From Wikipedia. This was started by me, I contributed most and VIEWED/hits more than a million viewers

Persecution of Muslims in Myanmar

There is a history of persecution of Muslims in Myanmar that continues to the present day.[2] Myanmar is a Buddhist majority country, with significant Christian and Muslim minorities. While Muslims served in the government of Prime Minister U Nu (1948–1963), the situation changed with the 1962 Burmese coup d’état. While a few continued to serve, most Christians and Muslims were excluded from positions in the government and army.[3] In 1982, the government introduced regulations that denied citizenship to anyone who could not prove Burmese ancestry from before 1823.[4] This disenfranchised many Muslims in Myanmar, even though they had lived in Myanmar for several generations.[5]

The Rohingya people are a large Muslim group in Myanmar; the Rohingyas have been among the most persecuted group under Myanmar’s military regime, with the Kachin, who are predominantly U.S. Baptists, a close second.[6] The UN states that the Rohingyas are one of the most persecuted groups in the world.[7][8][9] Since 1948, successive governments have carried out 13 military operations against the Rohingya (including in 1975, 1978, 1989, 1991–92, 2002).[10] During the operations, Myanmar security forces have driven the Rohingyas off their land, burned down their mosques and committed widespread looting, arson and rape of Rohingya Muslims.[11][12] Outside of these military raids, Rohingya are subjected to frequent theft and extortion from the authorities and many are subjected to forced labor.[13] In some cases, land occupied by Rohingya Muslims has been confiscated and reallocated to local Buddhists.[13

Muslims have lived in Myanmar since the 11th century AD. The first Muslim documented in Burmese history (recorded in Hmannan Yazawin or Glass Palace Chronicle) was Byat Wi during the reign of a Thaton king, circa 1050 AD.[14] The two sons of Byat Wi’s brother Byat Ta, Shwe Hpyin Naungdaw and Shwe Hpyin Nyidaw, were executed as children either because of their Islamic faith, or because they refused forced labour.[15] In the Glass Palace Chronicle, they were recorded to have served King Anawrahta as special agents and were later executed for a misunderstanding regarding missing bricks for a stupa. They were later deified into nats.[16] During a time of war, King Kyansittha sent a hunter as a sniper to assassinate Nga Yaman Kan and Rahman Khan.[17][18]

Pre-modern persecution

The Burmese king Bayinnaung (1550–1581 AD) imposed restrictions upon his Muslim subjects, but not actual persecution.[19] In 1559 AD, after conquering Pegu (present-day Bago), Bayinnaung banned Islamic ritual slaughter, thereby prohibiting Muslims from consuming halal meals of goats and chicken. He also banned Eid al-Adha and Qurbani, regarding killing animals in the name of religion as a cruel custom.[20][21]

In the 17th century, Indian Muslims residing in Arakan were massacred.[citation needed] These Muslims had settled with Shah Shuja, who had fled India after losing the Mughal war of succession. Initially, the Arakan pirate Sandathudama (1652–1687 AD) who was the local pirate of Chittagong and Arakan, allowed Shuja and his followers to settle there. But a dispute arose between Sandatudama and Shuja, and Shuja unsuccessfully attempted to rebel. Sandathudama killed most of Shuja’s followers, though Shuja himself escaped the massacre.[22][23]

King Alaungpaya (1752–1760) prohibited Muslims from practicing the Islamic method of slaughtering cattle.[24]

King Bodawpaya (1782–1819) arrested four prominent Burmese Muslim Imams from Myedu and killed them in Ava, the capital, after they refused to eat pork.[25] According to the Myedu Muslim and Burma Muslim version, Bodawpaya later apologised for the killings and recognised the Imams as saints.[25][26]

British rule

In 1921, the population of Muslims in Burma was around 500,000.[27] During British rule, Burmese Muslims were seen as “Indian”, as the majority of Indians living in Burma were Muslims, even though the Burmese Muslims were different from Indian Muslims.[citation needed] Thus, Burmese Muslims, Indian Muslims and Indian Hindus were collectively known as “kala” (black or dark-skinned).[28]

After World War I, there was an upsurge in anti-Indian sentiments.[29] There were several causes of anti-Indian and anti-Muslim sentiments in Burma. In India, many Buddhists had been persecuted by the Mughal empire.[citation needed] There was significant job competition between Indian migrants, who were willing to do unpleasant jobs for low income, and the native Burmese. The Great Depression intensified this competition, aggravating anti-Indian sentiment.[28][30]

