Dr Ko Ko Gyi @ Abdul Rahman Zafrudin

Most citizens—and even many officials inside Myanmar—do not realize that Lin Zin Kone, a small hillock near Amarapura, is one of the most historically layered sites in our country. It embodies the intertwined histories of Ayutthaya (Thailand), Lan Xang (Laos), Rakhine, Bengal, and Myanmar’s own Muslim literary tradition.

1. Who were the “Lin Zin” people?

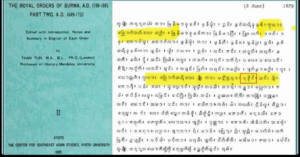

The term Lin Zin (လင်းဇင်း) frequently appears in Burmese chronicles and in The Royal Orders of Burma compiled by Dr. Than Tun. Contrary to common belief, Lin Zin does not refer to a tribe inside Burma, but to the Lan Xang Kingdom—the old Lao polity known as the “Land of a Million Elephants.”

Thus, the so-called “Lin Zin people” were Lao of the Tai/Shan–Tai family, closely related to today’s Lao and Thai.

Because Burmese chronicles often listed foreign polities among the “101 peoples,” Lan Xang appeared in those lists.

Lin Zin Kone likely received its name from settlements of these Lao/Tai captives during the wars of the 16th–18th centuries.

2. Burial of the Ayutthaya (Yodaya) King at Lin Zin Kone

After the fall of Ayutthaya, one captured Thai king was buried at this hillock.

To this day, Thai tourists quietly travel to Lin Zin Kone to pay respects to their lost monarch—something the Myanmar public rarely notices.

Instead of preserving or recognizing this important shared heritage, the Myanmar military recently, and foolishly, announced plans to demolish the hillock—claiming it was merely a burial site for a “Thai king and U Nu.”

Only strong public objections stopped the destruction.

A wiser government would have preserved and renovated the Thai royal tomb, developed a garden and historical signage, and promoted it as a symbol of centuries-old Myanmar–Thai cultural ties.

Look at India and Parkistan leaders visiting Myanmar paying respect at the last Mughal Emperor’s tomb in Yangon is a good example: Indian and Pakistani leaders both pay respect there, and funds have even been offered for its renovation.

Tourism, scholarship, and cultural diplomacy would all benefit from a similar approach in Myanmar.

3. Sayargyi U Nu: The Muslim Scholar at Lin Zin Kone

Few know that another distinguished figure rests at this same hillock: the renowned Myanmar Muslim writer Sayargyi U Nu, a classmate of King Bodawpaya at the Royal Monastery school.

Bodawpaya respected his scholarship so deeply that he personally asked U Nu to brief him on Islam.

U Nu responded by producing the earliest Burmese-language Islamic treatises, written in chapters similar to Buddhist scriptures:

- Islamic Book in Eleven Chapters

- Islamic Book in Three Chapters

- Saerajay Sharaei in 35 Chapters (reprinted in 1929)

- Guardian of the Burmese-Muslim Race (Upanishad-like scripture) – 1931

- Disciplinary Teachings in Seven Paragraph Poems

- Travel Diary of the Bengal Trip — considered the first travel diary in Burmese literature

His Bengal diary proved so valuable that Bodawpaya used the information to guide the 1784 annexation of the western Rakhine kingdom, which had remained semi-independent since the fall of Bagan.

U Nu’s insights also strengthened relations with Manipur, which Bodawpaya formally annexed in 1813.

Recognizing his brilliance, Bodawpaya appointed him:

- Royal Customs Officer

- Royal Purchasing Officer

- Mayor of Yammar Wati (Ramree Island) with the honorific Shwe Taung Thargathu — “Hero of the Ocean.”

His burial at Lin Zin Kone was not planned for political symbolism, but became an important coincidence tying Muslim, Thai, and Burmese histories together in a single place.

4. A Hillock That Deserves Preservation, Not Demolition

Lin Zin Kone is not just a mound of earth.

It is:

- The resting place of a Thai king,

- The tomb of a Myanmar Muslim literary giant,

- A historical settlement of Lan Xang (Lin Zin) Lao/Tai captives,

- A symbolic meeting point of Buddhist, Muslim, Thai, Lao, and Myanmar histories.

Destroying it would erase part of the shared past of the region.

