Divides

Burma’s geography has made it both a bridge and a battleground. Its rivers, mountain passes, and caravan trails have long connected civilizations—from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal, from Yunnan to Bengal.

But these same routes have witnessed trade and tragedy, migration and massacre, unity and division. As walls rise and borders tighten, the ancient logic remains:

Where there is a will, there is a way.

Even when highways are sealed, the people will find the rat lanes—paths of survival, resistance, and hope.