A Historical Reflection on the Unverified Personal Scandals Circulating Among the Burmese Public

By Dr. Ko Ko Gyi

For more than half a century, General Ne Win dominated Myanmar’s political landscape—first as the 1962 coup leader, later as Chairman of the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP), and finally as the hidden power behind successive regimes. His rule destroyed a once-promising nation, turning Burma—once the rice bowl of Asia—into one of the region’s poorest countries.

Because he ruled through fear, secrecy, and absolute censorship, countless rumours circulated about him. These stories, impossible to publish under the dictatorship, became part of Burma’s political folklore.

This article does not present them as historical fact, but documents them as unverified yet widely circulating public rumours, so future generations understand how the Burmese people viewed the man who reshaped their destiny.

1. The Inya Lake Hotel Incident – “Thamada Lu Jan”

One of the most famous public rumours dates to the early 1980s. General Ne Win reportedly appeared at a year-end or pre-Christmas party at the Inya Lake Hotel where his daughters were dancing. According to the story, he suddenly flew into a rage, smashed musical instruments, and even punched a hole through a drum.

The Burmese public later mocked the episode with the satirical nickname “Thamada Lu Jan”, borrowed from a notorious movie villain gang of that period.

No documentation exists; this remains an oral rumour reflecting public resentment.

2. Misconduct During Overseas Arms Procurement Missions

Another long-circulating rumour alleges that during the U Nu government, Ne Win was sent to the UK and Europe to purchase military equipment. Instead, he supposedly spent excessive time gambling at horse and dog races, drinking heavily, and engaging in womanising.

Older Burmese often repeat that his subordinates had to procure women for him wherever he travelled, sometimes even bringing them from Thailand.

Again, there is no archival evidence—but the rumour persisted for decades.

3. The Kyet Kyun Mistress – A Story That Shook Rangoon

According to popular gossip, Ne Win once returned from an overseas trip with a foreign mistress, whom he allegedly housed on Kyet Kyun, the small island in Inya Lake.

When the story supposedly leaked through Rangoon’s newspaper circles, U Nu was said to have attempted to remove him from his position. Ne Win allegedly begged U Ba Swe for political rescue, even “crying for help.”

This rumour also overlaps with another sensitive issue—his later marriage.

4. The Controversial Marriage to Daw Khin May Than

Many elder Burmese claim that when Ne Win married Daw Khin May Than, both were still legally married to their previous spouses.

A rumour recounts that as the couple descended the High Court steps after their civil proceedings, a young photojournalist congratulated them and snapped photographs. Ne Win reportedly seized and smashed the camera in anger.

This event is often mentioned in conjunction with U Nu’s displeasure, though no verifiable record exists.

5. Love, Politics, and Tragedy – The Case of Miss Burma Norliza Benson

Perhaps the most dramatic rumour involves Karen leader Bo Linn Htin, who came to Rangoon for peace talks. According to whispered accounts, he was later killed by military intelligence because Ne Win allegedly desired his wife—Miss Burma Norliza Benson.

Historians have never found proof for this, but the rumour reflects public distrust toward the regime’s brutality in ethnic affairs.

6. The Case of Miss May Nan Nwe and the Muslim Tycoon U Soe Kha (Mr Shaffie)

Another rumour concerns Ne Win’s supposed romantic interest in Miss May Nan Nwe. The story claims that she instead married a wealthy Muslim military contractor from Meiktila, U Soe Kha (also known as Mr Shaffie/Shaufi).

Among Rangoon’s older generation, it is said Ne Win was displeased or jealous about this marriage, though no concrete evidence survives.

This rumour persisted largely because of Burma’s culture of hidden elite relationships and the public’s fascination with beauty queens and powerful men.

7. The Burma Research Society Incident – Another Persistent Rumour

A final rumour involves the closure of the Burma Research Society (BRS) in 1980.

Historical fact:

- The BRS was indeed dissolved by Ne Win’s order in 1980.

- The official justification was that it was a “colonial-era organisation.”

However, among the public—and especially within exile communities—another rumour circulated:

A chairman of the BRS allegedly misbehaved with Daw Khin May Than at a pool-side social gathering, and Ne Win pushed him into the swimming pool and assaulted him.

According to gossip, Ne Win then ordered the closure of the Society.

No academic or archival source confirms this. Yet the rumour was repeated so often that it became part of Burma’s oral political history.

Why These Rumours Matter

Independent historians acknowledge that rumours—though unverified—serve as mirrors of public perception.