Preserving it, renovating it, and presenting it properly could turn Lin Zin Kone into a meaningful site of historical reconciliation and international friendship.

In a time when Myanmar desperately needs bridges—not more divisions—protecting Lin Zin Kone would be a small but powerful step toward cultural wisdom.

Appendix

The shrine for the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, is located in Yangon (Rangoon), Myanmar, known as the Bahadur Shah Zafar Dargah, near the Shwedagon Pagoda. It’s a poignant, modest site where he was buried by the British after his exile, serving as a Sufi shrine and a significant spot for Indian history, marking the end of the Mughal Empire.

AI Overview

After the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, Burmese forces captured King Uthumphon (Tampon, likely a misremembering), his court, and many citizens, resettling them near Ava (Inwa) and later Amarapura (near modern Mandalay), where Uthumphon lived as a monk, leaving a significant Thai cultural footprint, including monasteries and historical records like the Yodaya Chronicle.

Key Details:

- The Event: The Burmese-Siamese War (1765-1767) culminated in the sack of Ayutthaya, the Siamese capital, by King Hsinbyushin’s forces.

- The Captives: Thousands of Ayutthayan nobles, royals (including King Uthumphon), and commoners were taken as prisoners to Burma (Myanmar).

- Resettlement in Burma:

- Initially, they were settled near Ava (Inwa).

- Later, as the Burmese capital shifted, they moved to Amarapura, near modern Mandalay, settling in villages like Yawahaeng (Rahaeng).

- King Uthumphon’s Fate: He lived for years as a revered monk in Burma, residing in monasteries like Yethaphan Kyaung and Paung Le Taik, eventually being entombed in a pagoda in Amarapura after his death in 1796.

- Cultural Legacy: This forced migration led to the creation of Thai-Burmese communities, documentation of Ayutthayan history in Burmese chronicles (Yodaya Chronicle), and Thai cultural elements found in the Mandalay region.

Addressing “Tampon”:

- “Tampon” likely refers to King Uthumphon (Maha Thammarachathirat III), the last king of Ayutthaya before its fall, whose name might have been corrupted over time.

The Yodaya ယိုးဒယား (Ayutthaya) Thai king’s tomb at the Linzin လင်းဇင်းကုန်း (Lang Xang) Laos hill

Credit to Nyi Win’s WP Blog.

The tomb of former Ayutthaya king Utumpon at Linzin hill, Taungtaman shore, Amarapura, near Mandalay, Myanmar

There have been news about the excavation of the Yodaya ယိုးဒယား (Ayutthaya) king’s tomb at the Linzin လင္းဇင္း (Lang Xang) hill at Mandalay (Taungtaman, Amarapura). It has been confirmed that it is the tomb of Ayutthaya king Utumpon. This led me to know more about the Linzin campaigns of the Konebaung era in 1763 and 1765 and also about the interesting life of king Utumpon.

First of all I wondered why the place is called Linzin (Lang Xang / Laos) hill and not Yodaya (Ayutthaya) hill.

While king Naungdawgyi was laying siege to the Toungoo, the vassal king loyal of Lan Na at Chiang Mai was overthrown.

After Toungoo was captured, Naungdawgyi then sent an 8000-strong army to Chiang Mai. The Burmese army captured Chiang Mai in early 1763

1763 – The Burmese invade Chiang Mai and the principality of Luang Prabang (now part of Laos) is captured.

It has also been mentioned that_

As a first step toward a war with the Siamese, Hsinbyushin decided to secure the northern and eastern flanks of Siam. In January 1765, a 20,000-strong Burmese army led by Ne Myo Thihapate based in Chiang Mai invaded the Laotian states. The Kingdom of Vientiane agreed to become Burmese vassal without a fight. Luang Prabang resisted but Thihapate’s forces easily captured the city in March 1765, giving the Burmese complete control of Siam’s entire northern border.

It must have been during these 2 wars with Lang Xang in 1763 and 1765 that captives from Lang Xang were taken back and settled near the Taungtaman lake, not far from Ava, and the place has been called Linzin hill since the time (Amarapura was not yet built at the time).

Burmese forces reached the outskirts of Ayutthaya on 20 January 1766. The Burmese then began what turned out to be a grueling 14-month siege. The Burmese forces finally breached the city’s defenses on 7 April 1767, and sacked the entire city. The Siamese royalty and artisans were carried back.