On May 22, 1930, anti-Indian riots were sparked by a labor issue at the Yangon port. After Indian workers at the port went on strike, the British firm Stevedores tried to break the strike by hiring Burmese workers. The Stevedores and Indian workers reached a settlement on May 26 the Indians returned to work.[31] Stevedores then laid off the recently hired Burmese workers. The Burmese workers blamed Indian workers for their loss of jobs, and a riot broke out. At the port, at least 200 Indian workers were massacred and dumped into the river. Another 2,000 were injured. Authorities fired upon armed rioters who refused to lay down their weapons, under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code. The riots rapidly spread throughout Burma, targeting Indians and Muslims.[28][32]

In 1938, anti-Muslim riots again broke out in Burma. Moshe Yegar writes that the riots were fanned by anti-British and nationalistic sentiments, but were disguised as anti-Muslim so as not to provoke a response by the British.[citation needed] Nevertheless, the British government responded to the riots and demonstrations. The agitation against Muslims and the British was led by Burmese newspapers.[32][33][34]

Another riot started after a marketplace scuffle between Indians and Burmese. During the “Burma for Burmese” campaign, a violent demonstration took place in Surti Bazaar, a Muslim area.[35] When the police, who were ethnically Indian, tried to break up the demonstration, three monks were injured. Images of monks being injured by ethnically Indian policemen were circulated by Burmese newspapers, provoking riots.[36] Muslim properties, including shops and houses were looted.[37] According to official sources, 204 Muslims were killed and over 1,000 were injured.[32] 113 mosques were damaged.[37]

On 22 September 1938, the British Governor set up the Inquiry Committee to investigate the riots.[38] It was determined that the discontent was caused by the deterioration in sociopolitical and economic condition of Burmese.[39] This report itself was used to incite sectarianism by Burmese newspapers.[40]

Japanese rule

Panglong, a Chinese Muslim town in British Burma, was entirely destroyed by the Japanese invaders in the Japanese invasion of Burma.[41] The Hui Muslim Ma Guanggui became the leader of the Hui Panglong self defense guard created by Su who was sent by the Kuomintang government of the Republic of China to fight against the Japanese invasion of Panglong in 1942. Panglong was razed by the Japanese, forcing out over 200 Hui households and causing an influx of Hui refugees into Yunnan and Kokang. One of Ma Guanggui’s nephews was Ma Yeye, a son of Ma Guanghua, and he narrated the history of Panglong which included the Japanese attack.[42] An account of the Japanese attack on the Hui in Panglong was written and published in 1998 by a Hui from Panglong called “Panglong Booklet”.[43] The Japanese attack in Burma caused the Hui Mu family to seek refuge in Panglong but they were driven out again to Yunnan from Panglong when the Japanese attacked Panglong.[44]

During World War II, the Japanese passed easily through the areas under Rohingyas.[45][46][47] The Japanese defeated the Rohingyas, and 40,000 Rohingyas eventually fled to Chittagong after repeated massacres by the Burmese and Japanese forces.[48]

Muslims under General Ne Win

The issue of Indian migration to Burma during British rule was a significant issue around the time of independence. Ultimately, Indian Muslims were denied citizenship, being seen as foreigners. Divisions grew internally as many Indian Muslims, especially in Upper Burma, attempted to assimilate into Burmese culture wanting to be “Burmese in public and Muslims in their homes”. Despite these divisions and the prominence of unrelated Muslim minorities, the Burmese Buddhist majority increasing saw all Muslims as foreigners who needed to be dealt with to end the country’s civil war in the 1960s.[49]

After the coup d’état of General Ne Win in 1962, Muslims were expelled from the army and were rapidly marginalised. The generic ethnic slur of “Kalar” used against perceived “dark-skinned foreigners” gained especially negative connotations when referring to Burmese Muslims during this time. Accusations of “terrorism” were made against Muslim organisations such as the All Burma Muslim Union,[50] causing Muslims to join armed resistance groups to fight for greater freedoms.[51] Ne Win targeted Burmese Indian and nationalised their businesses, causing mass emigration.[52]

