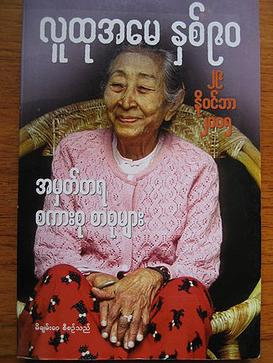

Based on the writings of Ludu Daw Amar, renowned Bamar journalist and cultural historian.

Photo taken by User:Wagaung in Wikipedia

In the heart of old Mandalay, where cultures, faiths, and traditions lived side by side, there once stood a legendary porcelain shop. The soul of that shop was not the owner whose name adorned the signboard — Fwar Zulananji — but a humble, eloquent, and deeply respected woman named Daw Mya. She was more than a shopkeeper; she was a symbol of integrity, trust, and harmony in a complex society.

A Portrait of Trade and Tradition

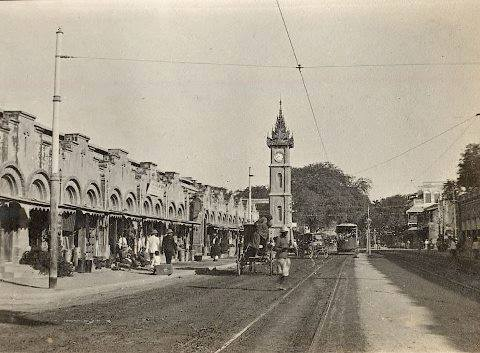

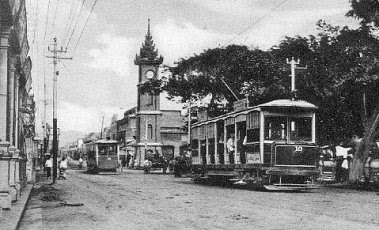

When Ludu Daw Amar recalled her childhood memories of Mandalay, she often described the vivid image of Daw Mya running the largest and busiest porcelain shop in the eastern row buildings of the central market — now known as the City Hall area. The shop spanned three units, numbered 28, 29, and 30. Stacked floor to ceiling with plates, cups, teapots, soup bowls, and spoons — imported from China, Japan, England, and Eastern Europe — the shop catered to both everyday buyers and those purchasing religious donation sets for monks, Kathina ceremonies, and weddings.

Daw Mya stood at the center of it all, single-handedly managing crowds of buyers. With a smile and voice as smooth as a flute, she knew how to deal with everyone — whether it was a monk buying alms bowls, a village woman preparing for a wedding, or a householder needing just a few rice plates.

Even though the business was owned by an Indian man, Daw Mya was the heart of it. Buyers would bypass all other vendors just to speak with her. If she wasn’t present, they would wait. Even when the owner’s son, Bakru Bhai, tried to scold her for giving discounts, she would retort firmly:

“When your people first came to Burma with nothing, it was us Burmese who gave you a hand. I gave a discount because I believed it was right.”

The father, the Indian shop owner, had no choice but to accept it. He knew the shop couldn’t survive without her.

A Muslim, A Mandalay Local, A Burmese

Daw Mya was a Burmese Muslim, and in Mandalay, Muslims are sometimes called Zedabari or Pathi. But these terms were mere labels. In practice, the Muslims of Mandalay had long been considered part of the Bamar cultural fold. They spoke fluent Burmese, followed local customs, and had even been honored during the times of the Burmese monarchy. Many were so thoroughly integrated that their manners and language often exceeded those of native Mandalay Buddhists.

Daw Mya was such a woman — articulate, courteous, and culturally refined. Her skill and charm were so undeniable that even during the anti-Indian riots of 1938, when Buddhist monks and nationalist groups ordered boycotts of Indian-owned shops, an exception was made for Daw Mya’s store. Even the monks continued to buy from her.

A Life of Quiet Struggles

Behind her public strength was a life of quiet personal pain. Daw Mya’s first marriage lasted only four months. Her second husband was abusive, beating her and even throwing her into a fire pit. Unable to endure it, she fled with her young son — who sadly passed away young.

She never remarried. Instead, she raised her niece Khin Ma Ma as her own daughter. For the rest of her life, she lived with dignity, saying:

“Men only bring pain. I don’t even want a male flower vase in my house.”

