The Pyu city-states were among the earliest known urban cultures in Southeast Asia, flourishing in present-day Upper Myanmar from around the 2nd century BCE to the mid-11th century CE. They were established by the Pyu people, Tibeto-Burman speakers who migrated southward and became the earliest documented inhabitants of the region. This thousand-year period—often referred to as the Pyu millennium—bridged the late Bronze Age with the dawn of classical Myanmar, eventually giving rise to the Pagan Kingdom in the 9th century.

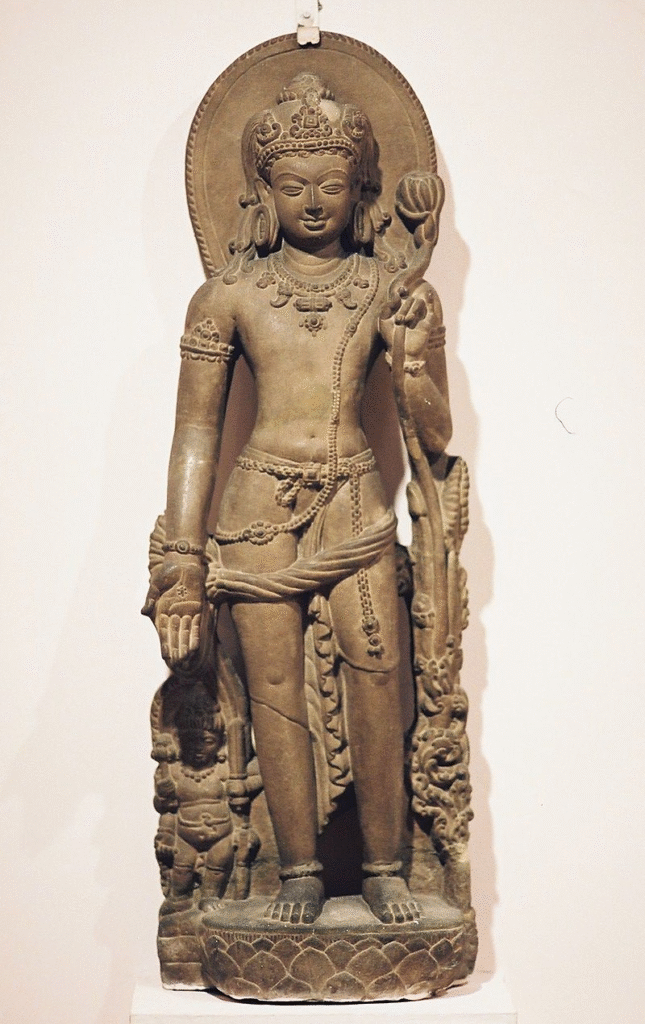

Avalokiteśvara holding a lotus flower. Bihar, 9th century, CE. The Pyu followed a mix of religious traditions.

Source: Wikipedia By Hyougushi – https://www.flickr.com/photos/hyougushi/27767674/in/set-1101828/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5259522

The Pyu established sophisticated urban centers across fertile, irrigated regions of Upper Burma, especially in the Mu River valley, the Kyaukse plains, and the Minbu region near the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Chindwin Rivers. Archaeological excavations have revealed five major walled cities: Beikthano, Maingmaw, Binnaka, Halin, and Sri Ksetra, along with numerous smaller settlements spread throughout the Irrawaddy basin. Among these, Halin, founded in the 1st century CE, was initially the most significant, until it was surpassed by Sri Ksetra around the 7th or 8th century. Sri Ksetra, located near modern-day Pyay, was the largest, most enduring, and most influential of the Pyu centers—twice the size of Halin. Today, Halin, Beikthano, and Sri Ksetra are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, with other Pyu sites considered for future extension nominations.

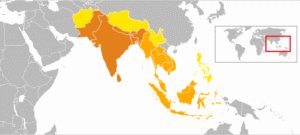

The Pyu civilization sat astride an overland trade route connecting China and India, which brought not only goods but also powerful cultural influences. Through Indian contact, the Pyu adopted Buddhism, Brahmic scripts, and Indian-inspired political and architectural models. These imports would leave a lasting imprint on Myanmar’s culture. The Pyu script, derived from the Brahmi script, may have served as the prototype for the Burmese script, while the Pyu calendar, based on the Buddhist calendar, evolved into the Burmese calendar still in use today. Importantly, the Pyu were the earliest people in Southeast Asia to develop tonal markers to adapt Brahmic scripts for tonal languages.

This millennium-long civilization came to an abrupt end in the 9th century, when it was devastated by repeated invasions from the Nanzhao Kingdom, based in present-day Yunnan. As early as 754 or 760 CE, Nanzhao forces began raiding Upper Burma, and by 763, their king Ko-lo-feng had conquered large swathes of the Irrawaddy Valley. The raids intensified between 800 and 809 CE, culminating in a devastating campaign in 832 CE, when the Chinese records note that 3,000 Pyu prisoners were taken from Halin. Some scholars also believe a Pyu state was targeted again in 835 CE, though this identification remains debated.

In the wake of the invasions, a new group—the Burmans (Mranma)—established a military garrison at Bagan (Pagan). By the late 10th century, they had assumed control of former Pyu territories and traditions. Although Pyu settlements and the Pyu language persisted in Upper Burma for another three centuries, the people were gradually absorbed and assimilated into the rising Pagan Empire. By the 13th century, the Pyu had vanished as a distinct ethnic group, and their language disappeared from use.

Nevertheless, the legacy of the Pyu endured. Pagan’s Burman rulers claimed descent from the ancient kings of Sri Ksetra and even Tagaung, with some royal genealogies stretching mythically back to 850 BCE—claims modern scholars largely dismiss. Yet, this myth-making illustrates how deeply the Pyu civilization influenced Burmese identity, culture, religion, and writing. The Pyu’s role in shaping the foundations of Myanmar’s classical age remains profound and irreplaceable.