After the brutal crackdown on university students on 7 July 1962, General Ne Win’s regime understood that brute force alone would not be enough to control Myanmar’s future. What the military feared most were thinking, organized, and morally courageous youth. So, they turned to a more insidious weapon: indoctrination disguised as opportunity.

Outstanding Student (Lu-Ye Chun လူရည်ချွန်) Project

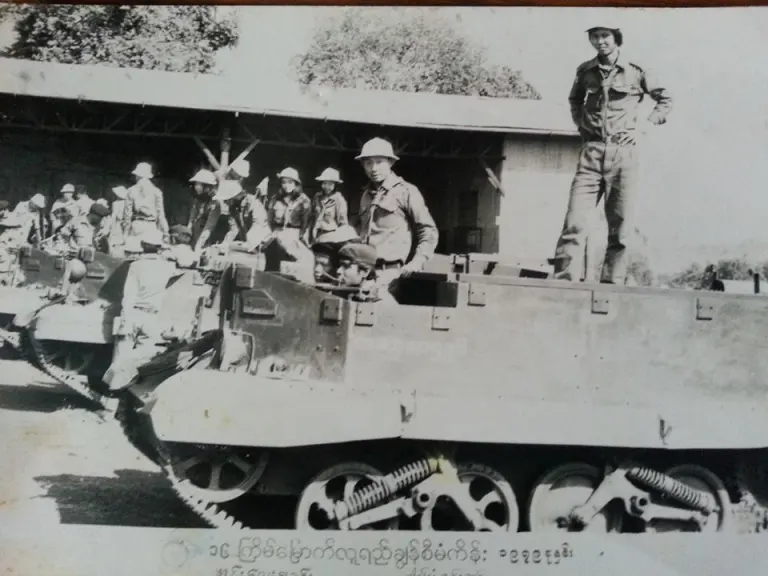

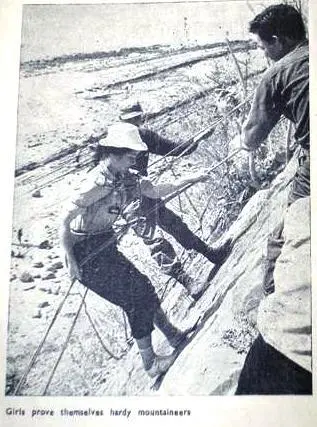

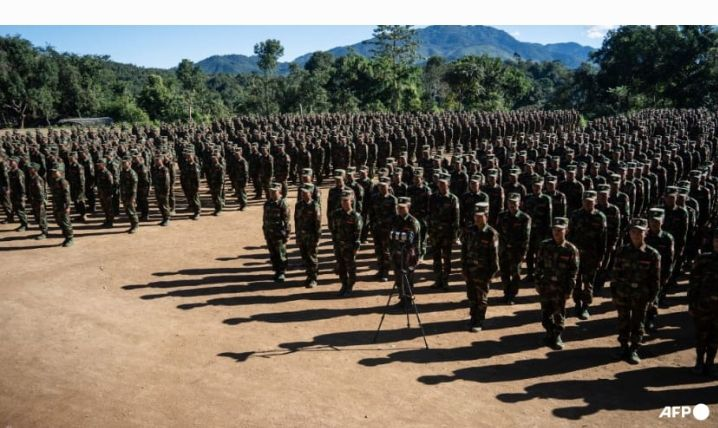

Thus was born the Lu Ye Chun (Outstanding Student) project—a nation-wide selection process rewarding high-performing students in academic subjects like general knowledge, mathematics, and Burmese, as well as physical fitness and discipline. Competitions were held at inter-class, township, and district levels, with final selections made by the Ministry of Education. On the surface, it was a meritocratic celebration of young talent. In reality, it was a calculated attempt to mold the next generation of state-loyal, apolitical, and obedient citizens.

But as history often teaches us: indoctrination does not always succeed. The Lu Ye Chun project may have planted seeds of loyalty—but in many cases, it also fertilized seeds of resistance.

Bright Minds, Diverging Paths

Indeed, the program produced an impressive roster of future generals, ministers, deputy ministers, rectors, professors, and other establishment figures. For a while, it served the junta well.

But alongside them were others—alumni who would later become outspoken critics of authoritarianism, defenders of democracy, and advocates for interfaith harmony and justice. Among the Lu Ye Chun ranks were individuals like the late Dr. Zaw Myint Maung, a respected physician who became Chief Minister under the NLD; U Thein Than Oo, a courageous lawyer who defended political prisoners, Dr Tin Myo Win former political prisoner and long-time personal physician of Burmese politician Aung San Suu Kyi; and numerous silent rebels whose names may not be public, but whose actions challenged military dogma.

Dr Zaw Myint Maung Wikipedia

Chief Surgeon of Muslim Free Hospital, Yangon, Wikipedia photo

Lawyer U Thein Than Oo Irrawaddy Photo

Many of these critical thinkers were, ironically, the very students who had been uplifted by a system designed to silence independent thought. They had excelled not just because of the regime, but often in spite of it.