Her guiding philosophy was simple yet profound:

“The happiest thing in the world is to live with joy. Love everyone. Don’t judge by race or religion.”

A Broker Until the End

Even when she was 90 years old and bedridden from a leg injury, Daw Mya continued to serve her community. People still came to her for advice or to ask for help buying land, houses, or jewelry. She would connect them to trusted brokers and ensure fair deals — all from her bed. According to her great-nephew U Soe Myint, she earned over 20,000 kyats in commission even while bedridden.

During World War II, she had fled Mandalay and taken refuge in Bhone O Village, a well-known Muslim haven. There, she supported herself by working as a broker in gold and gems.

She was born on a Saturday — traditionally associated with fiery temper — but was known for her gentle and forgiving nature. She rarely got angry and always showed patience toward others.

A Beloved Legacy

Daw Mya passed away on August 22, 1972, at the age of 92. To this day, the people of Mandalay remember her not merely as a seller of porcelain but as a woman of grace, fairness, and wisdom.

In the tapestry of Mandalay’s history, Daw Mya stands as a shining thread — a Muslim woman who transcended barriers, who earned the love and trust of all who knew her, regardless of religion or race.

She didn’t just sell goods; she built bridges.

Editor’s Note:

Ludu Daw Amar — a respected Bamar Buddhist journalist and herself a descendant of Thai captives from the Ayutthaya wars — celebrated Daw Mya not as an exception, but as an embodiment of the inclusive spirit of Mandalay. Her words remind us that being Burmese is not confined to religion or bloodline — but is about culture, character, and shared community.

Read also: Ludu Daw Amar praised Myanmar Muslims from Mandalay (in Burmese)

ဆရာမကြိး လူထုဒေါ်အမာရေးသားသော မန္တလေးသူ၊ မန္တလေးသားများစာအုပ်

ကျွန်မတို့ ငယ်ငယ်တုန်းကကြုံရတဲ့ ပန်းကန်သည်ဒေါ်မြကို ဗီဒီယိုရှိတဲ့ခေတ်မျိုး ဆိုရင် ရိုက်ကူးလို့ တောင်ထားပြီး နောက်လူတွေကို ပြချင်ပါရဲ့။ ဟိုခေတ်က ဈေးသည်ဆိုတာ ဒီလိုဟာမျိုးပါလို့။သိန်းပေါင်းများစွာ ရင်းထားတဲ့ ဧရာမဆိုင်ကြီးမှာ ဈေးဝယ်တွေဝိုင်းဝိုင်းလည်နဲ့ ဒေါ်မြ ရောင်းဝယ်နေပုံ ကိုပြစမ်းချင်လို့ပါ။ပန်းကန်ဆိုတာ ဟိုခေတ်က ခုခေတ်ထက် အများကြီးပိုသုံးတဲ့ လူသုံးပစ္စည်းတစ်ခ ုပါ။ ဥပမာတောရွာတွေက ကောက်ပဲသီးနှံပေါ်လို့ အလှူအတန်းပေးကြပြီဆိုရင် ကျွန်မတို့ အညာက တောင်သူ လယ်သမားတေ ွပေးတဲ့အလှူက ငွေကူခံတယ်၊ ငွေကူကို လက်ဖက်ရည်ကြမ်းပန်းကန်နဲ့ ပြန်ပါတယ်။

တောအလှူရဲ့ထုံးစံက အလှူဟာ ထမင်းကျွေးလှူရပါတယ်။ အလှူလာသူက မိမိတတ်အားသလောက် အလှူရှင်ကို ငွေကူပါတယ်။ ကူငွေကိုလိုက်ပြီး အကူပြန်တယ်ရယ်လို့ အလှူရှင်က လက်ဆောင်ပြန်ပေး ပါတယ်။

အဲဒီလက်ဆောင်က ဥပမာ ငွေ ၁ကျပ် ကူတယ်ဆိုရင် လက်ဖက်ရည်ကြမ်းပန်းကန် ၂ လုံး အကူပြန် တယ် ဆိုတာမျိုးလုပ်တာပါ။ ငွေ ၁၀ ကျပ် ကူခဲ့ရင် ပန်းကန်အလုံး ၂၀ ရခဲ့တာပေါ့။

