(Editorial Commentary – MMNN)

In the Rogasutta of the Cattukanipāta, the Buddha warned monks of four dangerous diseases that can quietly infect the Sangha. These were not physical illnesses, but spiritual and moral diseases — afflictions of the mind that could corrupt even those wearing the robe.

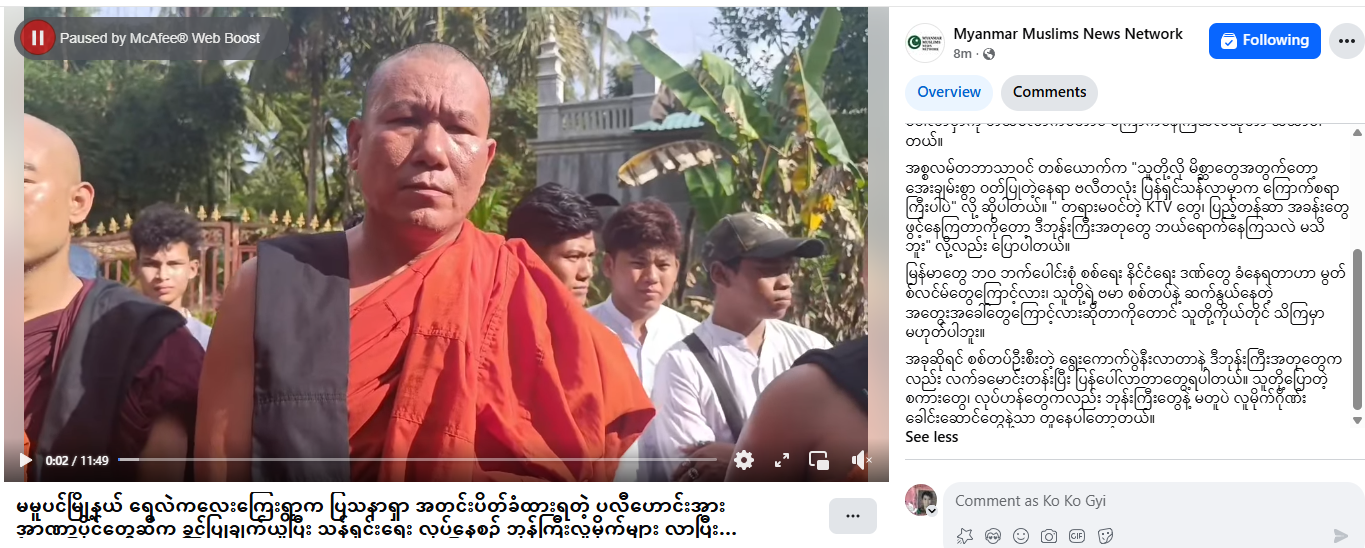

More than two thousand years later, these ancient warnings sound painfully relevant in modern Myanmar — especially among the powerful, politicized segments of the Sangha such as Thidagu Sayadaw, Wirathu, and other leaders of the Ma Ba Tha movement.

1. The Disease of Discontentment

The Buddha spoke first of monks who could not be satisfied with the four requisites — robes, alms food, lodgings, and medicine.

Today, this appears in the form of luxury monasteries, fleets of vehicles, foreign travels, and material wealth disguised as “religious donations.”

When monks grow restless and dissatisfied with simplicity, the robe itself becomes a symbol of status, not renunciation.

2. The Disease of Craving for Recognition

The second disease is the monk’s desire to be admired and respected — to be treated as a celebrity rather than a humble seeker of truth.

We see this in those who build political alliances, dominate television screens, or deliver nationalist speeches to cheering crowds.

When applause replaces meditation, and popularity becomes the measure of virtue, the Dhamma fades into vanity.

3. The Disease of Unrighteous Striving for Gain

The third disease is using improper or worldly methods to obtain offerings, fame, or influence.

In our time, some monks have turned religion into a political weapon — blessing weapons, endorsing violence, or dividing communities in the name of Buddhism.

When monks compete for followers, manipulate donors, or exploit fear for personal or institutional gain, they have fallen into the disease the Buddha warned against.

4. The Disease of Pretension for Fame

The fourth and most insidious disease is hypocrisy — pretending to be holy so that others may praise and follow.

This is seen when monks carefully stage their actions, words, and public appearances not for the sake of Dhamma, but for image-building.

It is a disease that thrives in the age of cameras and social media, where “influence” often replaces “insight.”

A Mirror from the Buddha Himself

The Rogasutta is not an attack on the Sangha; it is a mirror for it.

True monks live by contentment, humility, and endurance — not by publicity, profit, or politics.

When religion becomes nationalism, and monks become agents of hate rather than compassion, the robe loses its meaning.

A Message for Ma Ba Tha and Beyond

To the respected Thidagu Sayadaw, to Ashin Wirathu, and to all who have turned the noble robe into a banner of division:

The Buddha’s words still echo — “Monks should be content with little desire. They should endure heat and cold, pain and insult, with patience.”

This is not a political slogan.

It is a timeless cure for the moral epidemics that now threaten the spiritual health of Myanmar’s Sangha.

The disease is old, but so is the remedy: humility, compassion, and the abandonment of craving.