Aman Ullah

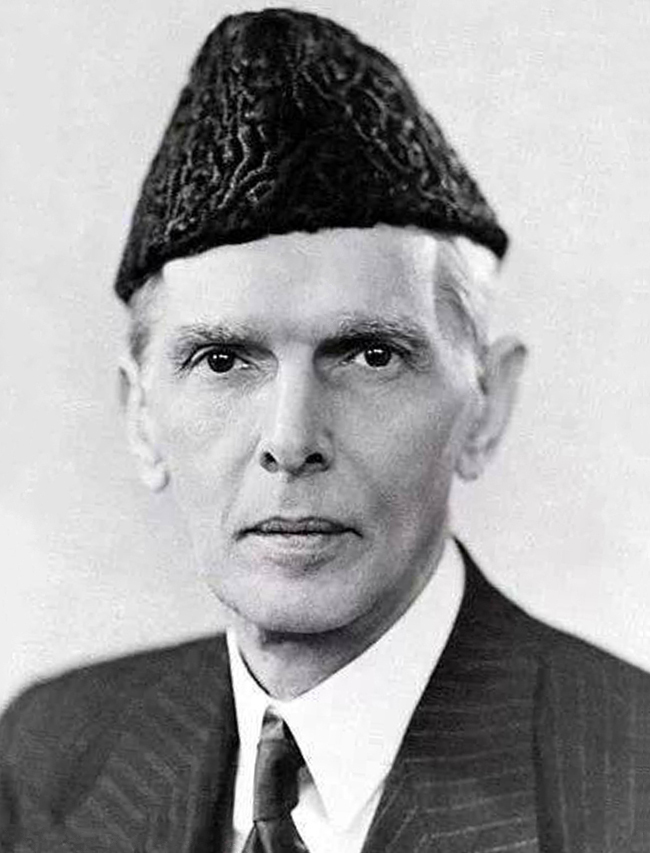

Why the Rohingya Went to Mr. Jinnah of Pakistan

On the eve of independence, in late 1940, Burmese nationalists elected to sustain the colonial racial divisions created some 60 years earlier in the post-colonial settlement. Further widening of racial and ethnic conflict occurred during the Second World War. That war saw the Burman majority and “Rakhine” Buddhists supporting the Japanese, and fighting Karen, Chin, Shan, Kachin and Muslim groups who were variously supported by the British, Americans and Chinese. As a result, Myanmar/Burma faced independence in 1948 as a deeply divided society.

The Burma Campaign (1941-45), often hailed as the “forgotten war,” not merely brought international geopolitics at the doorstep of British India but also transformed the Muslims of Arakan into willful strategic players. With two colonial powers locking horns in Burma — Japan promising independence and Britain struggling to retain control of its crown colony — the Muslims of Arakan cooperated with the British in the hope that they would be granted administrative autonomy. After the British retreat in early 1942, the northern Arakan region erupted in retributive communal violence against pro-British Muslims of Arakan perpetrated by the pro-Japanese Buddhist population. During the three British-led Arakan Campaigns, the Arakan Muslims were recruited as part of the “V Force” — the wartime British intelligence-gathering guerrilla group— against the Japanese.

In postwar British Burma, the colonial rulers conferred on the Muslims of Arakan significant administrative posts in Arakan as reward for their wartime participation in the British military efforts against the Japanese. The Arakan Muslims leaders used their newly found positions of leverage to seek administrative autonomy, but in vain. As the Partition of British India loomed large, the Rohingyas hoped to join the future Muslim-majority province of East Pakistan.

In July 1947, a delegation of the Muslims of Arakan met with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the soon-to-be founding president of Pakistan, in Karachi. They appealed Jinnah either to include the Muslim-dominant areas of northern Rakhine into what would become East Pakistan or to pressurize the Burman leader Aung San to grant autonomy to the Muslims of north Arakan. Before Jinnah met this delegation, he had already met Mr. Rashid, a special envy of Aung San, who assured Mr. Jinnah on behalf of Aung San that the rights of Arakan Muslims shall be constitutionally guaranteed. Jinnah refused to interfere in what he considered the internal affairs of Burma but assured the Muslims delegation that they had nothing to worry as he was convinced of the promise given to him by Aung San about the future of the Arakan Muslims.