Hsinbyushin built a village near Mandalay for Uthumphon and his Siamese people—who then became the Yodia people. In accordance with Burmese chronicles, Uthumphon, as a monk, died in 1796 in the village. His is believed to be entombed in a chedi at the Linzin Hill graveyard on the edge of Taungthaman Lake in Mandalay Region‘s Amarapura Township.

Ex-king Utumpon (2 months rule 1758) was among those taken back to Ava and settled near present day Mandalay. However, the last Ayutthaya king Ekathat (1758–1767) was not among those captured and taken back.

During the 1767 siege of Ayutthaya_

King Ekathat and his family secretly fled from the capital. The nobles then agreed to surrender. On April 7, 1767, Ayutthaya fell.

Siamese chronicles said Ekkathat died upon having been in starvation for more than ten days while concealing himself at Ban Chik Wood (Thai: ป่าบ้านจิก), adjacent to Wat Sangkhawat (Thai: วัดสังฆาวาส). His dead body was discovered by the monk. It was buried at a mound named “Khok Phra Men” (Thai: โคกพระเมรุ), in front of a Siamese revered temple called “Phra Wihan Phra Mongkhonlabophit” (Thai: พระวิหารพระมงคลบพิตร).

King Utumpon was king of Ayutthaya for only 2 months after the death of his father king Borommakot.

One year before his death, Borommakot decided to skip Ekkathat and appointted Ekkathat’s younger brother, Uthumphon, as the Front Palace.

In 1758, Borommakot died. Uthumphon was then crowned, and Ekkathat entered in priesthood to signify his surrender. However, two months after that, Ekkathat returned and claimed for the throne.

1758, Aug – King Utumpon abdicates the throne and retires at Wat Pradu. He is succeeded by Prince Ekatat who assumes the title Boromaraja V

1760, Apr – King Alaungsaya lays siege on Ayutthaya. Siamese King Ekatat who senses that he is not up to the task of leading the defense of the city invites his younger brother, the former King Utumpon to rule temporarily in his behalf.

Only five days into the siege, however, the Burmese king suddenly fell ill and the Burmese withdrew.. (The Siamese sources say he was wounded by a cannon shell explosion while he was inspecting the cannon corps at the front.).

1762 – With the Burmese danger contained, Utumpon retires again and returns to his monastery, leaving the fate of Siam in the hands of his older brother, King Ekatat

The Burmese, however, came back in 1767 under the commission of Hsinbyushin and led by Neimyo Thihapate. Though he was strongly urged to take role in leading Siamese armies, Uthumphon chose to stay in the monk status. Ayutthaya finally fell. Uthumphon was captured by the Burmese forces and was brought to Burma along with a large number of Ayutthaya’s people.

Uthumphon was grounded near Ava, along with other Ayutthaya ex-nobles, where he was forced by the Burmese to give them knowledge about the history and court customs of Ayutthaya—preserved in the Ayutthayan affidavit. Hsinbyushin built a village near Mandalay for Uthumphon and his Siamese people—who then became the Yodia people. In accordance with Burmese chronicles, Uthumphon, as a monk, died in 1796 in the village. His is believed to be entombed in a chedi at the Linzin Hill graveyard on the edge of Taungthaman Lake in Mandalay Region‘s Amarapura Township.

Thai Cultural Village to Be Built in Burma

By YAN PAI / THE IRRAWADDY| Friday, May 3, 2013 |

http://www.irrawaddy.org/archives/33591

A Thai cultural village is set to be built near the Burmese city of Mandalay, reflecting the ancient Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya in a joint project Burma and neighboring Thailand.

Thailand’s Siam Society is reportedly seeking permission from local authorities in Mandalay to build the village at the edge of Taungthaman Lake in Amarapura Township, in a bid to preserve the culture of Thai people living in Mandalay in the 18th century.

The Siam Society, under the Thai royal patronage, was founded in 1904 in cooperation with Thai and foreign scholars to promote knowledge of Thailand and its surrounding region.

The push to build the cultural village follows the discovery last month that the former Siamese King Uthumphon—better known in Thai history as King Dok Madua, or “fig flower”—and other royal family members were buried at a prominent graveyard near the lake.

“A lot of Thai people arrived in Burma as prisoners of war and asylum seekers,” said Mickey Heart, a historian and deputy chief the excavation team that uncovered Uthumphon’s tomb.