A Brief Moment of Inclusiveness

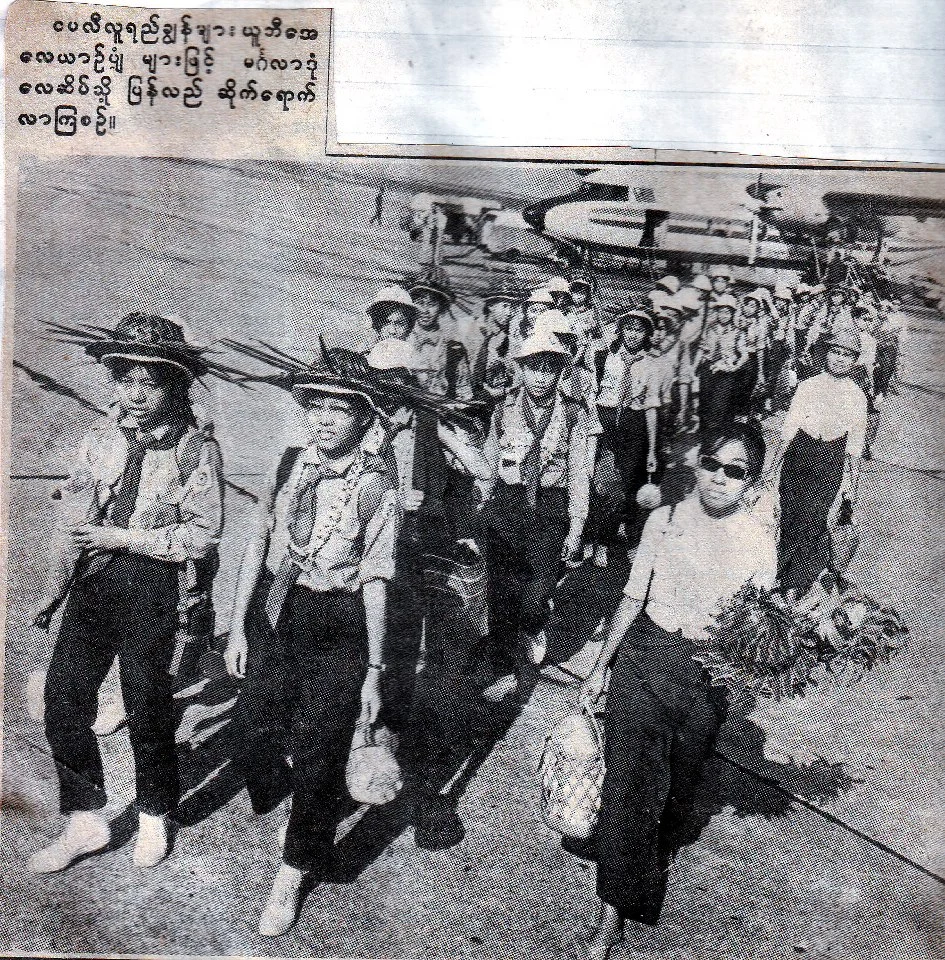

In its early years, the Lu Ye Chun program included students of all backgrounds, including Muslims and ethnic minorities. The selection was based on talent, not race or religion. This created a moment of hope—an illusion that the military might build a truly inclusive meritocracy.

Muslim Luyechuns or Outstanding Students

But that illusion crumbled in the decades that followed. As racism and Bamar Buddhist nationalism were increasingly woven into the fabric of the junta’s ideology, many former Lu Ye Chuns turned on their peers who advocated for marginalized communities, especially the Rohingya. Some were ostracized, expelled from alumni networks, and smeared simply for defending truth and justice.

What began as a competition of minds devolved into a bitter split between conformity and conscience.

A Legacy That Defied Its Creators

The irony is stark: a program designed to shape loyal patriots instead produced some of the country’s most principled dissenters. The military’s attempt to erase critical thinking ended up nurturing it. In that sense, the Lu Ye Chun project stands today as both a cautionary tale and a paradoxical success.

It shows that even under authoritarian rule, truth can survive—quietly at first, then courageously.

It reminds us that merit cannot be monopolized, and intelligence cannot be caged forever. And most importantly, it reveals that even in systems built to suppress, a few will always choose to think, to question, and to rise—not as tools of power, but as servants of truth.

Final Reflection

The nostalgia of Lu Ye Chun is bittersweet. Yes, it gave many of us unforgettable memories, forged lifelong friendships, and honed our abilities. But behind that glitter was a political agenda—to depoliticize and pacify the youth after one of Myanmar’s darkest moments.

The fact that so many alumni still live with moral clarity and courage is a testament not to the junta, but to the human spirit. In the end, Ne Win’s regime may have selected us—but we chose who we became.

And that choice makes all the difference.