ပြီးတော့ ဘုန်းကြီးလှူတဲ့လှူရန်ပစ္စည်းမှာ ပန်းကန်ခွက်ယောက်က ပါစမြဲ။ ကထိန်ခင်းရင် ကထိန်ပဒေ သာပင်မှာ ပန်းကန်ခွက်ယောက်ပါစမြဲ။ အဲဒါတွေအပြင် အရပ်ထဲမှာ မင်္ဂလာဆောင်တယ်ဆိုရင် မင်္ဂလာ ဆောင်က ရပ်ကွက်လူငယ်မိန်းမငယ်တွေကို ခဲဖိုးပေးတယ်။ အဲဒီခဲဖိုးကို ရှေးကတော့ လူငယ်တွေက သုံးဖြုန်းပစ်တယ်၊ သောက်စားမူးယစ်ပစ်တယ်လို့ မရှိဘူး၊ အရပ်သုံးဘုံပစ္စည်းအဖြစ်နဲ့ အရပ်အလှူအ တန်းမှာ သုံးစွဲဖို့ အိုးအင်ပန်းကန်ခွက်ယောက်ဝယ်ပြီး ရပ်ရွာက လေးစားယုံကြည်တဲ့ လူကြီးတစ်ယောက် ယောက်အိမ်မှာဘုံပစ္စည်းအဖြစ်နဲ့ အပ်နှံထားကြတာပဲ။ ဆွမ်းကျွေးချင်ရင် အဲဒီမှာ အလကားငှား၊ မင်္ဂလာပွဲ ဧည့်ခံချင်ရင်လာငှား၊ ကွဲရင်အစားဝယ်ထည့်ပေးထား၊ လက်ဖက်ရည်အချိုအဖန်နဲ့၊ မုန့်စားပန်ကန်၊ ကာဖီ လက်ဖက်ရည် ပန်းကန်စုံတွေ၊ လင်ပန်းတွေ ငွေတတ်နိုင်သလောက် အရပ်က ဘုံပစ္စည်းအဖြစ် ဝယ်ခြမ်း ထားကြတာပါ။

ဒါကြောင့် ပန်းကန်အသုံးက ခုခေတ်ထက်ပိုများပါတယ်။ အဲဒီလိုရှိရာမှာ ပန်းကန်ဆိုတဲ့ ပစ္စည်းကလည်း တင်သွင်းထားတာက စုံလိုက်တာ။ တရုတ်ပန်းကန်၊ ဂျပန်ပန်းကန်၊ အင်္ဂလန်ပန်းကန်၊ ချက်ကိုစလိုဗက် ကီးယားက ေြွကရည်သုတ်ပစ္စည်း စသဖြင့် နိုင်ငံတကာပစ္စည်းတွေ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံထဲ ဝင်ပြီးရောင်း ချကြတာပါ။

အဲဒီလို ပန်းကန်ရောင်းတဲ့ဆိုင်တွေ မန္တလေးကတိုက်တန်းကြီးနဲ့ တိုက်တန်းကလေး (ခုမြို့တော်ခန်းမ ၂ နေရာ) နဲ့ ဈေးရုံထဲမှာ အများကြီး ရှိကြပါတယ်။ ဒီလိုရှိတဲ့အနက်က အရှေ့ဘက် တိုက်တန်းကြီးပေါ်က သုံးခန်းတွဲပန်းကန်ဆိုင်ကြီးကတော့ အကြီးဆုံးနဲ့ အရောင်းရဆုံးပါပဲ။ ဖွာဇူလာနန်ဂျီ ပန်းကန်ဆိုင်ဆိုပြီး အနီရွှေစာလုံး သစ်သား ဆိုင်ဘုတ်ကြီးကလဲ သုံးခန်းအပြည့်ချိတ်ဆွဲထားတာပါ။

