English translation of Mai Trazar’s political commentary on the military-political situation in western Myanmar. It outlines the junta’s shifting military strategy, the dynamics among ethnic armed groups, and the looming confrontations in Chin and Rakhine States.

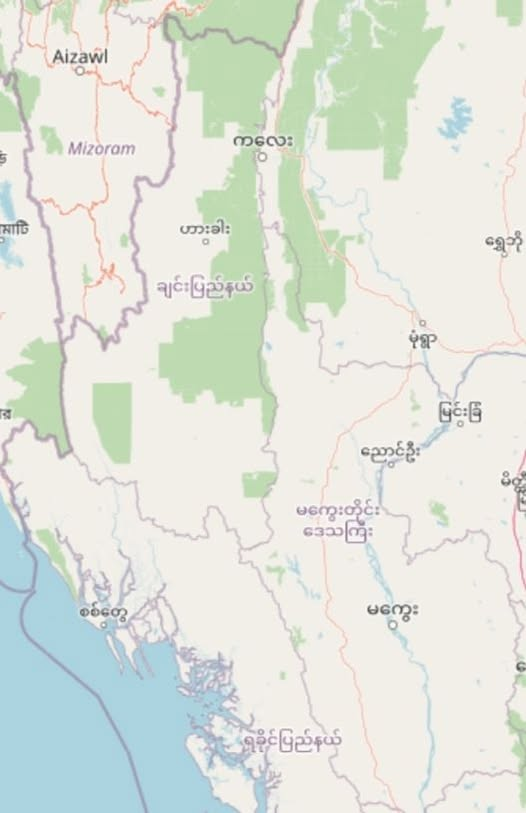

The western regions of Myanmar—Magway, Sagaing, Chin, and Rakhine—have become the military junta’s second front, with renewed military operations underway. The junta’s strategy avoids fighting all resistance groups simultaneously. Instead, it seeks ceasefires with some while crushing others, a tactic driven by limited manpower and resources.

With ceasefire agreements secured with TNLA and MNDAA, the junta now considers the eastern front secure. The RCSS and SSPP, two Shan armed groups, show no signs of preparing for conflict with the military. Both prioritize Shan self-rule and are wary of fragmenting Shan State further, especially with other groups like the Wa and those seeking separate states. Their leaders also have economic ties to the military, making collaboration more beneficial than confrontation.

In Karen State, the junta uses its proxy militias to destabilize resistance forces. This shift has made the western front—especially Chin and Rakhine—the new focus. The military’s activity in Sagaing aims to reclaim control over routes to India and clear the way for operations in Chin State. Similarly, Magway serves as a corridor into Chin. Once Chin is subdued, the junta is expected to launch a full-scale assault on Rakhine, followed by a third front, likely in the southern regions. The central plains may be the final target, especially after the elections, when the new government could label resistance groups as terrorists and justify military crackdowns.

In Chin State, the junta appears to prioritize the north over the south. No towns in the southern region have been designated for elections, indicating a strategic focus on the north. If the junta invades Rakhine via Chin, it’s likely that Chin resistance forces and the Arakan Army (AA) will coordinate to defend the region.

Currently, the routes into Chin—Laungshay-Saw, Pakokku-Kyaukhtu, and Gangaw-Kyaukhtu—are relatively secure. However, Gangaw-Yezwa and Gangaw-Hakha remain under watch. The military is advancing from Kalay, and Chin resistance has reportedly lost control of Webula. Falam and Tonzang are under threat, with reinforcements deployed in Tedim. The junta plans to retake Falam and Tonzang, possibly with ZRA’s help. The remaining three towns are being prepared for elections, even if only one vote is cast.

Once the north is secured, the junta will likely move into Rakhine. Meanwhile, the AA is fortifying Rakhine from outside, launching preemptive strikes from Chin South, Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady. The junta must first defeat local PDFs and CDFs before entering Rakhine.

The AA’s political goal, if not full independence, is at least confederation. The junta’s allies against AA include the ALP and four Rohingya armed groups, including ARSA, which has declared war on AA. ALP has grown stronger and is reportedly collaborating with the junta in Sittwe. The junta, seeing AA as a formidable enemy, is planning a decisive campaign to prevent its resurgence.

AA now faces a multi-pronged threat: accusations of human rights abuses from Fortify Rights, political pressure from Bangladesh over alleged drug links, and attacks from Rohingya armed groups. While China may exert pressure due to Rakhine’s strategic and economic value, it’s unlikely to match its influence in northern Shan.

Rohingya armed groups seek a designated territory in Maungdaw, which AA refuses. This has led to their alliance with the junta. However, if AA falls, the junta is unlikely to grant the Rohingya any real autonomy, and the Rohingya groups are aware of this. If AA is defeated, the junta’s next target may be the Rohingya armed groups themselves, and vice versa. ALP may then govern Rakhine as a BGF under the junta.

For AA, the only viable path is to achieve its political objectives independently. The junta, which has no intention of granting autonomy even to the Wa, will not offer concessions. Instead, it may manipulate parliamentary processes to marginalize AA. AA also refuses to align with the NUG, which is courting international support through human rights rhetoric and has promised to repeal the 1982 Citizenship Law. NUG has also appointed a Rohingya figure, U Aung Kyaw Moe, as Deputy Minister for Human Rights—moves that AA strongly opposes.

AA faces immense challenges. How it navigates these pressures and realizes its political vision remains to be seen. Likewise, the future of Rohingya armed groups and their aspirations will be closely watched.