He added that a large number of Thai people from Thailand’s Tak Province later migrated to Burma because of internal disputes in Ayutthaya Kingdom and were allowed to settle in Mandalay’s Yahai Quarter.

According to Burmese history records, King Hsinbyushin, the third king of Burma’s Konbaung Dynasty, invaded the ancient Thai capital of Ayutthaya in 1767 and brought as many subjects as he could, including Uthumphon, back to his own capital, Ava.

Residential areas and markets were named after Thai people settling around Mandalay and Ava at the time, and even today, the region boasts elements of Thai culture in certain religious practices, cuisines, and arts and crafts.

“A hybrid culture, the combination of Burmese and Thai, emerged following the death of those who were brought from Ayutthaya,” said Heart. “The smell of that culture can be felt around Mandalay these days.”

Meanwhile, since the excavation of the former Siamese king’s tomb, Thai media has recommended the burial place as a tourist attraction for Thai travelers.

Although Thai historians initially disagreed over whether to excavate the tomb, the project was initiated by the Siam Society following a report by The Irrawaddy in July last year that the burial place would be destroyed by local authorities in Mandalay to make way for a new urban development project.

King Utumpon

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uthumphon

| Uthumphon อุทุมพร | |

| King of Ayutthaya | |

| King of Siam | |

| Reign | 1758 |

| Predecessor | Borommakot |

| Successor | Ekkathat |

| House | Ban Phlu Luang Dynasty |

| Father | King Borommakot |

| Mother | Krom Luang Phiphit Montri |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | 1796 Mandalay, Konbaung Kingdom |

Somdet Phrachao U-thumphon (Thai: สมเด็จพระเจ้าอุทุมพร)[1] or Phra Bat Somdet Phra Chao Uthomphon Mahaphon Phinit (Thai: พระบาทสมเด็จพระอุทุมพรมหาพรพินิต) was the 32nd and penultimate monarch of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, ruling in 1758 for about two months. Facing various throne claimants, Uthumphon was finally forced to abdicate and enter monkhood. His preference of being a monk rather than keep the throne, earned him the epithet “Khun Luang Ha Wat”[1] (Thai: ขุนหลวงหาวัด), or “the king who prefers the temple”.

Prince Dok Duea or Prince Uthumphon—”Dok Duea” (ดอกเดื่อ) and “Uthmphon” (อุทุมพร) are under the same meaning, “fig”—was a son of Borommakot. In 1746, his elder brother, Prince Thammathibet who had been appointed as the Front Palace, was beaten to death for his affair with one of Borommakot’s concubines. Borommakot didn’t appoint the new Front Palace as Kromma Khun Anurak Montri or Ekkathat, the next in succession line, was proved to be incompetent. In 1757, Borommakot finally decided to skip Anurak Montri altogether and made Uthumphon the Front Palace—becoming Kromma Khun Phon Phinit.

In 1758, upon the passing of Borommakot, Uthumphon was crowned. However, he faced oppositions from his three half-brothers, namely, Kromma Muen Chit Sunthon, Kromma Muen Sunthon Thep, and Kromma Muen Sep Phakdi. Uthumphon then reconciled with his half-brothers and took the throne peacefully.

Ekkathat, who had become a monk, decided to made himself a king only two months after Uthumphon’s coronation. The three half-brothers resented and fought Ekkathat, and they were executed by Ekkathat. Uthumporn then gave up his throne to his brother and leave for the temple outside Ayutthaya so as to become a monk.

1758, Aug – King Utumpon abdicates the throne and retires at Wat Pradu. He is succeeded by Prince Ekatat who assumes the title Boromaraja V

In 1760, Alaungpaya of Burma led his armies invading Ayutthaya. Uthumphon was asked to leave monkhood to fight against the Burmese. However, Alongpaya died during the campaigns and the invasion suspended. Uthumphon, once again, returned to monkhood.

1760, Apr – King Alaungsaya lays siege on Ayutthaya. Siamese King Ekatat who senses that he is not up to the task of leading the defense of the city invites his younger brother, the former King Utumpon to rule temporarily in his behalf

1762 – With the Burmese danger contained, Utumpon retires again and returns to his monastery, leaving the fate of Siam in the hands of his older brother, King Ekatat

1766, Feb – The Burmese begin their siege of Ayutthaya. King Ekatat again offers his brother Utumpon to lead the defence of the city but this time Utumpon declines.

