End Torture, Arbitrary Arrest and Detention of Refugees

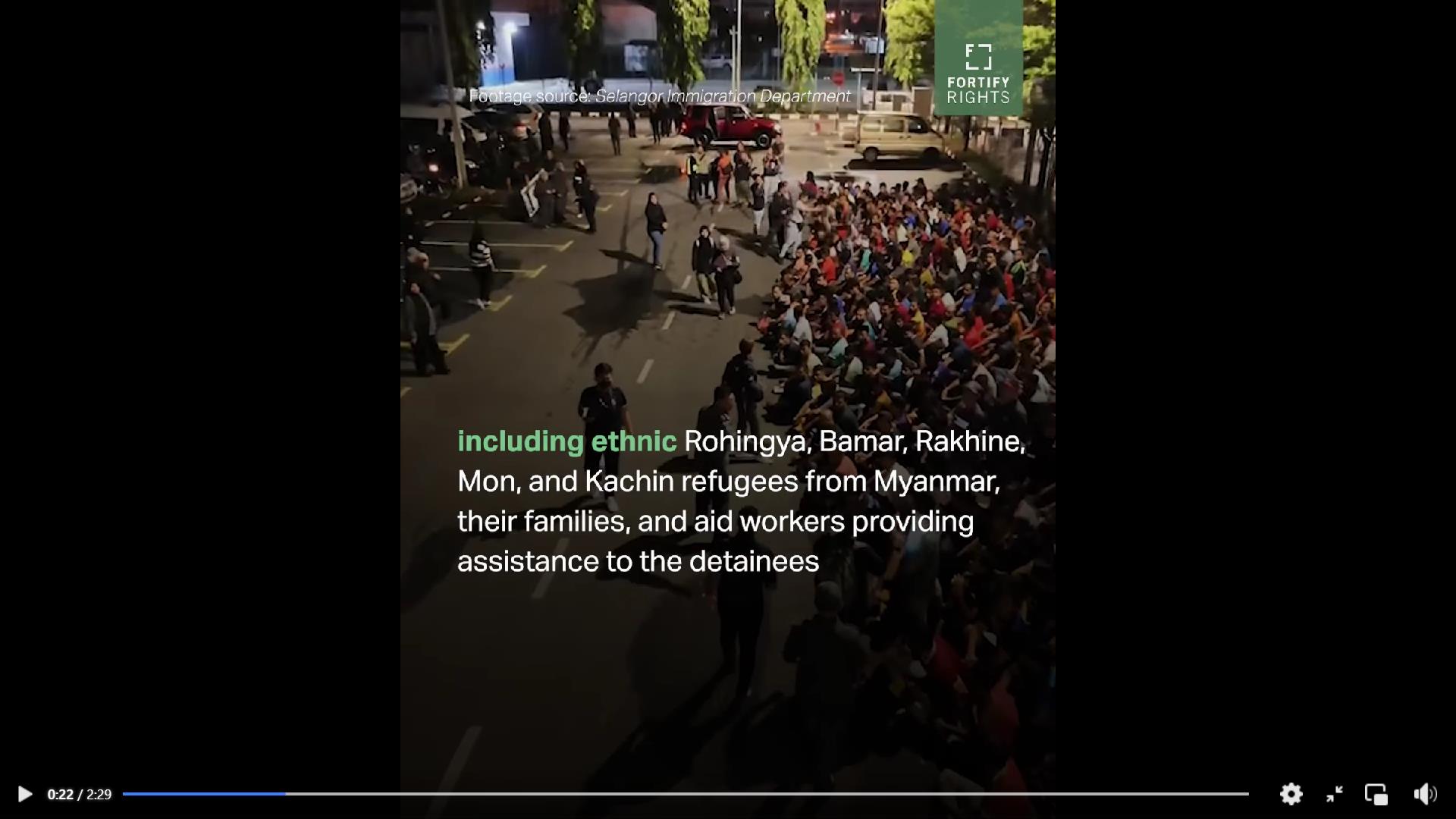

Detained refugees caught in government “repatriation” drive subjected to beatings, stress positions

(KUALA LUMPUR, June 18, 2025)—Malaysian authorities must end the use of torture in their Immigration Detention Centers (IDCs) and stop their arbitrary arrest raids against migrants, Fortify Rights said today. Several refugees, arbitrarily arrested and detained as part of a new campaign of immigration raids, told Fortify Rights that they were beaten, forced to maintain stress positions or stripped naked for prolonged periods, humiliated, and denied basic necessities while in detention.

