Translated from Ko Aung San Oo’s MMNN Burmese

Reports have surfaced that the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA), after significantly expanding its administrative, judicial, and public service systems across Rakhine State, has now drawn 202 Rakhine civil organizations to formally appeal to the United Nations and the international diplomatic community for recognition of Rakhine as an independent state.

This demand has raised a critical question for Myanmar’s political future — signaling that the Rakhine movement has evolved beyond mere political mobilization between secession and federalism, entering the phase of state-building.

1. What Does International Law Require to Be Recognized as a State?

Under international law, the 1933 Montevideo Convention outlines four essential criteria for a political entity to qualify as a state. When these are applied to the current situation of the ULA/AA, the findings appear as follows:

(1) A permanent population

The ULA/AA enjoys strong, consistent support from the Rakhine population and effectively governs them as its citizens. Hence, this condition appears fulfilled.

(2) A defined territory

The AA now controls most of Rakhine’s townships militarily and exercises tangible territorial authority. Although some territorial disputes persist, the fact that the AA holds substantial land outside central government control meets the basic foundation of statehood.

(3) An effective government

The ULA/AA has expanded its administrative and judicial systems and provides public services such as healthcare and education. It thus functions as a de facto government within its controlled areas.

(4) The capacity to enter into relations with other states

This remains the ULA/AA’s greatest challenge — and likely the primary reason behind its recent appeal to the UN and international actors. Without formal international recognition, the group cannot establish legitimate diplomatic relations with other sovereign states.

NUG and Ethnic Organizations’ Perspectives

The ULA/AA’s growing inclination toward separate nationhood presents a complex challenge for Myanmar’s broader pro-democracy forces, which are collectively striving to build a federal democratic union.

- The National Unity Government (NUG) seeks to establish a federal democracy recognizing ethnic self-determination but not secession. Therefore, NUG is unlikely to formally endorse any move toward independence. Should the AA consolidate control and secede, it could create major political complications regarding future federal borders and territorial integrity.

- Most other Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) also aim for maximum self-rule within a federal system, not full independence. While they may admire the AA’s administrative success, they are unlikely to support or emulate outright secession.

Conclusion

In practical terms, the ULA/AA is rapidly meeting several factual conditions of statehood under international law. Its growing administrative strength and strong public backing suggest that its dream of nationhood is no longer distant. The endorsement from hundreds of Rakhine civil organizations further reinforces its position internationally.

Myanmar now stands at a historic crossroads — whether it can remain a federal union, or whether ethnic regions like Rakhine, with effective governance and popular legitimacy, will eventually break away as independent entities.

Aung San Oo

(Myanmar Muslims News Network)

****************************************************************************

I hereby comment my point-of-view (POV) with likely scenarios about what ULA/AA’s push means inside Myanmar and for its neighbours (Bangladesh, India, China) and other Myanmar regions (Chin, Magway, Sagaing, Ayeyarwady). I’ve cited the most important recent reporting so you can follow up on any point.

