China’s Influence on Wa, EROs, and Myanmar’s Revolution

A three-part analysis for MMNN

Part 1: Wa and Self-Determination

Intro:

This is the first part of a series exploring China’s influence over Myanmar’s ethnic armed organizations (EAOs). Here we look at the Wa, a force often dismissed as a “Chinese colony,” but whose identity and struggle for self-determination deserve to be understood on their own terms.

The Wa are not a confederacy, nor are they merely a colony of China or just another rank of Burmese rebels. Labeling them in this way is both offensive and misleading. The Wa people have their own identity, language, and aspirations for self-determination. To say they are simply an extension of Chinese power strips them of their agency. China does exercise influence, particularly through arms supplies, cross-border trade, and political leverage. Yet the Wa themselves maintain their own governance structures, their own administration, and a clear sense of being Wa above all else.

When outsiders lazily reduce them to proxies, it obscures the more complex reality: that they are simultaneously wary of China, engaged with Myanmar, and determined to preserve their autonomy. Their legitimacy in the ethnic political landscape comes not from Beijing, but from their own ability to organize and sustain themselves. This is why dismissing the Wa as mere puppets of China is not only unfair but dangerously simplistic.

Closing note:

The Wa story reminds us that labeling groups through external lenses hides their real aspirations. China’s shadow looms large, but the Wa’s determination to define their own future is equally strong.

Part 2: China’s Maneuvers Among EROs

Intro:

This second part of the series examines how China positions itself among Myanmar’s ethnic revolutionary organizations (EROs). Far from being a neutral neighbor, Beijing carefully calibrates its involvement to maintain leverage, even at the expense of Myanmar’s democratic struggle.

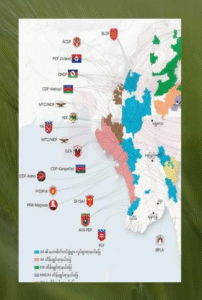

China’s role in Myanmar’s revolution is often disguised as quiet diplomacy, but in reality it is active manipulation. Beijing keeps close ties with multiple EROs — not to help their struggle, but to maintain bargaining chips against both the junta and the opposition. It supplies weapons selectively, brokers ceasefires when convenient, and pressures groups that lean too far toward Western support.

By doing so, China keeps everyone dependent and divided. For EROs, this creates a paradox: they may rely on Chinese channels for arms or logistics, yet they also know Beijing’s priority is not their freedom but its own border stability and geopolitical leverage. The revolution gains energy from grassroots movements, not from Beijing’s maneuvers. Yet China’s shadow is always present — reminding everyone that the dragon never lets go of what it sees as its periphery.

Closing note:

China’s selective support for EROs is not about justice, but about control. Understanding these maneuvers is key to grasping why Myanmar’s revolution cannot rely on outside powers.

Part 3: China’s Double Game in Myanmar

Intro:

The final article in this series turns directly to Beijing’s double game. From the 2020 elections to the present, China’s miscalculations have deepened Myanmar’s turmoil — caught between fear of the West and fear of losing influence on the ground.

In Myanmar’s turbulent landscape, China—often referred to as Pauk Phaw—is playing a dangerous double game. What began as calculated maneuvers to secure influence after the 2020 elections has now spiraled into confusion, miscalculations, and mounting sacrifices.

Before the 2020 election, China encouraged the formation of a proxy party. Yet, the NLD sidelined it. When the NLD won and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi rushed to meet Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, it seemed Beijing was hedging its bets. Not long after, the military coup overturned the political table.

But the coup did not deliver the stability China wanted. The people rose in massive resistance. Beijing’s attempt to manipulate events through the so-called “Tiger Operation” and by encouraging the Northern Three alliances (KIO, MNDAA, TNLA) to launch offensives backfired. The weapons supplied by Wa—under Chinese blessing—fueled not only conflict but also the flood of narcotics across the region.

Ironically, the very offensive Beijing sponsored ended up energizing the revolution and strengthening the NUG’s position. When this displeased China, it tried to distance itself from the NUG and worked to undermine it. The Northern Three and communist-aligned groups began clashing with the NUG, and even within the NUG, divisions between communist and democratic factions emerged.

China soon realized its actions were producing more harm than good. It tried to rein in the Northern Three, only to be rebuffed. As long as the groups held weapons, they were unwilling to fully submit to Pauk Phaw’s dictates. Beijing responded by attempting to cut off their lifeline: the Wa arms route.

Arms and narcotics travel together, and when the supply chain is disrupted, the ripple effects are immense. Recently, a Naga news outlet accused the CNF of trafficking drugs. Given China’s long and murky ties with Naga groups, this raises suspicions. Is Beijing targeting CNF because of its closeness to Western allies? Or is it signaling that narcotics routes have shifted toward Naga territory?

Either way, China is tightening its grip. Reports suggest arms supplies to the Arakan Army have been curtailed, while narcotics flows face new disruptions. Whether Yangon becomes an alternative route remains unclear.

What is undeniable is Beijing’s profound fear of the West. Any organization perceived as leaning toward Western influence is infiltrated, weakened, or attacked through multiple methods. The fear of a “Western foothold” in Myanmar drives Beijing’s paranoia.

At the same time, Russia’s rise gives Beijing some protection from US sanctions. Washington cannot tax China heavily without provoking Moscow. Instead, India—“Pa Bu”—absorbs the pressure. And because India shares a border with Kachin, it too will have to devise its own responses.

The cost of China’s schemes has been paid in blood. Many lives have already been sacrificed, and more will be lost as Beijing presses forward. Yet, China does not fully trust Min Aung Hlaing either.

One certainty looms: in the coming months, Beijing will intensify pressure—politically, militarily, and economically—on KIO, CNF, NUG, KNDF, and KNU. China’s “Pauk Phaw” narrative is no longer about friendship. It is about control, fear, and manipulation. Behind its maneuvers lies a deeper anxiety: that one day, the mythical Garuda may rise—and slay the dragon.

Closing note:

What emerges is a portrait of a superpower obsessed with control but plagued by insecurity. China may manipulate, divide, and pressure, yet beneath the surface lies a deeper fear: that one day the Garuda may rise to slay the dragon.