Once, I published a translated a short story in English..a young Maung Paw Tun Aung once rejected a Second Prize medal in fourth standard by throwing it into the Kaladan River while resolving to aim for First Prize — appears to be part of oral memory or a personal translation I published in Burma Digest.“According to stories recorded in Burma Digest and community memory, the young Maung Paw Tun Aung once discarded a second-place academic medal, awarded by the British District Edition Officer into the Kaladan River, declaring his ambition to earn first prize to his younger brother Tun Kyaw Aung. While not documented in mainstream biographies, this anecdote reflects his youthful temperament and high self-expectation.” “Young brother, in any exam you have to aim for the first position” (Note of DARZKKG)

For readers in Myanmar, regardless of nationality, Dalrymple’s account of imperial Britain’s rule over its Burmese colony is detailed as well as comprehensive. As expected, he deals at length with anti-Indian sentiments as well as early ties between Indian and Burmese nationalist movements.

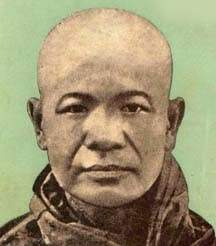

It is often overlooked that the monk U Ottama (Rakhine Monk), an early leader of the independence movement, had as a young man joined the Indian National Congress and later brought Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent campaigns to Burma. According to Dalrymple: “So closely was he identified with the Mahatma that upon him being arrested by the British authorities, eight thousand people gathered at the Shwedagon Pagoda in protest, christening him ‘Mahatma Ottama’.”

From Wikipedia:

Sayadaw U Ottama (Burmese: ဆရာတော် ဦးဥတ္တမ [sʰəjàdɔ̀ ʔú ʔoʊʔdəma̰]; Pali: 𑀉𑀢𑁆𑀢𑀫, Uttama; 28 December 1879 – 9 September 1939) was a Theravada Buddhist monk, author, and a leader of the Burmese independence movement during British colonial rule. The ethnic Rakhine (Arakanese) monk was imprisoned several times by the British colonial government for his anti-colonialist political activities.[1]

Biography

Early life

He was born Paw Tun Aung, son of U Mra and Daw Aung Kwa Pyu, in Rupa, Sittwe District,[2] in western Burma on 28 December 1879. Paw Tun Aung assumed the religious name Ottama when he entered the Buddhist monkhood.

Education

Ashin Ottama studied in Calcutta for three years. He then travelled around India, and to France and Egypt.

In January 1907, he went to Japan, where he taught Pali and Sanskrit at the Academy of Buddhist Science in Tokyo. He then travelled to Korea, Manchuria, Port Arthur, China, Annam, Cambodia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India. In Saigon, he met with an exiled former Burmese prince, Myin Kun (who led a rebellion along with Prince Myin Khondaing in 1866 and assassinated the heir to the Burmese Crown, Crown Prince Kanaung).

Anti-colonial and political activities

Upon his return to British Burma, U Ottama started his political activities, toured the country, lecturing for the Young Men’s Buddhist Association and giving anti-colonial speeches. In 1921, he was arrested for his infamous “Craddock, Get Out!” speech against the Craddock Scheme by Sir Reginald Craddock, then Governor of British Burma. Repeatedly imprisoned on charges of sedition, he carried on. Ottama was one of the first monks to enter the political arena and the first person in British Burma to be imprisoned as a result of making a political speech, followed by a long line of nationalists such as Aung San and U Nu.

Inspired by Gandhian principles, U Ottama advocated nonviolent resistance, promoting peaceful protests, boycotts of British goods, and a revival of indigenous values and self-reliance. He framed his opposition to colonial rule through Buddhist ethics, creating a compelling message that strongly resonated with the Burmese people.[3] According to academics; between 1921 and 1927, U Ottama spent more time in prison than outside.

While Ashin Ottama did not hold any post in any organization, he encouraged and participated in many peaceful demonstrations and strikes against British rule. An admirer of Mahatma Gandhi, he did not advocate the use of violence.[4]

He represented the Indian National Congress at the funeral of Dr. Sun Yat-Sen in June 1929. The only time he held a post was as leader of the All India Hindu Mahasabhas in 1935.

Demise

U Ottama died in Rangoon Hospital on 9 September 1939.

Legacy

U Ottama’s legacy remains significant in modern Myanmar. His contributions are commemorated through annual events in Sittwe and Yangon. His former monastery, Shwe Zedi in Sittwe remains as a historically relevant associated with political and social activism.

