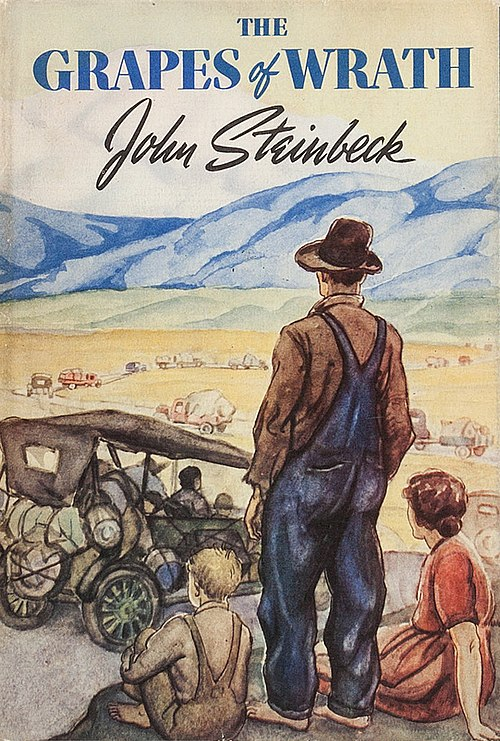

The Grapes of Wrath

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedi

The Grapes of Wrath is an American realist novel written by John Steinbeck and published in 1939.[2] The book won the National Book Award[3] and Pulitzer Prize[4] for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962.[5]

Set during the Great Depression, the novel focuses on the Joads, a poor family of tenant farmers driven from their Oklahoma home by drought, economic hardship, agricultural industry changes, and bank foreclosures forcing tenant farmers out of work. Due to their nearly hopeless situation, and in part because they are trapped in the Dust Bowl, the Joads set out for California on the “mother road“, along with thousands of other “Okies” seeking jobs, land, dignity, and a future.

The Grapes of Wrath is frequently read in American high school and college literature classes due to its historical context and enduring legacy.[6] A Hollywood film version, starring Henry Fonda and directed by John Ford, was released in 1940.

Religious interpretation

Many scholars have noted Steinbeck’s use of Christian imagery within The Grapes of Wrath. The largest implications lie with Tom Joad and Jim Casy, who are both interpreted as Christ-like figures at certain intervals within the novel. These two are often interpreted together, with Casy representing Jesus Christ in the early days of his ministry, up until his death, which is interpreted as representing the death of Christ. From there, Tom takes over, rising in Casy’s place as the Christ figure risen from the dead.

However, the religious imagery is not limited to these two characters. Scholars have regularly inspected other characters and plot points within the novel, including Ma Joad, Rose of Sharon, her stillborn child, and Uncle John. In an article first published in 2009, Ken Eckert even compared the migrants’ movement west as a reversed version of the slaves’ escape from Egypt in Exodus.[7] Many of these extreme interpretations are brought on by Steinbeck’s own documented beliefs, which Eckert himself refers to as “unorthodox”.[7]

To expand upon previous remarks in a journal, Leonard A. Slade lays out the chapters and how they represent each part of the slaves escaping from Egypt. Slade states “Chapters 1 through 10 correspond to bondage in Egypt (where the bank and land companies fulfill the role of Pharaoh), and the plagues (drought and erosion); chapters 11 through 18 to the Exodus and journey through the wilderness (during which the old people die off); and chapter 19 through 30 to the settlement in the Promised Land-California, whose inhabitants are hostile… formulate ethical codes (in the government camps)”.[8]

Another religious interpretation that Slade brings up in his writings is the title itself, stating “The title of the novel, of course refers to the line: He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored in Julia Ward Howe’s famous Battle Hymn of the Republic. Apparently, then the title suggests, moreover, ‘that story exists in Christian context, indicating that we should expect to find some Christian meaning’.”[8] These two interpretations by Slade and other scholars show how many religious aspects can be interpreted from the book. Along with Slade, other scholars find interpretations in the characters of Rose of Sharon and her stillborn child.

While writing the novel at his home, 16250 Greenwood Lane, in what is now Monte Sereno, California, Steinbeck had unusual difficulty devising a title. The Grapes of Wrath, suggested by his wife Carol Steinbeck,[13] was deemed more suitable than anything by the author. The title is a reference to lyrics from “The Battle Hymn of the Republic“, by Julia Ward Howe (emphasis added):

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

These lyrics refer, in turn, to the biblical passage Revelation 14:19–20, an apocalyptic appeal to divine justice and deliverance from oppression in the final judgment. This and other biblical passages had inspired a long tradition of imagery of Christ in the winepress, in various media. The passage reads:

And the angel thrust in his sickle into the earth, and gathered the vine of the earth, and cast it into the great winepress of the wrath of God. And the winepress was trodden without the city, and blood came out of the winepress, even unto the horse bridles, by the space of a thousand and six hundred furlongs.

The phrase also appears at the end of Chapter 25 in Steinbeck’s book, which describes the purposeful destruction of food to keep the price high:

[A]nd in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.

The image invoked by the title serves as a crucial symbol in the development of both the plot and the novel’s greater thematic concerns: from the terrible winepress of Dust Bowl oppression will come terrible wrath but also the deliverance of workers through their cooperation. This is suggested but not realized within the novel.