1767, Apr 7 – After 14 months of siege, Ayutthaya falls and King Ekatat flees.

Uthumphon was captured by the Burmese forces and was brought to Burma along with a large number of Ayutthaya’s people.

Uthumphon was grounded near Ava, along with other Ayutthaya ex-nobles, where he was forced by the Burmese to give them knowledge about the history and court customs of Ayutthaya—preserved in the Ayutthayan affidavit. Hsinbyushin built a village near Mandalay for Uthumphon and his Siamese people—who then became the Yodia people. In accordance with Burmese chronicles, Uthumphon, as a monk, died in 1796 in the village. His is believed to be entombed in a chedi at the Linzin Hill graveyard on the edge of Taungthaman Lake in Mandalay Region‘s Amarapura Township

MMSY News

Photo news and interview by Thuta Maung

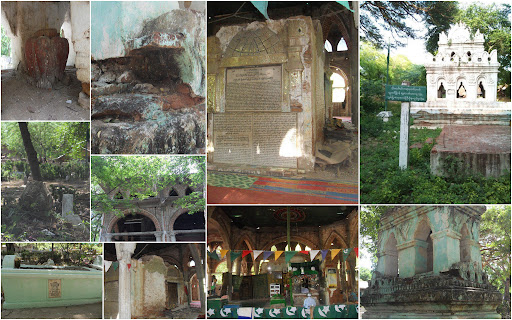

Lin-Zin-Kone Cemetery, the historic Myanmar-Muslim Cemetery dating back more than 200 years, situated in O-Daw Quarter, Amarapura, Mandalay, has been ordered to demolish before 1.7.2012, mentioned in the Mandalay Daily Newspaper on June the 1st to the 3rd. Regarding this, a visit to the cemetery was made, and the locals and persons in-charge there were interviewed.

Q: I want to ask some questions about the Lin-Zin-Kone Cemetery and the Durgah (The Shrine of the Muslim Saint (Wali) Abid Shah Husainni). Could you please explain a little about them?

A: We are in-charge for the Durgah, and the other young men take care of the cemetery.

Q: Rumors has it that the cemetery will be demolished soon. The newspaper said it would be terminated, but there has been hearsay about its extirpation. Have you had any updated news regarding that?

A: As this is a very historic place, we have appealed to the President, also signed by five Official Islamic organizations. As a result, the plan to demolish it is stalled for the time being.

Q: Could you please tell us the history this cemetery?

A: This place became a Kabar Stan (the Muslim Cemetery) because people who admire the Muslim Saint (Wali) Abid Shah Husainni have been burying their relatives here. Indeed the actually-located Muslim cemetery is on the other side of the street, beyond the wall. There used to be some buildings there. But during the Military Regime, that area was transferred to the Christians, and the Zagawa (the name of a type of flower Michelia champaca) Garden here was regarded as Muslim Cemetery. Actually, not even the whole garden is for the Muslims, only up to the graveyards of (The founder and donor of Basic Education High School 1) U E-Ko Ko Gyi’s wife Daw Daw Yan. The other part is for the Buddhists.

Q: So, the area till the brick wall belongs to the Muslim cemetery, right?

A: Yes, while we were fencing compound, it was called a halt, so the fence isn’t complete yet, actually only little is left, but we can’t continue because of the deterrent.

Q: Then anyway, the Muslim cemetery is said to be till that wall. What about the other side of the wall? Does it belong to the Christians?

A: There is a lane on the other side, and then, there are cemeteries for the Christians, the Chinese, and others. Actually, the area for the Muslim Cemetery was given to the Christians, and the garden land has been regarded as Muslim Cemetery. We Muslims have also been burying here, so this area is no longer seen as Durgah but as cemetery. Such a change happened during the Military Regime, and we couldn’t say anything against this.

Q: So, did this place exist long before as the Zagawa Garden? How is it so named and how has it become existed?

A: Yes, this has been actually a garden since Bo Daw Phaya (King Badon), while The Saint Abid Shah was meditating here on this land with Zagawa Flowers and trees, the Ponna Wun (Officer in-charge of the Brahmins) bought the land and donated it to The Saint. He was so pleased with the garden and said “I want to be buried here under the Zagawa tree when I die”. So the Ponna Wun, who was one of his disciples, make this land Waqf (donated the place for a special purpose) for the Saint, and his body was buried there as his will. It is believed in Islam that the place around the Saints is overwhelmed with (God’s) Allah’s mercy all the time. As people want to have that privilege, this place gradually became a cemetery as well, not purposely.