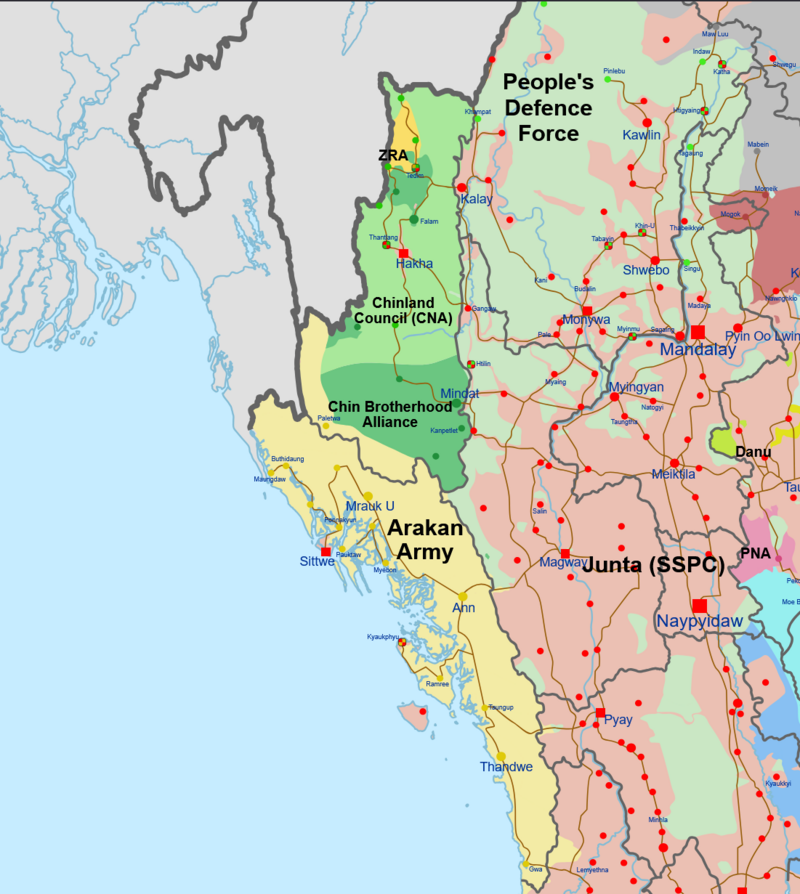

By Own work – Own work derivative of Myanmar civil war.svg by Ecrusized Et. al, which is derivative of Myanmar adm location map.svg by NordNordWest. Citing @ThomasVLinge, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=158416028

Short summary of the present moment (why this matters)

- The ULA/Arakan Army has expanded administrative control across large parts of Rakhine and — backed by hundreds of local civil groups — has publicly sought international engagement/recognition as a governing authority. That shifts the crisis from insurgency/negotiation to state-building on the ground, with real humanitarian and geopolitical consequences.

Four plausible scenarios (with my view of likelihood & consequences)

- Status quo / Continued de-facto autonomy (most likely near term)

- ULA/AA remains a strong de-facto authority in Rakhine without formal recognition. The group administers services, but lacks broad diplomatic recognition, so it must negotiate humanitarian access, trade, and border arrangements case-by-case.

- Consequences: chronic aid shortfalls, continued displacement toward Bangladesh, and contested border governance.

- Negotiated federal accommodation inside a future Myanmar framework (plausible medium term)

- If a credible federal political process (led by NUG or a post-junta settlement) re-emerges, the AA could accept strong autonomous status (extensive self-rule, security arrangements) in return for staying within a federal union.

- Consequences: could stabilize parts of west Myanmar but would require difficult compromises on borders, security forces, and resource control — and buy-in from other EAOs and the National Unity Government.

- Unilateral secession / de facto independence (lower probability near term, higher if international recognition grows)

- If the AA consolidates territorial control and outside states or international institutions begin to treat it as an interlocutor, Rakhine could effectively become independent in practice. Formal recognition remains hard — but not impossible — if humanitarian or strategic calculations push some neighbors to engage.

- Consequences: fragmentation of Myanmar, violent clashes over borders and resources, long-term refugee flows, and regional instability.

- Junta reconquest or external brokered rollback (uncertain but possible)

- The military could attempt to retake Rakhine (with Chinese or other tacit support), or China/ASEAN mediators could push ceasefires and an interim arrangement. The outcome depends on military balance and external patrons.

Implications for neighbours

Bangladesh — immediate humanitarian & security pressure (high impact, high likelihood)

- Rakhine instability will keep pushing Rohingya and other displaced people into Bangladesh, worsening an already dire refugee burden. Bangladesh will face security challenges if armed groups use camps or border zones for operations or recruitment. Dhaka will have to balance humanitarian needs with strict border controls and political pressure.

- Bangladesh options: engage the AA as a pragmatic local interlocutor for repatriation/aid; pressure internationally for protections; or strengthen border containment — each option has diplomatic costs.