“The use of violence and humiliation against refugees is unlawful and inhumane,” said Yap Lay Sheng, Human Rights Specialist at Fortify Rights. “Individuals seeking safety and protection from persecution are being met with mass arrest raids, discrimination, and abuse at the hands of Malaysian officials. The government must end its approach of indiscriminate raids to solving the problems of irregular migration.”

While ostensibly targeting undocumented migrants, the recent raids have resulted in the arbitrary arrest and detention of refugees, registered with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Malaysia.

Fortify Rights interviewed 17 victims and eyewitnesses of the recent immigration raids in Kuala Lumpur, Klang, and Muar, including former immigration detainees, their family members, humanitarians, and social workers. The interviewees include ethnic Rohingya, Rakhine, Bamar, Mon, and Kachin refugees from Myanmar. They described a dramatic surge in immigration raids in recent months that included arbitrary arrests and detention of refugees. Fortify Rights’ analysis of publicly available data shows that arrests for immigration-related offences have more than tripled in the past two years. Several refugees also told Fortify Rights how they were tortured while in the custody of Malaysian immigration authorities.

“Saiful,” a 58-year-old Rohingya refugee registered with UNHCR, who was detained in the Semenyih IDC in early 2025, told Fortify Rights that immigration officers tortured detainees as a form of punishment. “The officers told them [the detainees] to hold their ears and repeatedly sit down and stand up a hundred times,” Saiful said, “They [the detainees] were stripped naked of whatever they were wearing, even their underwear.”

Another Rohingya refugee, “Amar,” 25, described verbal abuses while being strip-searched in Semenyih IDC in February 2025:

They told us to take off our clothes. … We took off the clothes and I felt shame to see all my people [treated] like this. Then they told us to sit and they said that we are doing wrong things in their country. … They called us animals, called us dogs.

Rohingya refugee “Abdul,” 21, who was arrested and detained in the Semenyih IDC in early 2025, told Fortify Rights:

We were beaten in the IDC for talking. … Immigration officers came and beat us with black pipes on the soles of our feet. … They also beat us because the water they provided was too little … When we went to ask for more water, we were beaten.

“Hanif,” 30, a Rohingya refugee who was detained in the Bukit Jalil IDC in January 2025, also told Fortify Rights the torture he witnessed:

There were these three people who were interrogated. … I saw the officer smashing the phone on [one of the detainees’] forehead with the front screen. I saw that it was hurting him and he kept smashing until the phone screen broke. … I saw that he was in pain. He was crying.

In February 2024, “Razia,” 34, visited her husband at a police station where he had been detained on immigration-related charges, despite being a UNHCR-registered refugee. Razia told Fortify Rights that her husband showed signs of ill-treatment, “[M]y husband’s face was swollen. There was blood on his nose and his mouth. Before this [her visit], they had already beaten him.” During Razia’s visit with her husband, she witnessed police officers beat him:

For that one hour, … I could see my husband, but they didn’t give me permission to speak to him. When I tried to talk to him, … a policeman said, ‘We already told you, you cannot talk with your husband.’ At that time, one policeman came [to Razia’s husband] held his collar, then he punched his face. He punched his eye once. And they [police officers] pushed him around a lot of times.

Razia’s husband was then moved from the police station, but despite making direct requests to the police for information, Malaysian authorities have failed to tell Razia where her husband is. She has not seen or heard from him for more than a year. “I want to know where my husband is and I want to meet him again,” she told Fortify Rights. For more than a year, her husband’s whereabouts is unknown in what may amount to a case of a government-enforced disappearance.

On March 31, 2024, the Malaysian government launched a year-long “Migrant Repatriation Programme,” a program that offered irregular migrants an amnesty in exchange for agreeing to be repatriated to their home countries. Concurrently, immigration officials have vowed to “ramp up immigration operations nationwide … to create an ecosystem that is unconducive for illegal immigrants.” Some migrants hail from Myanmar, where they cannot safely return.

On May 17, 2025, Home Minister Saifuddin Nasution Ismail extended a further one-year extension to the programme. At the same time, the minister warned, “The immigration enforcement division has been instructed to redouble enforcement operations to detect and arrest any illegal migrant that still refuses to participate in the program.”

