By Dr. Ko Ko Gyi Abdul Rahman Zafrudin with the MMNN Editorial team

History, as we know, is often written by the victors—but at times, conveniently edited by the insecure.

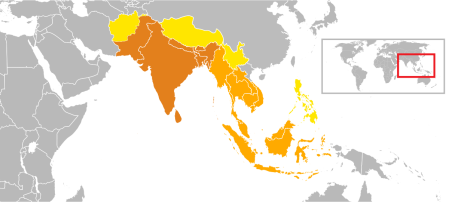

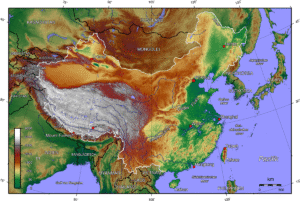

Among the fascinating, yet forgotten, tales of Southeast Asia is the story of the Talines—a people once recognized as a mixed race, descendants of Mon-Khmer bloodlines interwoven with Talagu, the legendary seafarers from the eastern coast of India. These early communities had likely sailed through the Bay of Bengal, settled along the coastlines of what is now Myanmar, and merged over generations with the Mon and Khmer populations descending from southern China.

The Talines were not a myth. They were a distinct identity, and their mark on regional history was profound. As recorded in early Malaccan chronicles, during the height of Melaka’s trading glory, up to 30 ships a day from Pegu (Lower Burma) arrived in its port. These traders, known locally as “Pegu Thars,” were among the key founders of the Melaka Sultanate—alongside Malays, Indonesians, Arabs, Indians, and Chinese Muslims.

In fact, one of Malaysia’s six remaining Orang Asli (aboriginal) groups still speaks a Mon-Khmer language, a living linguistic relic of this ancient interwoven heritage. But the name Taline, once proudly carried, gradually faded into obscurity.

Why?

The Erasure of “Taline”

During the era of General Ne Win in Burma (1962–1988), a strange but telling revisionist trend took place. The Mon-Taline community, possibly in a bid to appear more “pure” and acceptable in the face of rising ethnic nationalism, wiped out the Taline identity from public memory, erasing the Indian-origin ancestry embedded within it. The term “Mon” was retained; “Taline” was buried.

This sanitization of ethnic roots is not uncommon in post-colonial Asia. But it leaves behind cultural amnesia and a fragmented understanding of who we really are. It is tragic that what was once a vibrant mixed heritage had to be hidden under the weight of political insecurity.

Tunku’s Mon-Burmese Roots

Now here comes an even more surprising twist. When I was working with PERKIM, Malaysia’s national Muslim welfare organization, and RISEAP, the regional Islamic council for Southeast Asia and the Pacific—both chaired by Malaysia’s first Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman—we often discussed heritage and identity.

It was widely believed that Tunku’s mother was a Thai lady. But deeper historical digging and informal conversations among PERKIM staff revealed a different story. According to Tunku Aziz, the late Senator and Tunku’s own nephew, Tunku’s mother was actually a Mon lady from Burma, who had migrated to Thailand with her father when she was about ten. Some officers even confirmed that Tunku’s mother could speak Burmese.

So perhaps, unknowingly, Malaysia’s founding father had roots tracing back to the very Taline-Mon communities that helped establish the port of Melaka centuries before.

A Joke with a Kernel of Truth

Now allow me to end on a humorous but revealing anecdote—shared during a LYC Camp (a youth leadership camp), where I once met General Tin Oo, former Defense Minister turned founding member of the National League for Democracy (NLD). The General was in high spirits and decided to share a joke.

He asked, “When King Kyansittha conquered Pegu, he went up the Shwemawdaw Pagoda. The place was surrounded by Talines—so how did he come down unharmed?”

Many tried to guess, and then came the punchline:

“Because they weren’t Mon warriors—but Bamar surgeons. You see, they only had one line on their shoulders.”

In Burmese, the word Taline is a homonym: it can also mean “one line.” A silly pun, yes, but jokes often hide deeper social reflections. Ironically, this very same General—once popular and adored—later turned bitter in his speeches, joining the bandwagon of anti-Rohingya rhetoric that swept through some NLD circles.

It’s a pity. A man who once used satire to reflect on historical irony, became a pawn of ethno-political denial.

Conclusion

The tale of the Talines, like many stories of migration and cultural fusion, reminds us that identity is not something fixed or singular. It is layered, plural, and proudly mixed. From Burmese-Mon migrants founding ports in Malaysia, to prime ministers speaking forgotten tongues, our region is richer than the narrow identities we often try to fit ourselves into.

To erase Taline is not just to deny Indian ancestry or sea-borne heritage—it is to amputate a piece of our collective Southeast Asian soul.

Perhaps it’s time we reclaim it.