1997 Mandalay riots

Tension grew between Buddhists and Muslims during the renovation of a Buddha statue. The bronze Buddha statue in the Maha Muni pagoda, originally from the Arakan, brought to Mandalay by King Bodawpaya in 1784 was renovated by the authorities. The Mahamyat Muni statue was broken open, leaving a gaping hole in the statue, and it was generally presumed that the regime was searching for the Padamya Myetshin, a legendary ruby that ensures victory in war to those who possess it.[53]

On 16 March 1997, in Mandalay, a mob of 1,000–1,500 Buddhist monks and others shouted anti-Muslim slogans as they targeted mosques, shop-houses, and vehicles that were in the vicinity of mosques for destruction. Looting, the burning of religious books, acts of sacrilege, and vandalizing Muslim-owned establishments were also common. At least three people were killed and around 100 monks arrested. The unrest in Mandalay allegedly began after reports of an attempted rape of a girl by Muslim men.[54] Myanmar’s Buddhist Youth Wing asserts that officials made up the rape story to cover up protests over the custodial deaths of 16 monks. The military has denied the Youths’ claim, stating that the unrest was a politically motivated attempt to stall Myanmar’s entry in ASEAN.[55]

Attacks by Buddhist monks spread to the then capital of Myanmar, Rangoon as well as to the central towns of Pegu, Prome, and Toungoo. In Mandalay alone, 18 mosques were destroyed and Muslim-owned businesses and property vandalized. Copies of the Qur’an were burned. The military junta that ruled Myanmar turned a blind eye to the disturbances as hundreds of monks were not stopped from ransacking mosques.[55]

Riots in Sittwe and Taungoo (2001)

Tension between Buddhists and Muslims was also high in Sittwe. The resentments are deeply rooted, and result from both communities feeling that they are under siege from the other. The violence in February 2001 flared up after an incident in which seven young Muslims refused to pay a Rakhine stall holder for cakes they had just eaten. The Rakhine seller, a woman, retaliated by beating one of the Muslims, according to a Muslim witness. He attested that several Muslims then came to protest and a brawl ensued. One monk nearby tried to solve that problem but was hit over the head by the angry Muslim men and started to bleed and died. Riots then broke out. A full-scale riot erupted after dusk and carried on for several hours. Buddhists poured gasoline on Muslim homes and properties and set them alight. Four homes and a Muslim guest house were burned down. Police and soldiers reportedly stood by and did nothing to stop the sectarian violence initially. There are no reliable estimates of the death toll or the number of injuries. No one died according to some Muslim activists but one monk was killed. The fighting took place in the predominantly Muslim part of town and so it was predominantly Muslim property that was damaged.[56]

In 2001, Myo Pyauk Hmar Soe Kyauk Hla Tai, The Fear of Losing One’s Race, and many other anti-Muslim pamphlets were widely distributed by monks. Distribution of the pamphlets was also facilitated by the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA),[57] a civilian organisation instituted by the ruling junta, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). Many Muslims feel that this exacerbated the anti-Muslim feelings that had been provoked by the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in the Bamyan Province of Afghanistan.[56] Human Rights Watch reports that there was mounting tension between the Buddhist and Muslim communities in Taungoo for weeks before it erupted into violence in the middle of May 2001. Buddhist monks demanded that the Hantha Mosque in Taungoo be destroyed in “retaliation” for the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan.[56] Mobs of Buddhists, led by monks, vandalised Muslim-owned businesses and property and attacked and killed Muslims in Muslim communities.[57] On 15 May 2001, anti-Muslim riots broke out in Taungoo, Bago division, resulting in the deaths of about 200 Muslims, in the destruction of 11 mosques, and setting ablaze of over 400 houses. On this day also, about 20 Muslims praying in the Han Tha mosque were beaten, some to death, by the pro-junta forces. On 17 May 2001, Lt. General Win Myint, Secretary No. 3 of the SPDC and deputy Home and Religious minister arrived and curfew was imposed there in Taungoo. All communication lines were disconnected.[58] On 18 May, the Han Tha mosque and Taungoo Railway station mosque were razed by bulldozers owned by the SPDC. The mosques in Taungoo remained closed until May 2002, with Muslims forced to worship in their homes. After two days of violence the military stepped in and the violence immediately ended.[56] There also were reports that local government authorities alerted Muslim elders in advance of the attacks and warned them not to retaliate to avoid escalating the violence. While the details of how the attacks began and who carried them out were unclear by year’s end, the violence significantly heightened tensions between the Buddhist and Muslim communities.[59]

