1. Loss of Royal Patronage

- Buddhism depended heavily on support from kings like Ashoka, Kanishka, and regional dynasties.

- When later Hindu rulers (Guptas, post-Gupta kingdoms) shifted patronage back to Brahmanism/Hinduism, Buddhist monasteries declined.

2. Monastic Wealth and Weakening of the Sangha

- Large monasteries became wealthy and sometimes complacent.

- Fewer monks practiced strict discipline.

- Public respect decreased, and Buddhism lost its earlier missionary energy.

3. Revival and Reform Within Hinduism

- Hinduism “absorbed” many Buddhist ideas: compassion, non-violence, monasticism, logic, etc.

- Reform movements like Advaita Vedanta and Bhakti revived Hinduism with simpler, more emotional worship appealing to the masses.

- Many Buddhist communities gradually merged back into Hindu society.

4. Sanskritization and Social Factors

- Buddhism challenged caste, but later Buddhist societies re-adopted caste structures.

- Brahmin intellectual dominance re-established itself and re-won the support of many local elites.

5. Destruction of Monasteries During Medieval Turmoil

Major monastic universities like Nalanda, Vikramashila, and Odantapuri were destroyed in the 12th–13th centuries.

- Thousands of monks fled to Tibet and Nepal.

- This did not “cause” the decline, but it accelerated the final collapse, because the remaining institutions were physically wiped out.

6. Shift in Trade Routes

- Many monasteries depended on trade guilds and Silk Road routes.

- When trade patterns changed, monasteries lost income and sustenance.

7. Lingering Survival in the East

- Buddhism did not entirely vanish; only its strong institutional presence disappeared.

- Small Buddhist communities survived in Bengal, Orissa, Kashmir, and the Himalayas until the 19th century.

In Summary

- Primary causes: Loss of patronage, internal weakening, absorption by a revitalized Hinduism.

- Secondary but important cause: Destruction of monasteries.

- Result: Buddhism declined gradually over centuries; it didn’t disappear overnight or due to one religion.

အိန္ဒိယတိုက်တွင် ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ ပျောက်ကွယ်သွားရသည့် အကြောင်းရင်းများ (အကျဉ်းချုပ်)

က။ ဘုရင်များ၏ အားပေးထောက်ခံမှု လျော့နည်းသွားခြင်း

ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာသည် အာသောက၊ ကနီရှကာ စသော ဘုရင်များ၏ အားပေးမှုအပေါ် အလွန်မူတည်ခဲ့သည်။ နောက်ပိုင်း ဂုပတ မင်းဆက်နှင့် ထို့နောက် မင်းဆက်များက ဗြဟ္မဏဝါဒ/ဟိန္ဒူဘာသာကို ပြန်လည်အားပေးလာသောအခါ ဘုန်းတော်ကြီးကျောင်းများ တဖြည်းဖြည်း ကျဆင်းလာ။

ခ။ သံဃာအဖွဲ့ အတွင်းပိုင်း အားနည်းလာခြင်း

ကြီးမားသော ဘုန်းတော်ကြီးကျောင်းများ စည်းစိမ်ကြွယ်ဝလာပြီး စည်းကမ်းတင်းကျပ်မှု လျော့နည်းသွားသည်။ သံဃာအချို့၏ ဘာသာရေးတရားထိုင် ဟောကြား သင်ပြ မှု လျော့နည်းလာသဖြင့် လူထု၏ လေးစားမှုလည်း လျော့နည်းကာ မျိုးဆက်သစ်သို့ ဖြန့်ဝေရန် အင်အားလည်း နည်းလာ။

ဂ။ ဟိန္ဒူဘာသာ၏ ပြန်လည်အသက်ဝင်လာခြင်း

ဟိန္ဒူဘာသာသည် ကရုဏာ၊ အဟိံသ၊ သံဃာစနစ်၊ အယူအဆဆိုင်ရာ အမြင်များ စသည့် ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ အယူအဆများကို ထည့်သွင်းလက်ခံခဲ့သည်။ ဗုဒ္ဓရုပွါးတော်ကို ဟိန္ဒူဘုရာစင်ပေါ်တင် ကိုးကွယ်စေပြီး ကိုးကွယ်စေခြင်းဖြင့် တန်းညှိသိက္ခာချခဲ့သည်။ ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာဝင်အချို့ကို ဟိန္ဒူဘာသာဘက်သို့ အောင်မြင်စွာ ပြန်လည်ဆွဲဆောင်ခဲ့ကြသည်။ ဗအဒ္ဝိုင်တ ဝေဒန္တ၊ ဘက်ခတီ လှုပ်ရှားမှုများကြောင့် လူထုအတွက် ပိုမိုလွယ်ကူ၊ စိတ်ခံစားမှုအခြေပြု ဘာသာရေးဖြစ်လာကာ ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာဝင် အချို့သည် ဟိန္ဒူလူမှုအသိုင်းအဝိုင်းထဲသို့ တဖြည်းဖြည်း ပေါင်းစည်းသွား။