Demanding or trying by the Muslims of Arakan an autonomous state within newly independent Burma was a direct response to insecurity felt within the Muslim population in the aftermath of the Second World War. Arakanese Muslims believed at that time that they would be better off under Pakistani or autonomous rule than other thing.

However, it was not the Muslims of Arakan not alone, the Rakhines also tried in many times and in many ways.

• In 1824, the Rakhine made an agreement with British known as Arakan-British Agreement (1824). It was signed by Commissioner De Cean and Mayor Thomas Robertson on behalf of British crown and Prince Hwree Ban, Mayor Aung Kyaw Zan and Dewan Gri Aung Kyaw Hrwee on behalf of Aran. The main points of agreement were i) Rakhine people would fight at the British side in the First Anglo-Burma war, ii) Arakan will be ruled by Rakhines while the British stayed as overlord. However, the British simply ignored the agreement and the three Rakhine leaders sought help from French to rebel against the British. They were captured and imprisoned in Dhaka Jail where they undertook hunger strike unto death. [1]

• According to the Telegram dated 16/05/1947, sent by the Chief Secretary of the Government of Burma to the Secretary of State for Burma, Rakhine leader U Hla Htoon Pru and some Rakhine prominent leaders in Rangoon were trying to hold a meeting for the demand of Arakanistan.[2]

• From 1-3 April an all-Arakan Conference, attended by 7,000 delegates and watch by as estimated 60, 000-stron crowd, was called by U Seinda and Bonbouk Tha Kyaw. British Intelligence reports confirm eyewitness accounts that the crowd shouted slogans not only against the British, the elections, the police and the army but also against Aung San, the popular cry now was for revolution for Arakasn’s independent, [3] U Seinda was for recognition of the historical independence of Arakan and not unreasonably, for the immediate formation of an autonomous Arakan state with the same rights as the Han and Kachins. [4]

• According to the 3 June 1947, Reuters Report, “The trouble in Arakan is essentially a rebellion for the separation of Arakan, but the Communist agitators and dacoit bands have infiltrated into the movement”. [5] Against the troubled backdrop, a fast-growing campaign by Muslim Activities for the creation of an Islamic ‘frontier state’ in the Muslim majority district of north Arakan was completely lost sight of. [6]

• Even, in 1989, according to Shwe Lu Maung, NUFA Chairman Kyaw Hlaing approached the Indian authorities to grant NUFA territorial access within India, with a political office in Culcutta and New Delhi and worked out a strategic Plan with the option of Arakan State in the Republic of India. [7]

This was not only the Muslims of Arakan (Rohingya) and Rakhine alone rather all other ethnic nationalities also try on their own ways. These have been a historical bone of contention like other issues such as a federal versus a unitary Burma.

The ethnic Rohingya is one of the many nationalities of the union of Burma. And they are one of the two major communities of Arakan; the other is Rakhine and Buddhist. The Muslims (Rohingyas) and Buddhists (Rakhines) peacefully co-existed in the Arakan for many centuries. In addition to Muslim (Rohingya) and Buddhist (Rakhine) majority groups, a number of other minority peoples also come to live in Arakan, including the Chin, Kamans, Thet, Dinnet, Mramagri, Mro and Khami who, though many are Christians today, were traditionally animists. The Kamans are Muslims and the Mramagri (Baurwa) are Buddhists. Some ethnic Burman also comes to live in Arakan since 1784 after invasion and occupation by the Burman.

Since Burmese independence in 1948, the Rohingyas have been struggling for their right of self-determination upholding the principle of peaceful co-existence within Burmese federation. They have long been trying to identify themselves with the Union of Burma on the basis of equality and justice. They think that the individual right is not enough for them; they need their collective rights as a people, as an ethnic group, as a nationality who speak different language, who practice different culture, who worship different religion and who also has different historical background and, above all, all of us have territorially clearly defined homelands and nations since time immemorial.