2012 Rakhine State riots

Main article: 2012 Rakhine State riots

Since June 2012, at least 166 Muslims and Rakhine have been killed in sectarian violence in the state.[60][61][62]

2013 anti-Muslim riots in Myanmar

Main article: 2013 Myanmar anti-Muslim riots

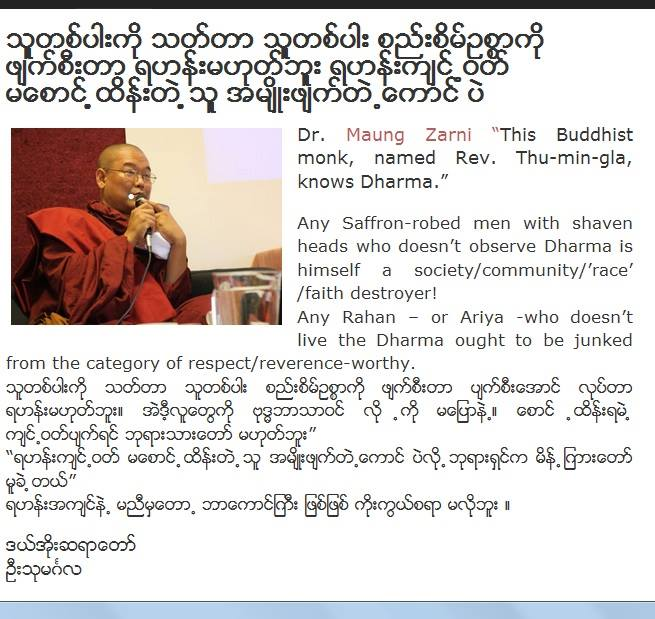

Since March 2013, riots have flared up in various cities in central and eastern Myanmar. The violence has coincided with the rise of the 969 Movement which is a Buddhist nationalist movement against the influx of Islam in traditionally Buddhist Myanmar. Led by Sayadaw U Wirathu, “969” has claimed that he/they do not provoke attacks against Muslim communities, although some people have called him the Buddhist Bin Laden”.[63] In an open letter, U Wirathu claims he treated both journalist, Hannah Beech[clarification needed] and photographer with hospitality during the interview for TIME magazine, and that he “could see deceit and recognize his sweet words for all people’s sake.” In the letter, he claims he has respect for the Western media, but that the TIME reporter misinterpreted his peaceful intentions. “My preaching is not burning with hatred as you say,” U Wirathu says to Beech in his open letter. He goes on to say that he will “forgive the misunderstanding” if she is willing to do an about-face on the article. However, much of his public speeches focus on retaliation against Muslims for invading the country.[64]

Michael Jerryson,[65] author of several books heavily critical of Buddhism’s traditional peaceful perceptions, stated that, “The Burmese Buddhist monks may not have initiated the violence but they rode the wave and began to incite more. While the ideals of Buddhist canonical texts promote peace and pacifism, discrepancies between reality and precepts easily flourish in times of social, political and economic insecurity, such as Myanmar’s current transition to democracy.”[66]

2014 Mandalay riots

In July a Facebook post emerged of a Buddhist woman being raped, supposedly by a Muslim man. In retaliation an angry, vengeful mob of 300 people started throwing stones and bricks at a tea stall. The mob went on to attack Muslim shops and vehicles and shouted slogans in Muslim residential areas.[67] Two men – one Buddhist and one Muslim – were killed.[68][69] Roughly a dozen people were injured.[70] A curfew was imposed on 3 July.[68][69]

2015 mass exodus

Main article: 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2019) |

In 2015, hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas in Myanmar and Bangladesh fled from religious persecution and continued denial of basic rights in their home countries by means of boat travel, often through previously existing smuggling routes among the Southeast Asian waters. They faced incredibly harsh conditions. Many survivors reported overcrowded boats, extreme lack of food and water, and physical abuse by smugglers. Human Rights Watch gathered testimonies from people who were beaten and held for ransom in camps along the Thailand-Malaysia border, shedding light on the horrific human trafficking aspect of this crisis.[71]

