From Sacred Symbol to Political Weapon — And How Myanmar Can Learn from Its Meaning

By Dr. Ko Ko Gyi Abdul Rahman Zafrudin

Editor’s Foreword

Across faiths and centuries, the simple act of throwing a stone has carried meanings far beyond violence. It has symbolized resistance, judgment, purification, and even love. This essay, reflects on how this enduring symbol—from the story of Cain and Abel to the streets of Gaza and the political battlegrounds of Myanmar—reveals much about the hand that throws it. His reflections merge the disciplines of medicine, history, and faith to illuminate one urgent question: when hatred is thrown into society, who really benefits?

I. Diagnosing the Political Stone

We Burmese often say, “Don’t just look at the target of the stone—look at who threw it.”

That proverb guides my understanding of politics. Trained as a physician by teachers such as Professor Dr Daw Myint Myit Aye, I learned to see every case holistically: the geography as anatomy, the history as physiology, the infection as propaganda, and the immune response as the people’s reaction.

My beloved, best teacher, Medical Professor Dr Daw Myint Myint Aye

So, when a stone of hatred is thrown—particularly the revival of Islamophobia by the junta—I ask: Who is behind the throw? Who ordered or paid the thrower? What do they wish to hide? And, most importantly, how can we prevent the next stone?

Just as a doctor traces the source of an infection, we must trace the source of fear. When anti-Muslim sentiment resurfaces, it is never spontaneous—it is induced, cultivated, and weaponized. The junta, facing internal collapse, diverts anger toward minorities to deflect attention from its crimes and failures. In medical terms, it inflames the national body to keep itself alive.

II. The Anatomy of Defense

During my civil-service days, I underwent basic military training at Paynggyi for five and a half months. There I learned Kyi Kwe/Myet Kwe—how to hide from sight, take cover, and deceive the enemy’s aim. Those lessons became metaphors for civic survival: sometimes we must conceal ourselves to survive; sometimes we must deflect and outthink those who attack.

Strategic defense, however, should not descend into vengeance. It means setting intelligent traps—legal, moral, and diplomatic—to restrain violence. One effective way to “kill two birds with one stone” is to use international mechanisms such as the ICC, ICJ, UNGA, UNSC, and R2P. Linking accountability for domestic crimes to global legal systems can stop both the Arakan Army–related and Rohingya genocidal abuses by raising their costs and exposure.

Even our cultural stories of stones carry meaning. Travelers to Shan State used to pick up a stone before the journey, saying “Mr Stone, follow us,” believing it would avert misfortune. And in Zaw One’s famous song, the lover calls himself a worthless street stone, yet vows to fill her muddy roads with paving stones—a humble metaphor for devotion and service.

Such stories remind us that the same object that wounds can also mend.

III. The Symbolism of Stones Across Faiths

As children we loved to skip flat stones across still water. In that playful gesture lies the oldest human instinct—to test strength, to measure reach, to create ripples.

Cain and Abel — The First Stone

In both Biblical and Islamic traditions, Cain struck his brother Abel with a stone. When guilt overwhelmed him, God sent a crow to teach him how to bury the body—and, symbolically, his sin—beneath the earth. From that moment, the stone became a witness to both crime and repentance.

Buddhist Parables

In Buddhist lore, Devadatta tried to kill the Buddha by rolling a huge rock down a hill. In another tale, a kind monkey rescued a Brahmin lost in the jungle, only to be struck with a stone when nearing the village—proof that gratitude and greed cannot share the same heart.

These stories show that the stone reflects the moral state of the thrower.