That’s why they want to rule their homeland by themselves They are trying to find a political and legal system which will allow them to rule their respective homelands by themselves, and at same time living peacefully together with others who practice different religions and cultures and speak different languages. In other words, they are trying to find a political system which can combine and balance between “self-rule” for different ethnic groups and “shared-rule” for all the peoples in the Union of Burma.

For this reason, the Muslims of Arakan rendered their support to the British against the Japanese occupation in order to strengthen their standing in the region and encourage Muslim loyalty, the British had published a declaration granting them the status of a Muslim National Area. This entire area was re-conquered by the British at the beginning of 1945. The British set up Peace Committees and organized civilian administrations which functioned until Burma was granted independence in January, 1948. Most of the office-holders were local Muslims, Rohingya, who had previously cooperated with the British.

The principal political effect of the ‘Peace Committee of North Arakan’ was that it made the Muslims of Arakan autonomy conscious. The promise of British to create a Muslim national area doubled their desire for Muslim state. However, when the demand of Muslim State was put to Rees William Commission, the result was not good.

For this consciousness they went to Mohammed Ali Jinnah in 1947 either to fight for including north Arakan within Pakistan or pressurize General Aung San to grant autonomy to the Muslims of north Arakan. To form an autonomous Muslim State, they took arms and was demanded “To form an autonomous Muslim State in north Arakan, comprising Buthidaung, Rathedaung and Maungdaw townships from the west of Kaladan River up to the eastern part of the Naf River that will remain under the Union of Burma.”

For this reason, they joined hands with Arakanese Communist Party led by U Tun Aung Pru to fight together until the fall of the AFPFL’s government with the understanding that Muslims would take the western side of Kaladan whereas the rest of Arakan would be under the control of Arakan Communist Party.

For this reason, they took arms and demanded that all the injustices against the Muslims of Arakan be corrected and that they be allowed to live as Burmese citizens, according to the law, and not be subject to arbitrariness and tyranny.

For this reason, the Muslims objected to the demand of the Arakan Party for the status of a state for Arakan within the framework of the Union of Burma. The large majority of the Muslim organizations of the Rohinga of Maungdaw and Buthidaung demanded autonomy for the region, to be directly governed by the central government in Rangoon without any Arakanese officials or any Arakanese influence whatsoever. Their minimal demand was the creation of a separate district without autonomy but governed from the center. The Muslim members of the Constituent Assembly, and later the Muslim M. P’s from Arakan raised this demand also during the debates in Parliament and in the press.

In the years 1960 to 1962, the Rohingya organizations and the respective Arakanese Muslim organizations initiated frantic activities with reference to the Muslim status in Arakan, and especially in the regions of Maungdaw and Buthidaung. This was in response to the promise made by U Nu on the eve of the general elections of 1960, that if his party won, he would confer the status of a “State” upon Arakan, within the framework of the Union of Burma, on a par with the “statehood” of the other integral states of the Union. After winning the elections, U Nu appointed an enquiry commission to study all the problems involved in the question of Arakan.

The Rohinga Jamiyyat al-‘Ulama’ submitted to this enquiry commission a long and explanatory memorandum on the position of the Muslims of northern Arakan. The memorandum stated that the Muslims of this region constitute a separate racial group which is in absolute majority there; it called for the creation of a special district to be directly subject to the central government in Rangoon. The memorandum also demanded that the district have a “district council” of its own which shall be vested with local autonomy.

The Rohingya Youth Association held a meeting in Rangoon on July 31, 1961, where the call was issued not to grant the status of “State” to Arakan because of the community tensions still existing between Muslims and Buddhists since the 1942 riots. A similar resolution was taken by the Rohingya Students Association, with the additional warning that if it is decided, despite all protest, to set up the “State”, this would require the partition of Arakan and the awarding of separate autonomy to the Muslims.