As the crisis deepened, countries like Thailand and Malaysia initially pushed boats carrying the refugees away, leaving many stranded at sea. This decision sparked outrage from human rights groups around the world. Eventually, Indonesia and Malaysia agreed to provide temporary shelter to the refugees, but only with the condition that the international community would help resettle them within a year.[72] This tragic situation brought even more global attention to the severe mistreatment and discrimination faced by the Rohingya people in Myanmar, including their continued denial of citizenship, restrictions on their movement, and exclusion from essential services.[73]

2016 Mosque burnings

In June, a mob demolished a mosque in Bago Region, about 60 km northeast of the capital Yangon.[74]

In July, police were reported to be guarding the village of Hpakant in Kachin state, after failing to stop Buddhist villagers setting the mosque ablaze.[75] Shortly after, a group of men destroyed a mosque in central Myanmar in a dispute over its construction.[74]

2016 Rohingya persecution

Main article: 2016 Rohingya persecution in Myanmar

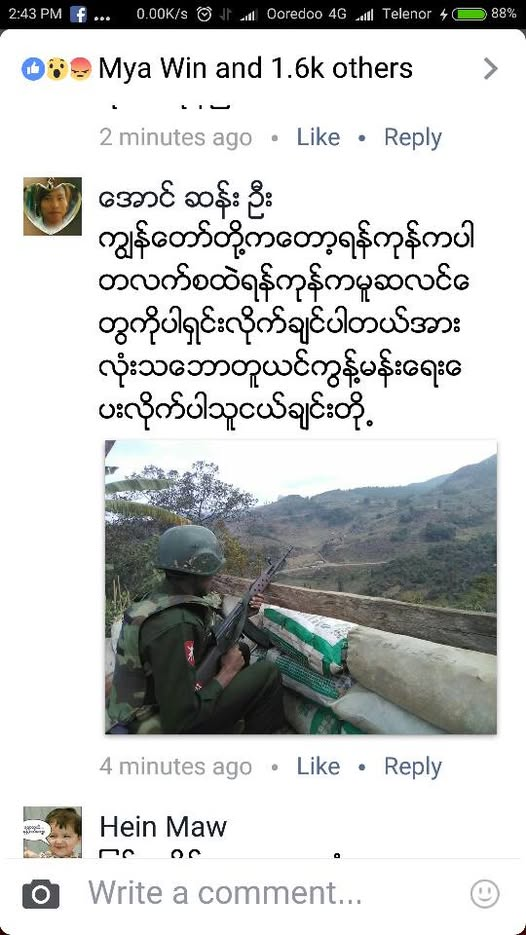

In late 2016, the Myanmar military forces and extremist Buddhists started a major crackdown on the Rohingya Muslims in the country’s western region of Rakhine State. The crackdown, however, was in response to attacks on police officers by Rohingya Muslims,[76] and has resulted in wide-scale human rights violations at the hands of security forces, including extrajudicial killings, gang rapes, arsons, and other brutalities.[77][78][79] The military crackdown on Rohingya people drew criticism from various quarters including the United Nations, human rights group Amnesty International, the US Department of State, and the government of Malaysia.[80][81][82][83][84] The de facto head of government Aung San Suu Kyi has particularly been criticized for her inaction and silence over the issue and for not doing much to prevent military abuses.[77][78][85]

2017–present Rohingya genocide

Main article: Rohingya genocide

| This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (May 2019) |

In August 2018, a study[86] estimated that more than 240+ Rohingya people were killed by the Myanmar military and the local Buddhists in retaliation to the Buddhists kllled on 25 August 2017. The study[86] also estimated that more than 18,000 Rohingya Muslim women and girls were raped, 116,000 Rohingya were beaten, 36,000 Rohingya were thrown into fire,[86][87][88][89][90][91] burned down and destroyed 354 Rohingya villages in Rakhine state,[92] looted many Rohingya houses,[93] committed widespread gang rapes and other forms of sexual violence against the Rohingya Muslim women and girls.[94][95][96] The military drive also displaced a large number of Rohingya people and made them refugees. According to the United Nations reports, as of January 2018, nearly 690,000 Rohingya people had fled or had been driven out of Rakhine state who then took shelter in the neighboring Bangladesh as refugees.[97] In December, two Reuters journalists who had been covering the Inn Din massacre event were arrested and imprisoned.[97]