ဃ။ လူမှုရေးနှင့် ဘာသာရေး ပြောင်းလဲမှုများ

ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာသည် ဇာတ်ခွဲခြားမှုကို ဆန့်ကျင်ခဲ့သော်လည်း နောက်ပိုင်း ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ အသိုင်းအဝိုင်းများတွင်လည်း ဇာတ်စနစ် ပြန်လည်ပေါ်ပေါက်လာသည်။ ဗြဟ္မဏ ပညာရှင်များ၏ ဦးဆောင်မှု ပြန်လည်ခိုင်မာလာပြီး ဒေသခံ အထက်တန်းလူမျိုးများ၏ ထောက်ခံမှုကို ပြန်လည်ရရှိခဲ့သည်။

င။ အလယ်ခေတ် အရေးအခင်းများကြောင့် ဘုန်းတော်ကြီးကျောင်းများ ပျက်စီးခြင်း

၁၂–၁၃ ရာစုများတွင် နာလန္ဒာ၊ ဝိက္ခရမရှီလာ၊ ဩဒန္တပူရီ စသော ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ တက္ကသိုလ်ကြီးများ ဖျက်ဆီးခံရပြီး သံဃာအများအပြားသည် တီဘက်နှင့် နီပေါသို့ ထွက်ပြေးခဲ့ရသည်။ ယင်းအကြောင်းရင်းသည် ပျောက်ကွယ်မှု၏ အဓိကအကြောင်းမဟုတ်သော်လည်း နောက်ဆုံးအဆင့်ကို မြန်ဆန်စေ။

စ။ ကုန်သွယ်ရေးလမ်းကြောင်း ပြောင်းလဲခြင်း

ဘုန်းတော်ကြီးကျောင်းများစွာသည် ကုန်သွယ်ရေးအဖွဲ့များနှင့် ဆိုင်ကမ်းလမ်းကြောင်းများအပေါ် မူတည်နေရာ ကုန်သွယ်ရေး ပုံစံပြောင်းလဲသွားသောအခါ အထောက်အပံ့ လျော့နည်းသွား။

ဆ။ အရှေ့ဘက်ဒေသများတွင် ဆက်လက်တည်ရှိနေခြင်း

ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာသည် လုံးဝပျောက်ကွယ်သွားခြင်းမဟုတ်ဘဲ အဖွဲ့အစည်းကြီးများသာ ပျောက်ကွယ်သွားခဲ့သည်။ ဘင်္ဂါလ၊ အိုရစ်ဆာ၊ ကက်ရှမီးယားနှင့် ဟိမဝန္တာ ဒေသများတွင် ၁၉ ရာစုအထိ အသေးစား အသိုင်းအဝိုင်းများ ဆက်လက်တည်ရှိခဲ့သည်။

အကျဉ်းချုပ်

အဓိကအကြောင်းရင်းများမှာ ဘုရင်များ၏ အားပေးမှု လျော့နည်းခြင်း၊ သံဃာအဖွဲ့ အားနည်းလာခြင်းနှင့် ပြန်လည်အသက်ဝင်လာသော ဟိန္ဒူဘာသာထဲသို့ ပေါင်းစည်းသွားခြင်း ဖြစ်သည်။ ဘုန်းတော်ကြီးကျောင်းများ ဖျက်ဆီးခံရခြင်းသည် အရေးကြီးသော်လည်း ဒုတိယအဆင့် အကြောင်းရင်းဖြစ်ပြီး ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာသည် ရာစုနှစ်များအတွင်း တဖြည်းဖြည်း ကျဆင်းသွားခြင်းသာ ဖြစ်သည်။

From Wikipedia:

Gupta Empire (4th–6th century)