Muslim Members of Parliament from Maungdaw and Buthidaung likewise petitioned the government and the enquiry commission not to include their regions in the planned Arakan “State”. They had no objection to the creation of such a state, but only without the districts of Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and part of Rathedaung, where the Muslims were in the majority. These districts must be formed into a separate unit in order to ensure the existence of the Rohingya. Forcing the creation of a single state upon all of Arakan would be likely to lead to the renewed spilling of blood.

The problem of the Muslims of Akyab and the other regions of Arakan, where the Muslims were in the minority, were more complicated and their position led to tensions among the Rohinga organizations. There were those who deemed it pointless to object to U Nu’s plan of “Statehood” and therefore supported the granting of the status of “State” to the whole of Arakan, including the Muslim regions. They feared that separation of these regions would redound to the detriment of the Muslims in the rest of Arakan. They of course demanded guarantees and assurances for the protection of the Muslims; to this end they insisted that Muslims be co-opted to serve as members of the preparatory committee which would deal with the creation of the “State”.

At long last, it was on the first of May, 1961, in the provinces of Maungdaw, Buthidaung and the western portion of Rathedaung the government set up the Mayu Frontier Administration (MFA). It was not an autonomy, for the region was administered by Army officers; since it was not placed under the jurisdiction of Arakan, however, the new arrangement earned the agreement of the Rohingya leaders, especially as the new military administration succeeded in putting down the rebellion and in bringing order and security to the region.

At the beginning of 1962 the government prepared a draft law for the establishment of the “State” of Arakan and, in accordance with Muslim demand, excluded the Mayu District. The military revolution took place in March, 1962. The new government cancelled the plan to grant Arakan the status of a “State”, but the Mayu District remained subject to the special Administration that had been set up for it.

However, the Burmese successive military governments have singled out the Rohingya as a ‘threat to national security.’ The country’s military, the backbone of all governments since 1962, has pursued varied and evolving strategies to reduce, remove, replace, relocate and otherwise destroy the Rohingya. The state’s strategies range from framing the Rohingya as ‘British colonial era farm coolies’ from the present-day Bangladesh who came to British Burma only after the 1820s to painting the impoverished and oppressed Rohingya as potential Islamist’s intent on importing terrorism from the Middle East. From formulating and spreading the view of the Rohingya as aliens to enacting a national citizenship law to strip the Rohingya of their right of belonging – citizenship – to Burma. Even since 2012, they have lost not only their right to citizenship but also their right to self-identification and their right to enfranchise. Even their right to live is also at stake.

In spite of the above reality, ever since Burmese independence in 1948, the Rohingyas have been fighting for their very survival as a people. They have been struggling for their “Rights of self-determination”: which will guarantee their collective rights; the right to rule their homeland by themselves, the right to practice their religious teaching and culture freely, the right to teach, learn and promote their language freely, and the right to up-hold their identity without fear and live peacefully together with others. They have long been trying to identify themselves with the Union of Burma on the basis of equality and justice. They have long been searching a political and legal system which will allow them to rule their respective homelands by themselves, and at same time living peacefully together with others who practice different religions and cultures and speak different languages. In other words, they have long been searching a political system which can combine and balance between “self-rule” for different ethnic groups and “shared-rule” for all the peoples in the Union of Burma.

References:

1. Shwe Lu Maung, ‘The Rakhine State Violence’ Vol. 1, USA 2014, P.74, and also Rakhine Ah-man Hsaaung. Arakan Historical Research Association, August 1997.

2. History of Burma (1958-1962), Vol.3. University Press, Rangoon (1991), pp.167-68

3. Martin Smith, ‘Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity’, Dhaka (1991) p.81, and also Weekly Intelligence Summary, No.16, 19 April 1947, in ‘Law and Order, Arakan’ (IOR: M/4/1203)

4. Martin, P.82, in summary paper, Minute paper, B/C 1235/47, 12 August, 1947

5. Martin, p.82, Reuters,3 June 1947

6. Martin, P.82, E.g. ,British Intelligence Reported This demand was made at a meeting of 1, 000 supporters of the Muslim Jamiitut-Ulema in Maungdaw on 19 April, 1947, Weekly Intelligence Summary, No.19, 10 June 1947.

7. Shwe Lu Maung, pp.149-150