Before the rise of Bagan or the unification of Burma under the Konbaung dynasty, Lower Myanmar was already home to an advanced civilization. From as early as the 9th century, the Mon Kingdoms stood at the forefront of Indianized cultural exchange, particularly through their deep historical ties with Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and South India. The Mon played a pivotal role in shaping the religious and cultural foundations not only of Myanmar, but also of neighboring Thailand and beyond.

The Hanthawaddy Kingdom: A Golden Era of the Mon

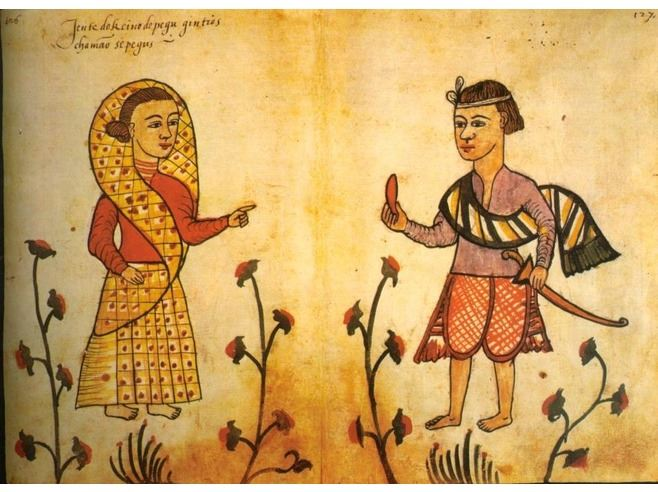

The most illustrious Mon polity was the Hanthawaddy Kingdom (ဟံသာဝတီ ပဲခူး), founded on 4 April 1287, after the decline of Pagan. Hanthawaddy, centered in Pegu (modern Bago), rose to dominate Lower Burma and much of the Tenasserim coast. Key historical phases include:

- Vassalage to Sukhothai (1293–1330) during the Tai expansion.

- The Forty Years’ War (1385–1424) against Ava, leading to military parity and eventual peace.

- A Golden Age (1426–1534) under rulers like King Dhammazedi, who was famed for his diplomacy, religious reforms, and cultural patronage.

- The first fall of Pegu (1534–1539), followed by a brief revival, and the final second fall on 12 March 1552, marking the end of Mon political dominance.

During its height, Hanthawaddy Pegu became a hub of Theravāda Buddhism, international trade, and religious diplomacy. Dhammazedi sent monks to Sri Lanka to reform the Sangha and imported Buddhist texts and relics to reaffirm the purity of the faith. Mon monasteries, written scripts, and canon law heavily influenced Buddhist practice in the region.

Sukhothai and the Tai Appropriation of Mon Culture

Further north, the Sukhothai Kingdom emerged in the early 13th century, when Pho Khun Bangklanghao and Pho Khun Phameung seized power in 1239, wresting control from the Mon. These rulers, though of Tai origin, adopted Mon customs, writing systems, and Theravāda Buddhism—testament to the cultural prestige the Mon civilization held.

The term “Khun” (ขุน), originally a Tai title for a local chieftain, became formalized under Sukhothai’s feudal hierarchy. Despite the political shifts, Mon-Indianized cultural norms endured, and were further disseminated into Thailand and Laos.

Mon Civilization Beyond Borders: Dvaravati and Thaton

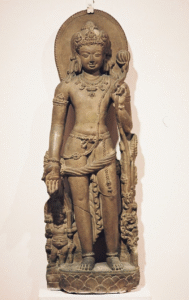

Mon influence extended well beyond present-day Myanmar. Archaeological finds such as Roman oil lamps and early Buddha statues in southern Thailand (Dvaravati region) suggest vibrant maritime and religious connections as early as the 1st–2nd centuries AD.

Chinese pilgrim Yuan Chwang (Xuanzang), in the 7th century, described a unified Mon country from Prome to Chenla (Cambodia)—calling it Dvaravati. Chinese court records further state that Dvaravati was a vassal of Thaton, suggesting the existence of a Mon Buddhist ecumene stretching across much of Southeast Asia. The Mon, therefore, must be seen as a transnational civilization deeply embedded in the Buddhist and commercial networks of early Asia.

Ancient Indian Migration and Tagaung Traditions

While Lower Myanmar attracted Indian traders due to its easy sea access, Upper Myanmar also saw early migration. It is believed that groups migrated overland via Assam and Manipur, eventually reaching areas like Tagaung and Mogok.

According to Burmese tradition, Tagaung was founded by Abhiraja, a prince of the Sakya clan (the Buddha’s tribe) from Kapilavastu, present-day Nepal, in the 9th century BC. His descendants were believed to have ruled northern Myanmar until the city’s conquest by Chinese forces around 600 BC, prompting refugees to found Pagan and Prome further south.

While this narrative may blend myth with history, some historians suggest that the Sakyans, including the Buddha’s own lineage, might have been Mongoloid rather than Indo-Aryan, possibly linking them ethnically with early Myanmar tribes.

The Pyu and Mon: Carriers of the Dhamma

The spread of Theravāda Buddhism in the region is often attributed to missions sent after the Third Buddhist Council in India. Though archaeological continuity is unclear, the Sāsanavaṃsa, a Burmese Buddhist chronicle, suggests an unbroken lineage of teachers in the Mon and Pyu kingdoms preserving the Dhamma.

A key South Indian inscription from Nagarjunakonda (3rd century AD) mentions Buddhist monks traveling to the land of the Cilatas or Kiratas, widely believed to refer to the Mon. The inscription also notes parallel missions to Sri Lanka and other Southeast Asian regions, hinting that Southern India served as the guardian of the Theravāda faith, periodically “re-purifying” Buddhism where it had been diluted by local beliefs.

Conclusion: Mon Heritage and the Foundations of Southeast Asian Civilization

The Mon were more than a regional ethnic group; they were pioneers of Southeast Asian civilization—absorbing, localizing, and transmitting Indian religious, cultural, and administrative traditions. Their influence radiated across borders: into Upper Burma via tradition and migration, into Sukhothai and Ayutthaya through cultural assimilation, and into the Buddhist heartlands of Sri Lanka and South India through sustained religious dialogue.

Even after their political eclipse in the 16th century, Mon contributions in script, language, Theravāda orthodoxy, and statecraft remained embedded in the DNA of Myanmar and beyond.

In remembering the Hanthawaddy Kingdom and its legacy, we recall a civilization that stood as both a recipient and a transmitter—a bridge between India and mainland Southeast Asia, between Buddhist faith and political sovereignty, and between the past and the cultural present.