Religious developments

During the Gupta Empire (4th to 6th century), Vaishnavism, Shaivism and other Hindu sects became increasingly popular, while Brahmins developed a new relationship with the state. The differences between Buddhism and Hinduism blurred, as Mahayana Buddhism adopted more ritualistic practices, while Buddhist ideas were adopted into Vedic schools.[12] As the system grew, Buddhist monasteries gradually lost control of land revenue. In parallel, the Gupta kings built Buddhist temples such as the one at Kushinagara,[13][14] and monastic universities such as those at Nalanda, as evidenced by records left by three Chinese visitors to India.[15][16][17]

Hun invasions (6th century)

Chinese scholars travelling through the region between the 5th and 8th centuries, such as Faxian, Xuanzang, Yijing, Hui-sheng, and Song Yun, began to speak of a decline of the Buddhist sangha in the northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, especially in the wake of the Hun invasion from central Asia in the 6th century CE. Xuanzang wrote that numerous monasteries in northwestern India had been reduced to ruins by the Huns.[18][19]

Mihirakula, the Alchon Hun ruler who ruled in the northwestern region (modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north India) from 515–540 CE, was known for his persecution of Buddhists.[20] He ordered the expulsion of monks and the destruction of many Buddhist monasteries throughout Gandhara, and even as far away as modern-day Prayagraj.[21] Between 525 and 532 CE, Yashodharman (ruler of the Malava Empire) and rulers of the Gupta Empire reversed Mihirakula’s campaign and ended the Mihirakula era.[22][23]

The religion recovered slowly from these invasions during the 7th century, with the “Buddhism of Punjab and Sindh remaining strong”. The reign of the Pala Dynasty (8th to 12th century) saw Buddhism in North India recover due to royal support from the Palas, who supported various Buddhist centers like Nalanda. By the eleventh century, Pala rule had weakened, however.[24]

Socio-political change and religious competition

The regionalisation of India after the end of the Gupta Empire (320–650 CE) led to the loss of patronage and donations.[26] The prevailing view of decline of Buddhism in India is summed by A. L. Basham‘s classic study which argues that the main cause was the rise of an ancient Hindu religion again, “Hinduism“, which focused on the worship of deities like Shiva and Vishnu and became more popular among the common people while Buddhism, being focused on monastery life, had become disconnected from public life and its life rituals, which were all left to Hindu Brahmins.[citation needed]

Religious competition

See also: Buddhism and Hinduism

The growth of new forms of Hinduism (and to a lesser extent Jainism) was a key element in the decline in Buddhism in India, particularly in terms of diminishing financial support to Buddhist monasteries from laity and royalty and also not having any support of kings .[27][28][29] According to Kanai Hazra, Buddhism declined in part because of the rise of the Brahmins and their influence in socio-political process.[30] According to Randall Collins, Richard Gombrich and other scholars, Buddhism’s rise or decline is not linked to Brahmins or the caste system, since Buddhism was “not a reaction to the caste system”, but aimed at the salvation of those who joined its monastic order.[31][32][33]

The disintegration of central power also led to regionalisation of religiosity, and religious rivalry.[34] Rural and devotional movements arose within Hinduism, along with Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Bhakti and Tantra,[34] that competed with each other, as well as with numerous sects of Buddhism and Jainism.[34][35] This fragmentation of power into feudal kingdoms was detrimental for Buddhism, as royal support shifted towards other communities and Brahmins developed a strong relationship with Indian states.[26][36][27][28][29][30]

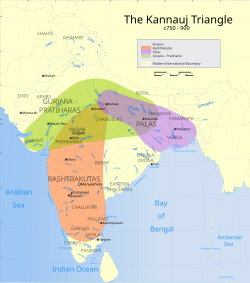

Over time the new Indian dynasties which arose after the 7th and 8th centuries tended to support Hinduism, and this conversion proved decisive. These new dynasties, all of which supported Hinduism, include “the Karkotas and Pratihara Rajputs of the north, the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan, and the Pandyas and Pallavas of the south” (the Pala Dynasty is one sole exception to these).[citation needed] One of the reasons of this conversion was that the Brahmins were willing and able to aid in local administration, and they provided councillors, administrators and clerical staff.[37] Moreover, Brahmins had clear ideas about society, law and statecraft (and studied texts such as the Arthashastra and the Manusmriti) and could be more pragmatic than the Buddhists, whose religion was based on monastic renunciation and did not recognise that there was a special warrior class that was divinely ordained to use violence justly.[38] As Johannes Bronkhorst notes, Buddhists could give “very little” practical advice in response to that of the Brahmins, and Buddhist texts often speak ill of kings and royalty.[39]

