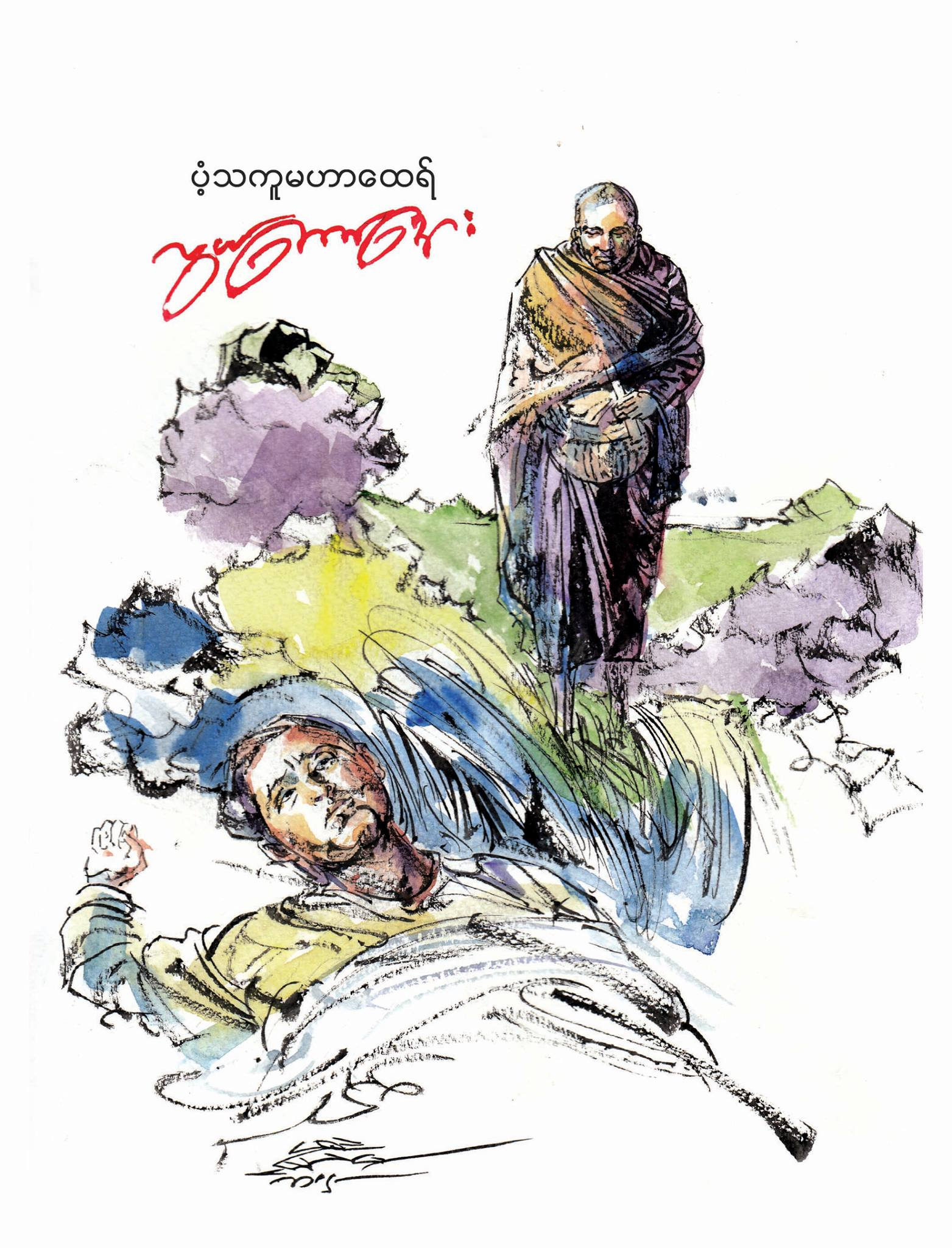

In the annals of Myanmar’s royal chronicles, few moments shine with such moral clarity as the confrontation between the venerable monk Pantagu Mahathera and the usurper king Narathu also known as Kala Kya Min during the Pagan era.