ဆိုင်နံပါတ်က ၂၈၊ ၂၉၊ ၃၀ ထင်တာပဲ။ တိုက်တန်းကြီးသုံးခန်းကို အကန့်တွြေုဖတ်ပြီး ပန်းကန်ဆိုင်ကြီး ခင်း ထားရာမှာ ပန်းကန်တွေ ဆိုတာကတော့ ရာနဲ့ထောင်နဲ့ချီပြီး အထပ်လိုက်အထပ်လိုက်တွေ စီနေတော့တာပါ။ တစ်ဆင်တည်း တစ်သွေးတည်း တစ်ပုံစံတည်း တစ်မျိုးတည်း ရာနဲ့ချီဝယ်မလား၊ ချက်ခြင်းရပါတယ်။ ဇလုံတို့ ဖန်ခွက်တို့ လက်ဖက်ရည်အိုးနဲ့ ပန်းကန်တို့ ဇွန်းခက်ရင်းတို့ ဆိုတာမျိုး တွေကလဲ စုံမှစုံ၊ ဘာမဆို လိုလေသေးမရှိ တည်ခင်းရောင်းချတာပါ။ အဲဒီသုံးခန်းတွဲကြီးမှာ တိုက်တန်းရဲ့ နောက်ဖေးဘက်မှာ သံဆန်ခါတွေကို သေတ္တာလုပ်ပြီး ပန်းကန်တွေထည့်လာတဲ့ သံဆန်ခါ သေတ္တာကြီး တွေကို အလုပ်သမားတွေက ဖောက်တဲ့ သေတ္တာကို ဖောက်ပြီး ဆိုင်ထဲ ပစ္စည်းသစ်ခင်းတယ်။ ဆိုင်ထဲရောင်းရတဲ့ ပန်းကန်ကို ဝယ်သူဆီ တင်ပို့ပေးဖို့ သေတ္တာနဲ့ တောင်းနဲ့ ထုပ်ပိုးပေးတဲ့လူက ပေးတယ်။ ဆိုင်ရှင် ဖွာဇူလာနန်ဂျီဆိုတဲ့ အိန္ဒိယ အမျိုးသားကတော့ ဆိုင်ရဲ့နောက်နား ခပ်ကျကျမှာ စာရေးစာပွဲတစ်လုံးနဲ့ ကုလားထိုင်နဲ့ထိုင်နေတာပါပဲ။

ဆိုင်ရှေ့ဘက်မှာ တကယ်ရောင်းနေသူကတော့ ဒေါ်မြဆိုတဲ့ အမျိုးသမီးကြီးပါ။ ဒီအမျိုးသမီးကြီးက ဒီဆိုင်ကြီးကို လာလာသမျှ ဈေးဝယ်တွေကို တစ်ယောက်တည်း ဒိုင်ခံရောင်းချနေပါတယ်။ တပည့်တွေကတော့ အနားမှာ လက်တိုလက်တောင်းခိုင်းဖို့ ရှိသပေါ့။ ဘယ်သူရေ ဘာယူပြလိုက်စမ်း၊ ဘာကို ထုပ်ပိုးပေးလိုက်စမ်း ဆိုတာမျိုးခိုင်းဖို့။ “ဒေါ်မြ၊ ဒီပန်းကန်ဘယ်လောက်လဲ၊ တစ်ဒါဇင်ယူရင် ဘယ်ဈေးလဲ၊ အလုံး ၅၀-၁၀ဝ တစ်ဆင်တည်း ရမလား” လို့မေးတဲ့လူ၊ “ဒေါ်မြ လက်ဖက်ရည်ခရားက ဒါပဲလား၊ ေြွကရေထူခရား မရှိတော့ဘူးလား၊ ကျွန်မတို့ အရပ်ဘုံသုံးအတွက် များများဝယ်ချင်လို့” ဆိုတဲ့ ဈေးဝယ်၊ “ဒကာမကြီး၊ အလှူအကူပြန် လက်ဖက်ရည်ကြမ်းပန်းကန် ဘယ်နှမျိုးရှိလဲ၊ ပြစမ်းဗျာ၊ အလုံး ၁၀ဝ ဘယ်ဈေးလဲ၊ ၅၀ဝ၀ လောက်ဝယ်ရမှာ” လို့ပြောတဲ့ ဘုန်းတော်ကြီးနဲ့ သူ့ဒကာ၊ “အမေမြ မင်္ဂလာဆောင်လက်ဖွဲ့ချင်လို့ ဒင်နာဆက်ဘယ်နှစ်မျိုးရှိသလဲ ပြစမ်းပါ” ဆိုတာကတစ်မျိုး၊ “ထမင်းစား ပန်းကန်ကလေး သုံးချပ်လောက်လိုချင်တာပါ” ဆိုသူကတစ်ဖုံ၊ ဈေးဝယ်တွေ အားလုံးကို ဒေါ်မြက ပါးစပ်ဆိုင်းတီးသလိုတီးပြီး အားလုံးပြေပြေလည်လည် ဆက်ဆံပြောဆို ရောင်းချနေပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြ၊ အမေမြနဲ့ ဈေးဝယ်ခေါ်တဲ့အသံတွေဟာ တစ်ခါတလေ တစ်ပြိုင်တည်းထပ်နေတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြရဲ့ဆက်ဆံရေးက သိပ်ကောင်းတော့ ပန်းကန်ဝယ်ချင်ရင် ဒေါ်မြဆီ အရင်လာတာပဲ။ သူများဆိုင်သွားခဲတယ်။ သူကမရှိဘူး၊ သူနဲ့အဆင်မပြေဘူးဆိုမှ တခြားဆိုင်ကို ဒီဈေးဝယ်ကသွားတာပါ။ ဒေါ်မြဆိုင်မှာ ဝယ်သူဟာ စဲတယ်မရှိပါဘူး။