Bronkhorst notes that some of the influence of the Brahmins derived from the fact that they were seen as powerful, because of their use of incantations and spells (mantras) as well as other sciences like astronomy, astrology, calendrics and divination. Many Buddhists refused to use such “sciences” and left them to Brahmins, who also performed most of the rituals of the Indian states (as well as in places like Cambodia and Burma).[40]

Lars Fogelin argues that the concentration of the sangha into large monastic complexes like Nalanda was one of the contributing causes for the decline. He states that the Buddhists of these large monastic institutions became “largely divorced from day-to-day interaction with the laity, except as landlords over increasingly large monastic properties”.[41] Padmanabh Jaini also notes that Buddhist laypersons are relatively neglected in the Buddhist literature, which produced only one text on lay life and not until the 11th century, while Jains produced around fifty texts on the life and conduct of a Jaina layperson.[42]

These factors all slowly led to the replacement of Buddhism in the South and West of India by Hinduism and Jainism. Fogelin states that

While some small Buddhist centers still persisted in South and West India in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, for the most part, both monastic and lay Buddhism had been eclipsed and replaced by Hinduism and Jainism by the end of the first millennium CE.[43]

Buddhist sources also mention violence against Buddhists by Hindu Brahmins and kings. Hazra mentions that the eighth and ninth centuries saw “Brahminical hostilities towards Buddhism in South India”[44]

Religious convergence and absorption

Buddhism’s distinctiveness also diminished with the rise of Hindu sects. Though Mahayana writers were quite critical of Hinduism, the devotional cults of Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism likely seemed quite similar to laity, and the developing Tantrism of both religions were also similar.[45] Also, “the increasingly esoteric nature” of both Hindu and Buddhist tantrism made it “incomprehensible to India’s masses”, for whom Hindu devotionalism and the worldly power-oriented Nath Siddhas became a far better alternative.[46][47][note 1] Buddhist ideas, and even the Buddha himself,[48] were absorbed and adapted into orthodox Hindu thought,[49][45][50] while the differences between the two systems of thought were emphasised.[51][52][53][54][55][56]

Elements which medieval Hinduism adopted during this time included vegetarianism, a critique of animal sacrifices, a strong tradition of monasticism (founded by figures such as Shankara) and the adoption of the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu.[57] On the other end of the spectrum, Buddhism slowly became more and more “Brahmanized”, initially beginning with the adoption of Sanskrit as a means to defend their interests in royal courts.[58] According to Bronkhorst, this move to the Sanskrit cultural world also brought with it numerous Brahmanical norms which now were adopted by the Sanskrit Buddhist culture (one example is the idea present in some Buddhist texts that the Buddha was a Brahmin who knew the Vedas).[59] Bronkhorst notes that with time, even the caste system eventually became widely accepted for “all practical purposes” by Indian Buddhists (this survives among the Newar Buddhists of Nepal).[60] Bronkhorst notes that eventually, a tendency developed in India to see Buddhism’s past as having been dependent on Brahmanism and secondary to it. This idea, according to Bronkhorst, “may have acted like a Trojan horse, weakening this religion from within”.[61]

The political realities of the period also led some Buddhists to change their doctrines and practices. For example, some later texts such as the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra and the Sarvadurgatipariśodhana Tantra begin to speak of the importance of protecting Buddhist teachings and that killing is allowed if necessary for this reason. Later Buddhist literature also begins to see kings as bodhisattvas and their actions as being in line with the dharma (Buddhist kings like Devapala and Jayavarman VII also claimed this).[62] Bronkhorst also thinks that the increase in the use of apotropaic rituals (including for the protection of the state and king) and spells (mantras) by 7th century Indian Buddhism is also a response to Brahmanical and Shaiva influence. These included fire sacrifices, which were performed under the rule of Buddhist king Dharmapala (r. c. 775–812).[63] Alexis Sanderson has shown that Tantric Buddhism is filled with imperial imagery reflecting the realities of medieval India, and that in some ways work to sanctify that world.[64] Perhaps because of these changes, Buddhism remained indebted to the crept in Brahmanical thought and practice now that it had adopted much of its world-view. Bronkhorst argues that these somewhat drastic changes “took them far from the ideas and practices they had adhered to during the early centuries of their religion, and dangerously close to their much-detested rivals.”[65] These changes which brought Buddhism closer to Hinduism, eventually made it much easier for it to be absorbed into Hinduism and lose its separate identity for them.[45]