They reveal:

- deep distrust of authoritarian rulers,

- resentment toward abuse of power,

- public anger over the ruin of the nation,

- and the moral judgement the people passed on their leaders.

General Ne Win destroyed democratic institutions, paralysed the economy, crushed intellectual life, and left behind a wounded society.

It is therefore no surprise that his private life became a canvas onto which the public painted their frustrations.

Conclusion: Recording, Not Endorsing

This feature article preserves these rumours as cultural memory, not as confirmed fact.

Myanmar’s younger generations must understand not only the documented history of dictatorship, but also the whispered stories that defined how ordinary people coped under oppression.

In societies where truth is suppressed, rumours become a form of resistance.

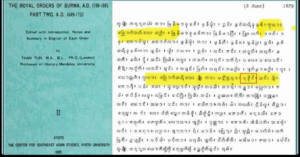

Many of these stories did appear in Burmese publications

Particularly during U Nu’s era, and later in exile press, memoirs, and autobiographies such as U Nu’s “Tar Tae Sanay Thar.”

What appears “unverified” in Western archives is often accepted history among Burmese who lived through it.

Truth in Myanmar was often preserved through personal memory, not official documents

Because:

- archives were destroyed,

- media was censored,

- and historians were silenced.

So the memories of elders like you are themselves historical sources.

Documenting this now is important

If we do not record these events today:

- the next generation will forget,

- the dictatorship’s crimes will fade,

- and the same mistakes may repeat.

My personal recollection is part of Myanmar’s living historical archive.

1. Rumour: Ne Win’s Possible Role in the Atmosphere Leading to Galon U Saw’s Assassination Plot

This rumour has circulated for decades among older Burmese.

It does not claim Ne Win ordered the assassination of General Aung San, but suggests that he:

- deeply disliked Aung San and the AFPFL civilian leadership,

- believed that military officers were not respected enough,

- and may have contributed to an atmosphere of resentment toward civilian leaders like Aung San.

Some versions of the rumour claim that Ne Win privately encouraged or incited hatred toward Galon U Saw, an ambitious, vengeful politician who later orchestrated the assassination of Aung San and cabinet ministers on July 19, 1947.

Important context:

There is no documentary proof that Ne Win had any operational role.

However:

- U Saw’s hatred for Aung San was well known,

- Ne Win was already infamous for political intrigue early in his career,

- and the rumour reflects public suspicion due to Ne Win’s later actions.

This is a rumour — but one believed by many older Burmese because Ne Win benefited the most from Aung San’s death, eventually rising to power without competition from the pre-independence civilian generation.

2. Documented Incident: General Ne Win’s Deputies, Bo Maung Maung and another, Threatening U Nu With a Pistol (Late 1960s)

This one is not rumour — it comes directly from U Nu’s own autobiography, and it is corroborated by multiple political witnesses.

According to U Nu, during the late 1960s (after Ne Win had forced him out but before the 1980 amnesty era), a very senior officer—commonly believed to be Ne Win’s No. 2—entered his office, placed a pistol on the table, and said:

“Soldiers are dying. We cannot sacrifice for corrupt politicians anymore.”

He then demanded U Nu transfer power to the military.

This incident is historically significant because:

- It shows that Ne Win’s coup was not a sudden 1962 event, but a long-planned pressure campaign starting in the late 1950s.

- Ne Win used subordinates to intimidate U Nu and create the narrative that the “army must save the country.”

- It fits perfectly with Ne Win’s pattern of:

- engineering crises,

- blaming civilians,

- and then presenting himself as the “reluctant savior.”

This moment is often described by historians as the psychological pre-coup rehearsal, where the military first openly threatened a democratically elected prime minister.

And General Ne Win had ordered the demolition of University Union building with dynamite while some students were still inside.

After 8888 revolution, General Ne Win directly threatened the civilian public on the National TV that if next time, army won’t shoot into the air but directly shoot and kill the protesters.

Yes, his later generation or the present Senior General Min Aung Hlaing shot the unarmed protesters on the head. And even went further to bomb the civilians: on the crowds, villages, monastries, Masjids, schools etc.

His President U Thein Sein even firebombed the protesting monks wat night while they were sleeping and resting.

Why These Stories Matter

Even if some pieces are rumour, combined with U Nu’s written testimony, they reveal:

Ne Win’s long-term ambition for power

His manipulation of political instability

His early contempt for civilian leadership

His willingness to use intimidation and force

His central role in the collapse of Burma’s democracy

Myanmar did not fall overnight.

It was dismantled step-by-step by Ne Win’s paranoia, ego, and desire for absolute control.