တစ်ပြိုင်တည်း တစ်ချိန်တည်းမှာ ဆယ့်လေးငါးဦးတော့ရှိနေတာပဲ။ ဈေးချိုကြီးထဲမှာ ပန်းကန်ရောင်းတဲ့ ဆိုင်တွေ အများကြီးရှိတယ်။ ဒါပေမယ့် ဈေးဝယ်က ဒီဆိုင်ကိုလာမယ်၊ ဒီဆိုင်မှာ ဒေါ်မြကိုသာမေးမယ်၊ ဒေါ်မြနဲ့ပဲ အားလုံးအရောင်းအဝယ်ကိစ္စပြတ်မယ်။ ဆိုင်ရှင်ဆိုတဲ့ ကုလားကြီး သူ့ဖာသာ ကုလားထိုင်နဲ့ထိုင်နေတာကို ရှိတယ်လို့ကို အသိအမှတ်မြုပဘူး။ ဒေါ်မြမရှိလို့ ဒီကုလားကြီးကဝင်ပြီး ဈေးပြောရင်တောင်မှ ဈေးဝယ်က ဒေါ်မြတွေ့အောင်စောင့်မှာ။ သူ့စကားမယုံဘူး။ သူနဲ့တော့ အရောင်းအဝယ်မပြီးပြတ်ချင်ဘူး။ ဒေါ်မြက နှုတ်စလျှာစကလဲ သိပ်ကောင်းတဲ့ အမျိုးသမီးကြီးကိုး။ ဆက်ဆံရေးကလဲ တကယ် တတ်ကျွမ်းသူပါ။ အားလုံးကျေနပ်အောင် ပြောဆိုတတ်တယ်လေ၊ မှတ်မိသေးတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြ လုပ်ပုံကလေး တစ်ခု၊ ကျွန်မတို့အဘိုးနဲ့အဘွားက သူ့ဆိုင်သွားပြီး ပန်းကန်ဝယ်ကြတယ်။ ကျွန်မက လိုက်သွားတယ်။အဘိုးဦးစိုးဂေါင်က ပိတ်ကုလားနံဖြူနဲ့ ရင်ဖုံးပင်ဖြူတိုက်ပုံနဲ့ ခေါင်းမှာ ပိုးပဝါ အဖြူကလေး ပေါင်းလို့။ကျွန်မတို့အဘွား ဒေါ်ရှမ်းမက ပြန့်ထမီအစိမ်းနဲ့မရမ်းကန့်လန့်စင်းနဲ့ ရင်ဖုံးအင်္ကျီ အဖြူကလေးနဲ့ ခေါင်းပေါ်မှာ သျှောင်တမာသီး ကလေးနဲ့၊ အသက်တွေကတော့ ၇၀ကျော်၊ ၈၀ နီးပါးတွေပေါ့။

အသားရေတွေက ဖြူဖြူစင်စင် သန့်သန့်ရှင်းရှင်း။ ပန်းကန်ဝယ်နေရင်း ဒေါ်မြက “ဒီအသက်အရွယ်အထိ ဒီလိုစုံစုံညီညီရှိတာ စိတ်ချမ်းသာစရာကောင်းလိုက်တာ” ဆိုပြီး အဘိုးနဲ့အဘွားကို သူကထိုင်ပြီး ကန်တော့ပါတယ်။ ဒါဟာ ပိုတာ၊ လောကွတ်လုပ်တာမဟုတ်ဘူး၊ တကယ်ကြည်ညိုလို့ ကန်တော့တဲ့ပုံ။