India — infrastructure and northeast security concerns (strategic, medium-high impact)

- Western Myanmar (Rakhine) hosts infrastructure projects of interest to India (ports, the Kaladan corridor). Persistent instability threatens those projects and could push refugee and militant flows toward India’s northeast, complicating New Delhi’s security calculations. India will therefore favor stability — likely preferring negotiated autonomy rather than outright fragmentation — but could pursue local ties to protect its projects.

China — pivotal regional arbiter (very high impact)

- Beijing prefers a stable land route and a government in Naypyitaw that safeguards its investments, but it also cultivates relationships with ethnic armed groups as leverage. China may act as a broker (ceasefires, mediation) or quietly support whichever side preserves its strategic interests (infrastructure, ports, corridors). China’s posture could determine whether the junta can attempt reconquest or whether a durable accommodation is possible.

Implications for other Myanmar regions and ethnic armed groups

- Chin State (bordering Rakhine): spillover of conflict, new displacement, and pressure on limited local services. Chin groups may be pressured to pick sides or demand similar autonomy.

- Sagaing, Magway, Ayeyarwady (central-west regions where fighting has spread): the trend of armed groups expanding beyond traditional territories (AA activity into Ayeyarwady and junta counter-offensives in Magway/Sagaing) risks a wider national fracturing: multiple semi-autonomous zones with different authorities. This would complicate any federal bargain and raise humanitarian needs.

Humanitarian and legal ripple effects

- Aid access: If the AA is treated as the on-the-ground authority, humanitarian agencies will face hard choices about negotiating access, which some states may view as implicit recognition. That is likely the AA’s motive in seeking international engagement.

- Refugee law / repatriation: Bangladesh won’t repatriate Rohingya unless safety and legal guarantees exist on the Myanmar side. The AA’s control complicates repatriation unless Dhaka negotiates with AA or an international guarantor.

Likely short-term outcomes (next 6–18 months)

- Continued de-facto AA governance in much of Rakhine, intermittent clashes, larger humanitarian needs in the state and Bangladesh.

- Regional hedging: Bangladesh, India, and China will quietly calibrate local contacts with AA while publicly calling for stability and humanitarian access. China’s role as mediator or backer will be decisive.

- Political bargaining — either a frozen status quo, a local power-sharing deal, or steps toward more formal autonomy inside a future federal structure — will shape whether fragmentation becomes permanent.

Recommendations / policy options (for international community or regional actors)

- Prioritize humanitarian access and protections (UN/NGOs should push for neutral corridors and engagement with whoever controls territory so civilians are not used as pawns). Evidence shows urgent food insecurity and malnutrition in Rakhine; aid must not be politicized.

- Use regional mediation (China/ASEAN) to secure ceasefires and a roadmap for local governance — not recognition per se, but shared mechanisms for repatriation, aid, and policing. China is the practical broker with leverage over the junta and local actors.

- Bangladesh should pursue a combined humanitarian-diplomatic track that engages international donors and explores a conditional returns framework with credible guarantees involving neutral monitors.

- India should protect vital projects and the northeast by supporting local stability mechanisms and by strengthening diplomacy with both Naypyitaw and regional actors.

Final POV

The ULA/AA’s bid for recognition is not merely a rhetorical escalation — it marks a material shift toward state-building. In isolation, recognition is unlikely; in practice, the group already meets many de-facto conditions of authority. The main question is whether regional powers and international institutions will treat the AA as a partner for pragmatic governance (aid, border management, infrastructure) — which would consolidate a new reality — or whether they will uphold Myanmar’s territorial integrity and push for reintegration. Either choice has cost: either long-term fragmentation and new borders in mainland Southeast Asia, or renewed war as the junta or others try to reassert control. The path chosen by China, Bangladesh, and India — and the availability of a functioning federal political alternative inside Myanmar — will determine which future arrives.