Data disclosed by the Ministry of Home Affairs shows that between January and May 13, 2025, immigration authorities have arrested 34,287 individuals, totalling an average of about 7,800 arrests per month for the first four months of this year. Fortify Rights’s calculations show a surge in the average number of immigration-related arrests from 2024, at approximately 3,900 per month and a more than threefold surge in arrests compared to the average monthly arrest of about 2,300 in 2023.

Refugees caught up in these raids reported that immigration officers ignored evidence of refugee status, including cards issued by UNHCR confirming the cardholder’s need for international protection, and in some cases discarding or destroying the official UN documents.

“Our refugee card is not valid, has no value, at that time,” Amar, a UNHCR-registered Rohingya refugee, told Fortify Rights. “When I showed them … They said, ‘This card is useless, no need to share U.N. cards. If you have passports, then show me.’” Another UNHCR-registered ethnic Rakhine refugee from Myanmar, “Tun,” 47, whose workplace in central Kuala Lumpur was raided in October 2024, told Fortify Rights that the authorities threatened him, “Your UNHCR card is not valid, I will tear it up and lock you up.”

Once in detention, former detainees and family members tell Fortify Rights that contact with the outside world, including family, legal representatives, and UNHCR, is extremely limited. Some detainees manage to call friends or family only after paying hefty bribes. Tun tells Fortify Rights, “I paid 300 ringgit [US$68] to speak for half an hour. We have to hide behind the door … to avoid the CCTV.” “Saira,” 29, described the ordeal of speaking to her Rohingya relative who was arrested in December 2024, “After she was arrested, she called me … For three minutes, we have to pay 150 ringgit [US$34]. … I deposited money into [the officer’s] personal account.”

Due to this difficulty, social workers and representatives of community-based organizations, who are often first responders to immigration raids, told Fortify Rights that without timely access to the detainee or their family members, it becomes difficult to notify UNHCR or initiate the verification for their refugee status.

Although Malaysia does not formally recognize UNHCR refugee status, in practice, authorities typically detain registered refugees for two weeks under a so-called “verification” process. “Kevin,” an aid worker who frequently responds to arrests in his community, told Fortify Rights that refugee detainees’ access to protection often hinges on whether someone outside is able to alert UNHCR.

We’ve seen a UNHCR cardholder detained past 14 days with no follow-through with UNHCR. … In another very similar case, … the family member informed UNHCR to follow through. So UNHCR was aware of the case and informed the depot where the person was held.

Since August 2019, the Malaysian government has barred UNHCR from entering IDCs, hindering effective oversight and protection of refugees and other vulnerable individuals.

The U.N. Convention Against Torture (UNCAT) defines torture as:

Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

While Malaysia is not a party to the UNCAT, customary international law dictates that the right to be free from torture is non-derogable, meaning that it cannot be contravened, suspended, or limited under any circumstance, and that the prohibition on torture is universal, regardless of whether countries have formally joined UNCAT.

Malaysia has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention, and authorities do not formally recognize UNHCR cards as conferring legal status to cardholders. Under Malaysia’s Immigration Act 1959/63, anyone who lacks a “valid entry permit” is considered “illegal” or “prohibited” immigrants. Under Section 35 of the Act, officers can arrest “without warrant” any person “reasonably believed” to be liable for removal.

Although Malaysia is also not a party to the 1951 U.N. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (the Refugee Convention) or its 1967 Protocol, the Convention provides authoritative guidance on refugee protection under international law.

Under the Convention, a refugee is defined as a person unable or unwilling to return to their country due to a well-founded fear of persecution. Article 31 of the Refugee Convention notes that refugees should not be penalized, including through arrest or detention, in relation to their irregular entry or stay in a country of asylum, recognizing the fact that individuals fleeing persecution cannot always obtain proper documentation or official authorizations.

Failure to ratify international conventions is not a valid excuse for Malaysia to violate the rights of refugees, said Fortify Rights.

“Malaysia must end these indiscriminate immigration raids, provide formal refugee status to people whose lives are in danger in their home countries, restore UNHCR’s full access to detention centers, and put in place clear safeguards so that no one fleeing persecution is tortured, arbitrarily arrested, detained or forcibly returned,” said Yap Lay Sheng. “Refugees and asylum seekers must not be caught up in the dragnet of Malaysia’s migration policies.”