တကယ်ကတော့ ဒေါ်မြဟာ အစ္စလာမ်ဘာသာဝင်ပါ။ မန္တလေးက မြန်မာမွတ်စလင်ကို ဇေဒဘာရီလို့လဲ ခေါ်တဲ့လူကခေါ်တယ်။ ပသီလို့လဲ ခေါ်တဲ့လူကခေါ်တယ်။ နို့ပေမယ့် ဘာပဲခေါ်ခေါ် ဘာသာရေး ယုံကြည်မှုချင်းမတူတာကလွဲရင် သူတို့လဲ ဗမာတွေဆိုတာကို မန္တလေး မြန်မာ မွတ်စလင်တွေက သေသေချာချာပြပါတယ်။ ဗမာတွေကလည်း ဒီလိုသဘောထားတာပါပဲ။ ပြီးတော့ မန္တလေးက မြန်မာမွတ်စလင်တွေက တခြားအရပ်က မြန်မာမွတ်စလင်တွေနဲ့ ကွာခြားမှုရှိသေးတယ်။ သူတို့က မြန်မာမင်း လက်ထက်ကတည်းက မင်းချီးမြှောက်ခံမွတ်စလင်တွေဖြစ်လေတော့ မြန်မာမှုမှာ အလွန်ကျေညက်တယ်။ စကားအရာမှာ မန္တလေးသူ မန္တလေးသားထက် မညံ့တဲ့အပြင် သာလွန်သူတွေ အများကြီးရှိပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြက စကားတတ်တဲ့ ဗမာမွတ်စလင်အမျိုးသမီးကြီးတစ်ယောက်ပေါ့။ သူဈေးရောင်းကောင်းလွန်းတော့ ကုလားဗမာ အဓိကရုဏ်းကြီးဖြစ်တာတောင် သူက ကင်းလွတ်ခွင့်ရသတဲ့။ ၁၉၃၈ ခုနှစ်က မန္တလေးမှာလည်း ကုလားဗမာ အဓိကရုဏ်းဖြစ်တယ်။ ဖြစ်တော့ ရဟန်းပျိုတွေက ကုလားဆိုင်တွေမှာ မဝယ်ရဘူးလို့ ပညတ်ပေမယ့် ဒေါ်မြရောင်းတဲ့ဆိုင်ကို ချွင်းချက်နဲ့ဝယ်လို့ရသတဲ့။