Patronage

In ancient India, regardless of the religious beliefs of their kings, states usually treated all the important sects relatively even-handedly.[9] This consisted of building monasteries and religious monuments, donating property such as the income of villages for the support of monks, and exempting donated property from taxation. Donations were most often made by private persons such as wealthy merchants and female relatives of the royal family, but there were periods when the state also gave its support and protection. In the case of Buddhism, this support was particularly important because of its high level of organisation and the reliance of monks on donations from the laity. State patronage of Buddhism took the form of land grant foundations.[66]

Numerous copper plate inscriptions from India as well as Tibetan and Chinese texts suggest that the patronage of Buddhism and Buddhist monasteries in medieval India was interrupted in periods of war and political change, but broadly continued in Hindu kingdoms from the start of the common era through the early first millennium CE.[67][68][69] The Gupta kings built Buddhist temples such as the one at Kushinagara,[70][14] and monastic universities such as those at Nalanda, as evidenced by records left by three Chinese visitors to India.[15][16][17]

Internal social-economic dynamics

According to some scholars such as Lars Fogelin, the decline of Buddhism may be related to economic reasons, wherein the Buddhist monasteries with large land grants focused on non-material pursuits, self-isolation of the monasteries, loss in internal discipline in the sangha, and a failure to efficiently operate the land they owned.[69][71] With the growing support for Hinduism and Jainism, Buddhist monasteries also gradually lost control of land revenue.

Re-assessing impact of invasions

See also: Conversion of Buddhist sites into Hindu temples

However, according to some scholars, fresh re-assessments of evidence from archaeology[92] in addition to historical records[93] have disputed this view of Muslim invasions as the major cause of the decline of Buddhism in India or the destruction of Buddhist sites — arguing, instead, “that Brahmanical hostility toward Buddhists resulted in the destruction of Sarnath and other sites”.[94] According to archaeologist Giovanni Verardi: “Contrary to what is usually believed, the great monasteries of Gangetic India, from Sarnath to Vikramaśīla, from Odantapurī to Nālandā, were not destroyed by the Muslims, but appropriated and transformed by the Brahmans with only the occasional intervention of the Muslim forces”.[92] According to Verardi, “orthodox” Brahmins — who had been gaining in power and influence during the Gahadavala (11th-12th c.) and Sena dynasties (11th-12th c.), the rival Hindu-revivalist dynasties of northern/eastern India — “accepted Muslim rule in exchange for the extirpation of Buddhism and the repression of the social sectors in revolt.”[92] Archaeologist Federica Barba writes that the Gahadavala Rajputs built large Hindu temples in traditional Buddhist sites such as Sarnath, and converted Buddhist shrines into Brahmanical ones: Evidence indicates that Buddhists had been expelled from Sarnath during the mid 12th-century, under the Gahadavala rule, and it already was in the process of being converted to a large Shiva temple compound before Muslim invaders arrived.

Conversion of Buddhist temples into Hindu temples

See also: Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent

| Current Name | Buddhist Structure | Images | City | Country | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sri Sanni Siddheswara temple | Krishna, AP | India | Up to 11 Hindu temples have been built on Buddhist sites in the villages of Machilipatnam and Nidumolu, in the Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh. The buildings were converted into Hindu temples by the Chalukya folk.[39] | ||

| Kachchi Kuti | Kushan-era stupas, identified as the Anathapindika (or Sudatta) Stupa | Sravasti, UP | India | The earliest structures of Kachchi Kuti, which were Buddhist, date to the Kushan period; over which a Brahmanical temple with terracotta panels depicting scenes from the Ramayana was constructed during the Gupta period.[40][41][42] | |

| Bhuteshwar Temple | Mathura, UP | India | Anti-caste scholars argue that this temple was built on a site of a Buddhist structure.[43][44] | ||

| Gokarneshwar Temple | Mathura, UP | India | Anti-caste scholars argue that this temple was built on a site of a Buddhist structure.[43][44] | ||

| Badrinath Temple | Badrinath, Uttarakhand | India | Originally a shrine during the Vedic Period, it is believed that it was converted to Buddhist shrine during the Ashoka’s reign. It remained as such until the 8th century when Adi Shankara revived the shrine and converted it to a Hindu temple.[45][46] |