Annually, his death-recorded on 9 September 1939 is commemorated by various groups in Myanmar and abroad. These commemorations are often referred to as “U Ottama Day” is served to honor his memory and to remind contemporary generations of the long struggle against colonial oppression. His anniversary is widely observed across Arakan State including Kyaukphyu, Taungup and other townships. In abroad, it was marked on a smaller scale in Thailand, Malaysia, Bangladesh and Japan.

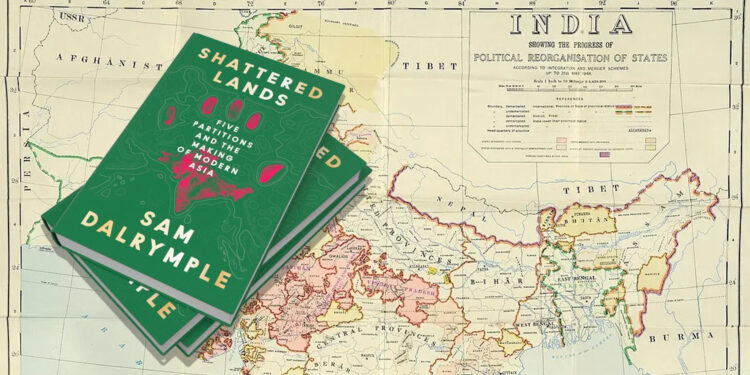

Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia

by Sam Dalrymple

William Collins, London, 2025

520 pp. £25

This book is bound to become a classic. Sam Dalrymple, a Scottish historian, filmmaker and peace activist who grew up in India and studied Persian and Sanskrit at Oxford University in the United Kingdom, has in this powerful, graphically written work described the emergence of no fewer than 12 independent nations from what was once Britain’s Indian Empire — and how its eventual collapse has shaped today’s Asia with all its contradictions and internecine conflicts.

The extremely painful and bloody 1947 birth of Muslim Pakistan and predominantly, but not exclusively, Hindu India may be what most students of Asian history think of in the context of the breakup of Britain’s possessions in South Asia. But that is actually “the third partition” on Dalrymple’s list. The first occurred in 1937 when Burma, a province of British India since 1886, was turned into a separate colony.

The second partition began in the same year, 1937, and led to the British dependencies on the Arabian Peninsula becoming separate entities and, eventually, independent nations. Until oil and gas was discovered in the desert, those states — among them the now immensely rich Dubai in the United Arab Emirates — were poor and underdeveloped. Only Yemen, which now consists of the once independent, northern monarchy of Yemen, the former British colony of Aden and an adjoining protectorate, remains a conflict-ridden basket case.

The creation of India and Pakistan in 1947 was followed by the abolishment of hundreds of princely states, which had been semi-autonomous territories under British suzerainty. Dalrymple lists that as the fourth partition because the rulers of those states had to decide whether to join Pakistan or India. The fifth and final partition took place in 1971, when the eastern part of Pakistan broke away and became Bangladesh. With the rise of Bengali nationalism, religion alone could not keep the two parts of Pakistan together.

In addition, the Himalayan kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan, which were protectorates of British India, have also become fully independent nations, but through gradual processes. And the eventual outcome of all those developments is the formation of the current 12 countries of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Oman and Yemen. Detailed historical as well as contemporary maps show the locations and boundaries of those territories.

The 1947 partition of India and the subsequent integration of the princely states led to one of the bloodiest conflicts in modern Asian history. The rulers of those states had to decide which country they wanted to belong to, India or Pakistan, and that happened largely along religious lines. But the Muslim Nizam of Hyderabad, a state with a Hindu majority in southern India, declared his intention to become independent while the Hindu maharaja of Jammu of Kashmir, who ruled over a majority Muslim population, entertained similar ideas.

In the end, a military operation, which was euphemistically called a “police action”, resulted in the accession of Hyderabad to India. In Jammu and Kashmir, the maharaja gave up his quest for independence after Pakistan-supported militias tried to invade the state. He then decided to join India — and that has led to several wars between India and Pakistan. India now administers the southern and southeastern parts of the erstwhile princely state, including the Kashmir Valley, Jammu, and Ladakh, while the Pakistanis control the northern and western parts, known to them as Azad Kashmir (literally Free Kashmir) and Gilgit-Baltistan. The conflict has been exacerbated by Pakistan’s decision in 1963 to cede approximately 5,300 square km of territory to its ally China, a move which, understandably, has been condemned by India.