Q: What is the size of this area, both the Durgah and the cemetery?

A: The land that belongs to the Durgah is over 3 acres, and that for cemetery is 3 acres, so more than 6 acres in total.

Q: This Lin-Zin-Kone Cemetery is regarded as the historic place, isn’t it?

A: Yes, the Saint Abid Shah Husainni was a famous person. The King Bo Daw Min Tayar Gyi (King Badon) himself appointed him as the Chief Leader (Kazi – the prime judge) for Myanmar Muslims. And then Sayargyi U Nu was also buried here. He was also a very famous person, who wrote books on Islam in Myanmar Language, including one book exclusively written for the King. He also successfully accomplished what the King assigned him, and as a result was appointed as the Mayor of Ramayadi Town (in Rakhine State).

Q: Are there any other famous people buried here?

A: The Saint Abid Shah Husainni, Sayargyi U Nu, and then U Pein, the person who orgainsed building U Pein Bridge, the Mayor Bhai Sab, the Warrior U Yan Aung, and the Ponna Wun, and the like.

Q: So, tomb next to the Saint Abid Shah belongs to Ponna Wun, right? Is there any other famous people?

A: The one with official records are those, and there is tomb of U E-Ko Ko Gyi.

Q: Could you please tell us who U E-Ko Ko Gyi is?

A: He was the founder of Amarapura Basic Education High School, the one who sacrificed a lot for the school.

Q: Which one is Amarapura Basic Education High School? Is it the school nearby? Was he the founder of that school?

A: Yes, Amarapura No (1) BEHS. It is written on the monument stone pillar of the School’s Golden Jubilee as well. Once, Sayargyi U Htun founded Islamia National School in Mandalay. And then, when E U Ko Ko Gyi founded that school, it was first named National School. Later on, it was changed into Amarapura Basic Education High School. Now its name has become No.(1) BEHS, as there is No. (2) BEHS in Myit Nge.

Q: All right, let’s get back to the previous question. So, a letter of appeal has been sent to the President, right?

A: Not directly to the President yet. Only the copy of the letters sent to the Prime Minister and the other offices and ministries have been sent to the President. A letter to the President has been prepared, where almost 3000 people has signed in, requesting the President not to demolish such a historic place. Only as the last stage, we will be sending this letter to the President.

Q: So, you mean the letter hasn’t reached the Present yet, but it has reached to the minister, is that the Minister of Religious Affairs?

A: Both to the Minister of Religious Affairs and the Prime Minister of Mandalay Division.

Q: What did they reply responding your letters? Was the plan just halted without any reply?

A: For the time being, nothing has been done, demolishing hasn’t started. We were just told not to do anything right now. The five official Islamic organizations have also requested not to clear off that land, mentioning this area shouldn’t be demolished in these situations, the historic values of this area, and it is not allowed in Islam to demolish the cemeteries.

Q: So the authorities said not to do anything, and not to worry, they wouldn’t start to demolish it. Did they reply that in an official letter or just a verbal promise?

A: It was mentioned just verbally.

Q: Who said that then, the Minister of Religious Affairs or the Prime Minister of Mandalay Division?

A: The Minister of Religious Affairs of Mandalay Division U Than Soe Myint said that, and the Prime Minister of Mandalay Division is U Ye Myint.

The Durgah Daw (Tomb) of the Saint Abid Shah Husainni, the king’s appointed Leader of Muslims of Myanmar during the King Along Phayar (King Badon)

During the Crisis in 1997, the tomb was set to fire, and the renovation thereafter was also forced to discontinue

Q: As far as I know, the Durgah was also destroyed during the conflict in 1997. After that the renovation started, and then, why has it stopped before it was completely renovated? Were you not allowed to?

A: Yes, the permission to renovate this has been halted. After 1997 conflict, it was allowed to renovate, and it has been partially done as you can see at present, later on, it was ceased before it was complete, while the previous commander of Mandalay division was in-charge. We tried to have a chance to meet him and request him to let it continue, but we couldn’t as he refused to. When we applied for the renovation, the military government then permitted that with an official letter, but when we were ordered to stop renovating, it was only the Verbal Order, no written document at all. Now in the present government’s regime, Mandalay City and Development council just said not to do anything, but nothing was officially ordered from the authorities.