ဦးကုလားရာဇဝင်တွင် ပုဂံခေတ်က နောင်တော်ကို လုပ်ကြံကာ နန်းတက်သူ ကုလားကျမင်းအား ပံ့တကူမထေရ်ကြီးက

“ဟယ် – မင်းဆိုးမင်းညစ်၊

နင်ကား သံသရာဝယ် ခံရအံ့သော မကောင်းမှုကို မကြောက်၊

ဤစည်းစိမ်ကို ရလျှင် နင်၏ ကိုယ်ခန္ဓာသည် မအိုမသေပြီမှတ်သည်လော။

လောကတွင် နင့်ထက် ပျက်သော မင်းမရှိ၊

မင်းဆိုးမင်းညစ်အောက်တွင် ငါမနေပြီ”

ဟု လက်ညှိုးငေါက်ငေါက်ထိုးကာ သီဟိုဠ်ပြည်သို့ ထွက်သွားကြောင်း

As recorded in U Kala’s Maha Yazawin, this episode offers not only a glimpse into the political turbulence of the time, but also a timeless lesson in spiritual courage and ethical protest.

Narahthu ascended the throne after murdering his father King Alaungsithu and his elder brother Min Shin Saw. Narathu built the largest of all the Buddhist temples, the Dhammayangyi.[2] Nonetheless, his conduct greatly lowered the prestige of the dynasty, and he was deeply disfavored. The king was assassinated by the mercenaries sent by the chief of Pateikkaya in 1171. He is also remembered as “Kalagya Min” (ကုလားကျမင်း) (“The king fallen by the Kalars). (Ref: Wikipedia)

It is said that Narathu did not use water after using the toilet, and that the Pateikkaya queen did not let him come near her as a result. Narathu became angry, and killed a queen of his with his bare hands in a fit of range. The queen was a daughter of the chief of Pateikkaya, a tributary kingdom in the west in Bengal (near present-day Chin State).

The chief of Pateikkaya, angered by Narathu’s action, sent a group of eight assassins, disguised as Brahmin astrologers in 1171. The eight managed to gain an audience with the king while hiding their swords underneath their robes. They quickly slew the king. When the palace guards rushed in, they all committed suicide.

Following the assassination of the rightful heir to the Pagan throne, Narathu seized power under dubious circumstances. His rise was not merely a political maneuver—it was a betrayal of dynastic legitimacy and moral order. In response, Pantagu Mahathera, one of the most revered monks of the era, delivered a scathing rebuke:

“Hey — wicked and vile king, You fear not the karmic consequences that await in the cycle of rebirth. Do you truly believe that by gaining this wealth and splendor, your body shall never age or die? In this world, no ruler is more depraved than you. I shall no longer remain under the reign of such a corrupt king.”

With these words, the monk struck his staff in defiance and departed for the island of Sihala (Sri Lanka), a land long associated with Buddhist scholarship and refuge.

Yet the story does not end there.

Historical fragments suggest that on his journey, Pantagu Mahathera was compelled to stop at a pagoda, where he was forced to pay homage. Soon after, royal agents—likely under orders from the reigning monarch—intervened to forcibly summon him back. The monk’s attempted departure was not merely a spiritual exile; it was a political act. And in the eyes of the regime, no one, not even a revered monk, could defy the sovereign’s authority without consequence.

This episode raises enduring questions: Can moral authority stand above political power? Can spiritual protest reshape public conscience? And what does it mean when a monk must flee his homeland to preserve his principles?

Pantagu Mahathera’s defiance reminds us that the struggle for justice is not new. It is woven into the very fabric of Myanmar’s history—where monks, scholars, and ordinary citizens have long stood against tyranny, often at great personal cost.

As Myanmar Muslims continue to advocate for constitutional reform, inclusive democracy, and moral leadership, let us remember that the courage to speak truth to power is not a modern invention. It is our inheritance.