A Satirical Re-reading of Pagan History

“Scandals, Plots, and the Convenient Path to the Throne: A Satirical Re-reading of Kyansittha”

In Burmese history, the road to the throne is rarely paved with flowers. More often, it is cleared by the sudden disappearance of fathers, brothers, rivals—and occasionally, loyal heroes. Against this background, King Kyansittha’s rise appears less like destiny and more like a remarkably well-managed sequence of “fortunate events.”

Kyansittha was born to Princess Pyinsa Kalayani of Wethali and Anawrahta, who at the time was still a senior prince under King Sokkate. His early life already carried the scent of scandal. While his mother was pregnant, she was banished from the court after Anawrahta was persuaded that she was not of true royal blood. The child grew up far from the palace, away from official recognition.

Later chronicles, perhaps sensing discomfort with this origin story, floated an alternative explanation: Kyansittha’s real father might not have been Anawrahta at all, but Yazataman, the Pagan official assigned to guard Pyinsa Kalayani on her journey. Thus, from birth, Kyansittha stood at the intersection of rumor, silence, and political convenience.

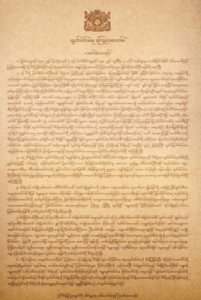

Stone inscriptions attempt to resolve this ambiguity with symbolism rather than clarity. Some describe Kyansittha as descended from a solar royal lineage on his father’s side, yet “born from within a bamboo stalk” on his mother’s—a poetic way of elevating humble origins into divine mystery. After all, if a king emerges from the people, the feudal system requires a prophecy to explain it. Myth repairs what genealogy cannot.

Anawrahta later bestowed upon him the name Kyansittha, usually translated as “the remaining soldier” or “the one who survives.” A flattering title—though historian George Coedès suggests it may simply be a corruption of a Pali term meaning “soldier-official.” Even survival, it seems, benefits from good branding.

During one of Kyansittha’s periods of exile or royal disfavor, he married Thanbula and fathered a son, Yazakumar. Or perhaps he did not—some accounts quietly cast doubt on the child’s paternity as well. Yazakumar, at least, behaved like a man who understood Pagan court politics very well. Rather than assert his lineage, he donated all his wealth—gold, land, servants, everything—to a pagoda dedicated to his father. In an age when relatives were often eliminated for far less, extreme generosity may have been the safest form of filial piety.

Romance also followed Kyansittha closely, particularly the famous episode involving Princess Manisanda of Pegu. While she was being sent as a diplomatic gift to King Anawrahta, Burmese chronicles delicately note that she and Kyansittha became “emotionally attached” along the way. History is polite like that.

Religious purity, too, proves less pure on closer inspection. During the construction of the new palace and major pagodas, rituals were conducted that had little to do with Theravada Buddhism: offerings to Vishnu, feeding of spirits, and naga worship all took place—while monks led by Shin Arahan dutifully recited protective verses. Pagan religiosity, it seems, was inclusive when politically useful.

Then there is the question of succession. Kyansittha may have arranged for his daughter Shwe Einsi to marry a Mon prince, Nagathaman, the grandson of King Manuha of Thaton. When a Mon-Burman grandson appeared, Kyansittha reportedly favored him as heir—even though he already had a biological son. Unity is a noble justification, but it is also a convenient one.

And what of Kyansittha’s fellow heroes? After the victory over Bago, where did the other three legendary comrades—Nga Htwe Yu, Nga Lone Let Phya, and Nyaung-U Phi—go? History falls strangely silent. Were they promoted? Retired? Or merely “removed from the narrative”?

Silence also surrounds the fate of other inconveniently popular figures, most notably Byatta, one of the two Arab brothers from Thaton. Byatta was no ordinary soldier. He was a foreign warrior of exceptional ability, beloved by the people and closely connected to the spirit-worship communities around Mount Popa. His relationship with the guardian spirit May Wunna produced two sons—the Shwepyingyi Brothers—perhaps among the earliest recorded Arab-Burmese lineages.

Byatta served Anawrahta loyally and played a decisive role in Pagan’s military victories. But in authoritarian systems, being indispensable can be dangerous. Some historians suggest that his execution was not a sudden royal impulse but the result of jealous ministers whispering into receptive ears. A hero with an independent base of support disrupts court equilibrium.

After Byatta’s death, the king took his sons under royal protection. Raised within the Kala Pyu Regiment, they proved fiercely loyal, even legendary—especially during the expedition to China for the Buddha’s Tooth Relic. One tale recounts how they infiltrated enemy territory without supplies, respected ritual hospitality, and chose restraint over assassination. Such men, one might think, would never betray the king who raised them.

Yet upon returning, fate—or perhaps paperwork—intervened. During construction of the Shwezigon Pagoda, every prince and soldier was ordered to contribute a brick. The Shwepyingyi Brothers failed to do so. Whether through distraction, belief, or design, two bricks were missing. The omission was interpreted as defiance. Punishment followed.

Some accounts quietly suggest that Kyansittha, uneasy about their popularity, played a role in framing the incident. Others say nothing at all. Again, silence does its work.

Finally, we arrive at the most sensitive episode: King Sawlu’s death. Was Kyansittha the loyal rescuer or the final beneficiary? Competing versions exist. One version claims Kyansittha acted decisively in enemy territory, knowing that a living Sawlu would complicate matters. Another portrays a struggle, a cry for help, and an irreversible act carried out in chaos.

Which account should we believe—Kyansittha’s or Sawlu’s?

History records one final removal. Yamankan, Kyansittha’s last serious rival, did not die in open battle or royal trial. In 1084, while retreating near Ywatha (close to present-day Myingyan), he was ambushed and killed by a hunter named Nga Sin. Chronicles note the event briefly. They are less curious about who gave the order.

Satire does not insist on an answer. It merely points out a pattern.

Exiled mothers. Disappearing rivals. Over-capable heroes eliminated. Loyal sons punished. Ambiguous rescues. And at the end of it all, a throne—cleared, stabilized, and sanctified by inscriptions.

I may be wrong. But there seem to have been too many scandals, plots, and schemes in Kyansittha’s life for all of them to be coincidence.

“And when modern generals choose Kyansittha as their idol, perhaps they recognize not the myths—but the method.”

Myanmar Junta Sithars and Their Idol Hero Kyansittha!

The junta is learning from History of Kyansittha’s Scandals, and the Convenient Path to Power” and does model itself on a Kyansittha-style myth:

- “Reluctant savior”

- “Order over chaos”

- “Stability justified by blood”