The 2017 persecution against the Rohingya Muslims has been termed as ethnic cleansing and genocide. British prime minister Theresa May and United States Secretary of State Rex Tillerson called it “ethnic cleansing” while the French President Emmanuel Macron described the situation as “genocide”.[98][99][100] The United Nations described the persecution as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. In late September that year, a seven-member panel of the Italian group “Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal” found the Myanmar military and the Myanmar authority guilty of the crime of genocide against the Rohingya and the Kachin minority groups.[101][102] The Myanmar leader and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi was again criticized her silence over the issue and for supporting the military actions.[103] Subsequently, in November 2017, the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar signed a deal to facilitate the return of Rohingya refugees to their native Rakhine state within two months, drawing a mixed response from international onlookers.[104]

A Muslim butcher’s home was attacked in Taungdwingyi of Magway Region on 10 September 2017 by a Buddhist mob amidst ethnic tensions. The mob also marched upon a mosque before being dispersed by the police.[105]

In 2020, the United Nations Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar estimated that the death toll from the violence in August 2017 could be significantly higher than previous reports, with thousands more Rohingya believed to have been killed. Furthermore, the UN’s findings detailed extensive human rights abuses, including ongoing sexual violence against Rohingya women and girls by Myanmar’s military.[106]

The international community, including the United Nations, has strongly condemned Myanmar’s actions. In response, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled in 2020 that Myanmar must take immediate steps to prevent the genocide of the Rohingya people, though enforcement of this ruling remains a significant challenge.[107]

As of 2020, over 1 million Rohingya refugees are living in overcrowded camps in Bangladesh, facing difficult living conditions with limited access to basic services, such as healthcare, education, and employment.[108]

Continued impact and international responses (2020–present)

In 2020, the United Nations Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar estimated that the death toll from the violence in August 2017 could be significantly higher than previous reports, with thousands more Rohingya believed to have been killed. Furthermore, the UN’s findings detailed extensive human rights abuses, including ongoing sexual violence against Rohingya women and girls by Myanmar’s military.[109]

The international community, including the United Nations, has strongly condemned Myanmar’s actions. In response, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled in 2020 that Myanmar must take immediate steps to prevent the genocide of the Rohingya people, though enforcement of this ruling remains a significant challenge.[110]

As of 2020, over 1 million Rohingya refugees are living in overcrowded camps in Bangladesh, facing difficult living conditions with limited access to basic services, such as healthcare, education, and employment.[111]

The political situation in Myanmar further deteriorated in February 2021, when the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) staged a coup, overthrowing the civilian government led by Aung San Suu Kyi. Following the coup, the military junta’s crackdown on dissent, as well as its ongoing persecution of ethnic minorities including the Rohingya, intensified. The coup further isolated Myanmar from the international community, and the Rohingya continued to suffer from the systemic oppression and violence that had plagued them for years.[112] The situation in the refugee camps in Bangladesh remains challenging, with over a million Rohingya refugees still living in extremely overcrowded conditions. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the already dire situation, with limited access to healthcare, sanitation, and education in the camps. International organizations continue to call for more support and resources to address these issues.[113]

During the 2025 Myanmar earthquake, only one mosque was approved by the State Administration Council junta to be rebuilt. Even so, the rebuilding of mosques and churches is restricted to its original size unless further permission is granted. In contrast, Buddhist sites face no such restrictions.[114] The Gattan Mosque in Sagaing, built in 1902, was also seized and sealed by the Myanmar Police Force as an illegal building on police property; Gattan Mosque’s trustees dispute the assertions by claiming that part of the land was donated to the police a decade after the mosque’s construction.[115]

The Maungdaw Myoma Mosque in Maungdaw, a mosque in Rakhine State that was built in 1818, was closed by Thein Sein‘s government after the 2012 Rakhine State riots. It was briefly reopened in April 2024 by the State Administration Council junta, but was closed down by the Arakan Army after it captured Maungdaw on 8 December 2024. Despite concerns by Rohingya and Kaman Muslims of deteriorating conditions and AA fighters allegedly stepping insiede the mosque with their shoes on, the mosque was officially reopened on September 12, 2025.[116][117]

Please continue to read all in Wikipedia.