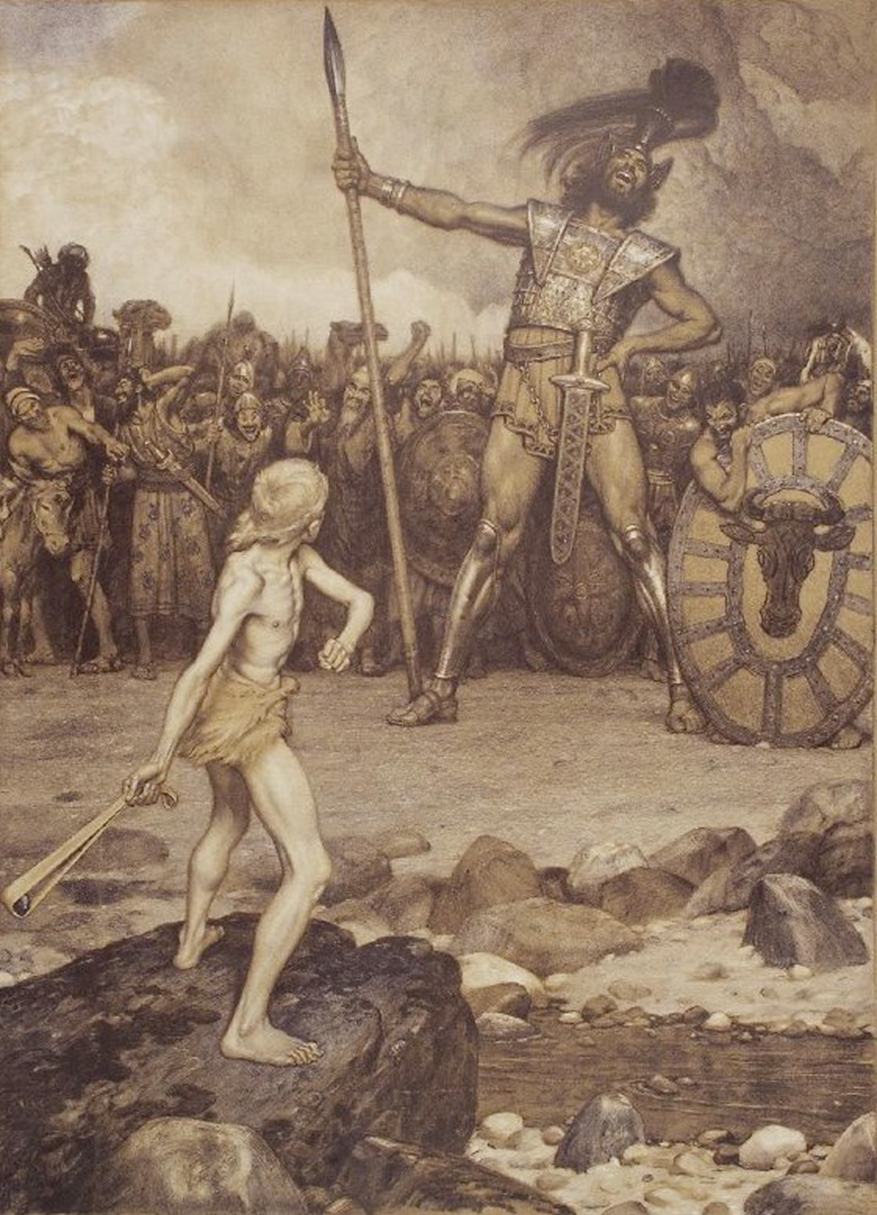

David and Goliath — The Courage of the Weak

The shepherd David faced the armored giant Goliath with only a sling and faith. His single stone toppled the oppressor and has ever since symbolized how the powerless can confront the powerful. As writer Jonathan Cook observed, stone-throwing has become an enduring symbol of resistance—the courage of the weak against overwhelming strength.

Wikipedia: Osmar Schindler (1869-1927) – http://www.schmidt-auktionen.de/

The Pilgrimage of Faith

During the Hajj, millions of Muslims perform the Rami al-Jamarat, “Stoning of the Devil.” Each pebble cast is a rejection of temptation and an affirmation of obedience to God. Violence is transformed into spiritual discipline—the redirection of anger into faith.

From Judgment to Mercy

In ancient Israel, stoning was the standard execution for grave offenses. Yet centuries later, Jesus of Nazareth transformed its meaning. When a woman accused of adultery was brought before him, he said, “Let him who is without sin cast the first stone.” (John 8:7) His words turned the act of punishment into an act of introspection.

Islamic jurisprudence, though later adopting stoning for certain hadd offenses through hadith, imposed near-impossible evidentiary standards—a reflection of the Prophet’s reluctance to punish without absolute proof.

Modern Resistance

Among Palestinians, stone-throwing has become an inherited form of protest—what scholars describe as “limited” or “restrained non-lethal” defiance. To the world it is often misunderstood; to them it remains a symbol of dignity and continuity, the shepherd’s tool repurposed for survival.

From Ecclesiastes—“a time to scatter stones, and a time to gather them”—we learn that the meaning of a stone depends on the season of the heart.

IV. From Sacred Stones to Modern Missiles

Even sacred traditions have turned to the act of throwing stones for moral expression. In ancient Palestine, both Muslims and Jews hurled stones at the Tomb of Absalom, condemning his rebellion against King David. The gesture survived as a moral ritual shared by all three Abrahamic faiths.

During the First Intifada, the stone returned as a political weapon. In 1989, Israeli paratrooper Binyamin Meisner was killed in Nablus when a cement block was dropped from a rooftop; in 2018, Ronen Lubarsky died similarly near Ramallah. These tragedies show how symbols of defiance can harden into cycles of vengeance.

The Qur’anic Sūrat al-Fīl recalls another story: when the Ethiopian Christian ruler Abraha al-Ashram marched on Mecca with elephants, God sent flocks of birds carrying stones of baked clay to repel them. The stone became a divine defense against arrogance.

Centuries later, Saddam Hussein echoed that imagery when naming one of his missiles al-Ḥijārah al-Ṣārūkh—“the stone that is a missile.” From hand-thrown pebbles to guided warheads, humanity’s violence has evolved in scale, not in spirit.

(Optional insert: educational video on projectile motion and gravity.)

Physics tells us every thrown stone obeys natural law—gravity pulling it downward, momentum propelling it forward—but morality governs why it was thrown. The trajectory of hatred, too, follows predictable laws: what goes up in rage must fall in ruin.

V. Healing the Hand That Throws

From Cain and Abel to the streets of Gaza, from Devadatta’s rock to the pilgrim’s pebbles at Mina, the story of the stone mirrors our moral struggle—between vengeance and mercy, faith and fear.

In Myanmar, when the junta revives Islamophobia to deflect blame, it merely repeats humanity’s oldest sin: turning fear into a weapon. The stone thrown at one community will eventually shatter the nation itself.

It is time we gather our stones—to build, not to destroy; to pave roads of justice, not graves of hatred. Let us be like the humble lover in Zaw One’s song, who uses stones to fill the potholes of life so others may walk safely.

Peace begins not when the stones are gone, but when the thrower’s heart is healed.

စေလိုရာစေ ဇော်ဝမ်း (2005) (စာသား စာတမ်းထိုး)