ဒေါ်မြက အဲဒီလောက်ရေပန်းစားသူပါ။ သူ့ကို ဈေးဝယ်အားလုံးက အရောင်းဈေးသည်တစ်ယောက်သာပဲလို့ မထင်မှတ်ပါဘူး။ သူပဲဆိုင်ရှင်လို့ ထင်တာပါ။ ဖွာဇူလာနန်ဂျီမှာ ဘကြူးဘိုင်ခေါ်တဲ့ သားတစ်ယောက်ရှိပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြဈေးရောင်းနေရာကို တစ်ခါတစ်ရံ ဈေးနည်းနေတယ်ထင်လို့ ဘကြူးဘိုင်က “အမေမြ ဈေးတွေဘာလို့ သိပ်လျှော့ရောင်းနေတာလဲ” ဝင်ပြောရင် ဒေါ်မြက သူ့လာဘ်နဲ့သူ၊ သူလျှော့ပေးသင့်တယ်ထင်လို့ လျှော့တာ၊ နောင်အလားအလာ လာဘ်တစ်ခုခုကို မျှော်ကိုးပြီးလျှော့ပေးတာမျိုး ဖြစ်ချင်ဖြစ်မယ့်ဟာကိုး။ လူငယ်က ဘာမှမသိဘဲဝင်ပြောရင် ဒေါ်မြက “ရှာမရှည်နဲ့။ မင်းတို့ဗမာပြည်လာတုန်းက လံကွတ်တီနဲ့လာတာ၊ မင်းတို့ကို ဗမာတွေက ဘယ်လောက်အားပေးသလဲ၊ ငါလျှော့သင့်တယ်ထင်လို့လျှော့ပေးတာ” လို့ငေါက်ငန်းနိုင်ပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြ ငေါက်တာကို ဆိုင်ရှင်အဖေကြီးက လက်ခံရတယ်လေ။ လက်မခံလို့မဖြစ်ဘူး။ သူ့ဆိုင်အဖို့ ဒေါ်မြဟာ မရှိမဖြစ်တဲ့ဆိုင်ထိုင်မဟုတ်လား။ တောကလာတဲ့ဖောက်သည် အလှူဈေးဝယ်တစ်ဦး၊ ဒီအလှူဝယ်က ဒေါ်မြလက်ကို သူလိုချင်တဲ့ပန်းကန်ခွက်ယောက်ပစ္စည်းစာရင်းကို ထိုးအပ်ပစ်ခဲ့တယ်။ သူ တစ်ခြားပစ္စည်းတွေလိုက်ဝယ်ချေအုံးမယ်၊ တောင်းထ ဲရွေးချယ်ထည့်ထားနှင့်၊ အကွဲအအက် မပါစေနဲ့၊ ဈေးအနဲဆုံးနဲ့ အမျိုးအမှား၊အဖိုးမများအောင်သာ ဂရုစိုက်ပါလို့ ပြောသွားတယ်။ ဒီလူက အလှူအတွက် ပစ္စည်းအမျိုးစုံ ဝယ်ခြမ်းပြီးတော့ဒေါ်မြဆိုင်ကို အပြန်မှာမှ လှည့်ဝင်လာတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြက “အေး၊ မင်းစာရင်းမှာပါတဲ့အတိုင်း ငါထည့်ထားပြီ။ ဟော့ဒီမှာ မင်းဝယ်တဲ့ပစ္စည်းစာရင်း၊ မင်းတောင်းထဲမှာ ဒီစာရင်းပါပန်းကန်တွေ အပြည့်အစုံအပြင် မင်းတို့အလှူကို ငါကူလိုက်တာလဲပါတယ်” တဲ့။ ဒီလိုအလုပ်မျိုးကို ဆိုင်ရှင်ကုလားကြီးနဲ့ဆိုရင် ဘယ်မှာ ဖြစ်လိမ့်မလဲ။ ဒေါ်မြမို့ပေါ့။

ဈေးဝယ်က အဲ့ဒီလိုယုံမှတ်အောင် တည်ဆောက်ထားတဲ့ သမာဓိလည်း သူ့မှာ ရှိပြီးသား။ ဒါဟာ ရောင်းအဝယ်မှာ အရေးကြီးဆုံး အရည်အသွေးပါ။ အရောင်းအဝယ်ကြီးတွေ ပြည်သူပိုင် သိမ်းတော့ ဒေါ်မြက သူ့အိမ်မှာ သူပြန်ပြီးတော့ ထိုင်နေပါတယ်။ အဲဒီတော့ ဆိုင်ရှင်က ဒေါ်မြ မလုပ်နိုင်ရင် နေပါ။ ဆိုင်မှာမျက်နှာပြရုံတော့ လာပါဦးလို့ လာခေါ်ပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြဟာ အသက် ၁၈ နှစ်သမီးကစပြီး အသက် ၉၀ အရွယ်အထိ ဈေးချိုထဲမှာနေသွားပါတယ်။