It is estimated that between 12 and 20 million people were displaced in the late 1940s. Hindus and Sikhs fled to India and Muslims to Pakistan, creating a population transfer unseen anywhere else in the world at the time. As many as 2 million people may have died in the ensuing violence, while India as well as Pakistan have since then built up some of the world’s most powerful armies. Both countries also possess nuclear weapons.

Dalrymple outlines the origin and development of the conflict between India and Pakistan brilliantly and with great objectivity. At the same time, he states that “it is perhaps inevitable that I am not detached from the conflicts that appear within the pages of this book. My own grandfather witnessed the Great Partition [1947] and in forty years of my family living in Delhi he always refused to visit us on account of what he saw in 1947. Many of the friends I grew up with in Delhi, or friends I later made living in Lahore, have similar family stories.” He adds that “no truth or reconciliation mission has ever tried to address any of the deep-seated traumas of the fifth of the world’s population whose lives are daily informed by these great tragedies.” Such personal observations make the book all the more readable and compelling. It is not just an academic study compiled at some faraway university, or a heated account written by promoters of only one side of the story.

Among the Arab territories which were tied to Britain’s Indian Empire, Dalrymple highlights some different developments. Dubai consisted at the start of the 20th century of “a collection of mud forts and a few thousand mostly nomadic residents.” But “in the coming years, two new countries would be forged from the former princely states of the Indian Empire — the United Arab Emirates and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. One through federation and the other through revolution.”

Dubai, one of the wealthiest of the seven states that formed the independent United Arab Emirates in 1971, is now a playground for the rich and famous while Yemen has become torn apart by devastating wars and is partly ruled by Islamic extremists. As Dalrymple writes, “The change that overcame the Arabian Peninsula in these years is not well known, but it should be, for it laid the foundations of the Gulf War, the Yemeni civil war and the rise of Dubai.” To the best of my knowledge, Dalrymple is the first writer to analyze these developments against the backdrop of Britain’s failed colonial policies, including the chaotic breakup of its Indian Empire.

For readers in Myanmar, regardless of nationality, Dalrymple’s account of imperial Britain’s rule over its Burmese colony is detailed as well as comprehensive. As expected, he deals at length with anti-Indian sentiments as well as early ties between Indian and Burmese nationalist movements. It is often overlooked that the monk U Ottama, an early leader of the independence movement, had as a young man joined the Indian National Congress and later brought Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent campaigns to Burma. According to Dalrymple: “So closely was he identified with the Mahatma that upon him being arrested by the British authorities, eight thousand people gathered at the Shwedagon Pagoda in protest, christening him ‘Mahatma Ottama’.”

However, anger against Chettiar moneylenders from India — and the fact that Indian soldiers in the British army had been instrumental in putting down the 1930-1932 rebellion led by the physician and monk Saya San — brought about anti-Indian riots in Rangoon (now Yangon) and elsewhere. During and after World War II, and, especially, in the aftermath of the military takeover in 1962, hundreds of thousands of Indo-Burmese left for India. Rangoon, where Indo-Burmese had made up the majority before the war, became a predominantly Burmese city.

Dalrymple does not address the issue, but one can only speculate what might have happened if Burma had remained in the Commonwealth when it became independent in 1948. The problem was that independence from Britain in those days meant dominion status where the countries became fully self-governing while the British monarch remained head of state represented by a governor-general. India, Pakistan and Ceylon accepted that, but it was politically impossible in Burma, where leftist forces, including a powerful communist party, yielded significant influence over domestic policies. So Burma chose to become a republic and not a member of the Commonwealth.

That changed on January 26, 1950, when India became a republic — and remained in the Commonwealth. Pakistan followed suit in 1956, and, as late as in 1972, Ceylon also became a republic within the Commonwealth and changed its name to Sri Lanka. Today, only 15 of its 56 members — nearly all of them former British colonies — are what used to be called dominions and now Commonwealth realms. The rest are republics, and that was made possible only because India as a strong and powerful country was allowed to break the old rules.

If Burma had accepted dominion status in 1948, and, after a few years of independence, become a republic, history might have been different. The stated ideals of the Commonwealth might have been less clear and compelling in its early years, but the bloc has become committed to the promotion of representative democracy and the upholding of human rights, and is known to have put pressure on and even suspended countries where military takeovers have taken place. In any event, the haphazard way in which Britain left Burma and the wars between its different nationalities, which broke out almost immediately after independence, are the bitter legacies of colonial rule. And for the overall picture of such policy failures in the entire region, there is no better source than Dalrymple’s book.

by

by