Q: So, can we say there has been no official order for discontinuation of renovation?

A: Yes, no officially written order, only verbal orders. But things might have caused worse if we hadn’t stopped, so we had to. But we are trying our best for that. As there is hope for better democracy here, things will be better we hope.

Q: Now, as we cannot bury here anymore, how are you arranging for that?

A: People from Amarapura have to go through four townships up to Kyar Ni Kan Cemetery. Normally, it is not allowed to carry a corpse through the townships, but now we have to pass through four townships, sometimes when it coincides with the VIP’s special route, we have to go through even five townships.

Q: It means that the corpses are carried from Amarapura the Southernmost to Kyar Ni Kan the Northernmost of Mandalay.

A: Exactly. Even for the car rental fee, it costs about 45,000 kyats to 50,000 kyats per car.

Q: May I ask you one thing? There are several monasteries around this Amarapura Lin-Zin-Kone Cemetery. How is the relationship with the monks there?

A: Yes, there are monasteries all around here. Sayardaw U Janakka Thara Biwonsa, the fonder and head monk of Mahar Gandaryone Monastery, has been very close to Khalifah U Maung Maung Gyi, the Leader of KAFTG Gharana Family. And also, Sayardaw U Pyinnyar Zawta (Ko Pyinnyar_Amarapura) from Taung Lay Lone Monastery even mentioned about Durgah in his book. Monks from the monasteries around here have a very good understanding towards us. We are also getting along well with them. Sometimes, we even offer food to our close monks. People with all creeds in Amarapura have mutual respect and understanding towards each other.

Q: My last question: You said in Amarapura, people from different religions show mutual respect and understanding, but how come the Durgah was set fire to, during 1997 conflict? What do you say about that?

Well, we could say in confidence that it wasn’t done by the monks nearby. The elder high-ranked monks here have a complete control over the younger ones from their monasteries. So, they were not from nearby monasteries.

Q: Thank you very much for your time. Last month we came to know that this Lin-Zin-Kone Cemetery would be demolished. So we come here today, even if it would be cleared off (May Allah forbid that), there could be something recorded left as historic proof or evidence. And we assume that most of the young people do not know about this historic place, and we wanted to make them aware of these sentimental values.

A: We are also glad to tell you about this. Here is a book on the biography of the Saint Abid Shah Husainni. You can learn the details about the Durgah.

Sayar U Pyinnyar Zawta ( pseudonym : Ko Pyinnyar_Amarapura) mentioned about “The Durgah Daw” in his book named “The Historic Places around Taung Thaman” (Appendix) Pg. 75 & 76, 1st Edition, 1996, and that was translated by Late renowned History Professor Dr. Than Tun as below.

“THE DARAGA DAW”

Arbhisha Hussaini’s tomb is commonly called the Daraga Daw. (Durgah is Persian meaning a royal court; with an extended meaning in India it is used to mean a shrine of a Mohammedian saint for prayer.) It is located on the north of Mezabin (Madhuca longifolia) avenue, west of “Red Pagoda” (Shwe Mutthaw Thein Hpaya), east of the wards called O-daw (Royal Potters) and Hmite Su (People engaed in reclaiming gold dust from the refuses collected from pagoda precincts and goldsmith’s workshop) and in the Lin Zin Gon cemetery.

Arbhisha Hussaini was born 1776 and came at the age of nineteen to Amarapura in 1795. He died at the age of only thirty nine in 1815 after serving the king as the leader of the Islamic people for twenty years.

He had written thirty books on Mohaedanism. At a funeral of a female devotee or Moree he came to sit under a Zagawa (Michelia champaca) tree and as he was so pleased with that place in the garden he said:

“I wish I would be buried here”. Surely his wish was fulfilled and a Durgah was built in his memory at his tomb under the Zagawa tree that he had chosen.

The Ponna Wun (Officer – in – Charge of Brahmins) bought the gardenand gave it to him before he died.

Credit : “The Biography of Hazarat Sayyid Khwaja Hafiz Muhammed Sharif Abid Shah Husainni” published by The Durgah Daw Trustee Committee, Page 34, 34, 36.