အသက် ၉၀ မှာ တိုက်ဝယ်ချင်သူတစ်ယောက်ကို ရောင်းမယ့်တိုက်လိုက်ပြတော့ အုတ်ခဲကျိုးနင်းမိလို့ ခြေခွင်လဲတယ်။ အဲ့ဒီတော့ သူအိပ်ရာက မထနိုင်တော့ဘူး။ အိပ်ရာထဲမှာ ၂ နှစ်နေသွားပြီး အသက် ၉၂ နှစ်မှာသေဆုံးသွားပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြဆုံးရှာတာ ၂၂.၈.၇၂ ခုနှစ်က ဆုံးတာတဲ့။ ဒေါ်မြရဲ့မြေး ခင်မမက မန္တလေးတက္ကသိုလ် ပါဠိနဲ့ အရှေ့တိုင်းပညာဌာနမှူး ဦးကိုကိုရဲ့ဇနီးကိုး။ ဦးကိုကိုရဲ့သားအကြီးဆုံး ဦးစိုးမြင့်ကတော့ ပညာရေးဘက်မှာလည်း ဆရာလုပ်တယ်။ ရွှေရုပ်လွှာသနပ်ခါးလဲ ထုတ်လုပ်ပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြဘဝက လင်ကံမကောင်းရှာဘူး၊ ယူတဲ့လင်က ပထမအိမ်ထောင်ဟာ ၄ လဘဲပေါင်းရပြီး မုဆိုးမဖြစ်ရတယ်။ ဒုတိယအိမ်ထောင်ထူတော့ အဲ့ဒီအိမ်ထောင်က အလွန်ဆိုးတဲ့လူ၊ ဒေါ်မြကိုရိုက်တယ်၊နှက်တယ်၊ မီးတွင်းထဲတောင်ရိုက်လို့ မပေါင်းနိုင်တော့ သားကလေးရင်ခွင်ပိုက်ပြီး ယောကျာ်းဆီက ဆင်းပြေးလာတယ်။ ဒီသားလေး သက်ဆိုးမရှည်ဘူး သေသွားတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြက အဲ့ဒီတော့ သူ့တူမကမွေးတဲ့ မြေးခင်မမကို ရင်ဝယ်ပိုက်ပြီး တသက်လုံး နောက်အိုးနောက်အိမ်မထူထောင်တော့ဘဲ နေပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြ အိမ်ထောင်ရေးနဲ့ပတ်သတ်ပြီး ပြောတဲ့စကားက “လင်များဆိုရင် စိတ်နာလွန်းလို့ အိမ်မှာ လင်ပန်းတောင် မထားချင်ဘူး” တဲ့။ ဒေါ်မြကိုင်စွဲတဲ့လူ့ဘဝဆောင်ပုဒ်က “လောကမှာ ပျော်ပျော်နေတာ အမြတ်ဆုံး၊ လူတိုင်းကို ချစ်ပါ။ လူမျိုးတွေဘာသာတွေ ထည့်မစဉ်းစားနဲ့” တဲ့။ ပြီးတော့ ဒေါ်မြက လူဆိုတာ မသေမချင်း အညွန့်မတုံးတဲ့လေ။ ဒေါ်မြက စစ်ကြီးဖြစ်တော့ မန္တလေးက မွတ်ဆလင်များခိုကိုးတဲ့ ဘုံးအိုးရွာကိုပြေးတယ်။ စစ်ပြေးဘဝမှာ စိန်ရွှေပွဲစား လုပ်စားခဲ့တယ်။

အသက် ၉၀ အရွယ်မှာ အိပ်ရာထဲလဲနေတော့ သူ့ကိုလူမမာမေးလာကြသူတွေက အများသား။ အဲ့ဒီထဲကတချို့က “အမေမြရယ်၊ အမေမြနေမကောင်းနေလို့၊ ကျွန်တော် ကျွန်မတို့က တိုက်ကလေးတစ်လုံးလောက် ဝယ်ချင်လို့၊ စိန်နားကပ်လေး ၇ ရတီလောက်လိုချင်လို့” ဆိုတာမျိုးပြောလာရင် အမေမြက“ရပါတယ် နေအုံး ဘယ်သူနဲ့ဆုံပေးမယ်။ ဘယ်သူရေသွားဟဲ့ ဘယ်သူ ခေါ်ချေစမ်း” ဆိုပြီး အိပ်ရာထဲကနေပြီး ပွဲစားလုပ်ပေးသေးတယ်။ သူနဲ့အတူနေပြီး မြေးမရဲ့သား ရွှေရုပ်လွှာဦးစိုးမြင့်က ကျွန်မကိုပြောပြတာ အမေမြ အိပ်ရာထဲပက်လက်ဘဝမှာ ပွဲခငွေသုံးသောင်း လောက်ရအောင် ရှာပေးသွားပါသေးသတဲ့။ ဒေါ်မြကစနေသမီးတဲ့။ ဒါပေမယ့် ဒေါသမကြီးတဲ့အပြင် သူတစ်ပါးအပေါ် သိပ်သည်းခံပါတယ်။ ဒေါ်မြကို ဈေးသည်ကောင်းကြီး တစ်ယောက်အဖြစ်နဲ့ မန္တလေး မြို့သူမြို့သားတွေက သူ့ကိုမှတ်မိ သတိရ နေကြတာပဲ။