U Ye Htut correctly identified the original builders of this bridge as Pashtun and Ottoman Turkish POWs—captured during the First World War and sent to British Burma as forced laborers. These prisoners, mainly from what is now Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Turkey, were made to work on major infrastructure projects, including the Kalaw-Aungban railway and the Meiktila Lake excavation.

Their contribution to Myanmar’s colonial infrastructure was immense—and tragic. Many of them died from tropical diseases, exhaustion, or malnutrition. They were buried in cemeteries near Meiktila and Kalaw. One mosque they built inside a prison near the royal palace compound was later destroyed by the current military junta—a symbolic erasure of their presence and faith.

Local tradition maintains that after completing the railway segment near Ingyin, some workers settled permanently in the area. Their descendants opened tea shops, textile stores, garages, and even tour guide offices in Kalaw. They brewed distinctive milk tea, sold flavorful snacks, and contributed to the town’s vibrant mixed culture.

The cemetery near the Ingyin football field, nestled on a slope by the stone bridge, may house the remains of some of these POWs. Today, its gates are often closed, the graves unvisited, and their stories slowly fading.

The Silenced General and Myanmar’s Military Legacy

Another erased chapter is that of General Smith Dun, Myanmar’s first post-independence Chief of Staff. A Karen by ethnicity and a Sandhurst-trained officer, he embodied professionalism and discipline. Yet, in 1949, he was forced into retirement by General Ne Win, simply for being Karen in an increasingly Bamar-dominated army.

Smith Dun’s daughter became a teacher at Kalaw’s Convent School—another thread of history mostly unknown to the youth of Myanmar. Meanwhile, the military—rooted in Japanese fascist ideologies from WWII—continued to build its identity on selective narratives, crediting its founding to a narrow group of “Thirty Comrades” while erasing others, particularly the roles of ethnic minorities and leftist revolutionary movements.

Why These Histories Matter

Myanmar cannot move forward without acknowledging the full, unfiltered past. Stories of Turkish POWs, Pashtun laborers, and suppressed generals are not just academic trivia. They reflect systemic erasures that helped construct an exclusive nationalism—one that feeds current ethnic conflict and centralist authoritarianism.

Understanding these stories—such as the quiet bridge at Inpyin—is not about nostalgia. It is about building a political and cultural future grounded in truth. The dream of a federal union cannot survive on myth-making and militarized propaganda. It must begin by confronting uncomfortable facts: that many who built this land and defended it, died without thanks.

As Maung Maung Ni poignantly puts it: “The people are always in the audience, watching the show. But they must not be asked to keep silent forever.”

MMNN Notes:

Inpyin and Kalaw’s Ottoman POWs were part of a broader forced labor network under British rule. Their cemeteries, though crumbling, still stand as testaments.

General Smith Dun’s biography is available in English, Burmese, and Karen languages, yet remains excluded from most national curricula.

The Inpyin Bridge is still standing. Its craftsmanship—stone-cut precision without cement—is a living classroom of forgotten sacrifice.

Ye Htut, once praised for investigative insight, has lost credibility due to his partisan manipulation of social media and state narratives.During World War I, the British interned thousands of Ottoman soldiers, many of whom were Turkish, in camps in Burma (now Myanmar) after capturing them in the Middle East. Two of the main camps were in Thayetmyo and Meiktila. Many of these prisoners of war died in captivity due to disease and other factors, and their remains are interred in war cemeteries in Myanmar.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown:

- Capture and Internment:Following the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in the Middle Eastern campaigns of WWI, the British captured thousands of Ottoman soldiers, including many Turks. These prisoners were then sent to British-controlled Burma (Myanmar), where they were held in camps.

- Camps in Burma:The main camps were located in Thayetmyo and Meiktila. The camp at Thayetmyo housed around 3,600 prisoners, while the one at Meiktila held approximately 10,000.

- Prisoner Treatment and Conditions:While some sources suggest the prisoners were generally treated well, there were also reports of harsh conditions, including disease outbreaks and forced labor. One particular issue was the development of pellagra, a vitamin deficiency disease, among the Ottoman prisoners due to a specific “non-European” diet provided by the British.

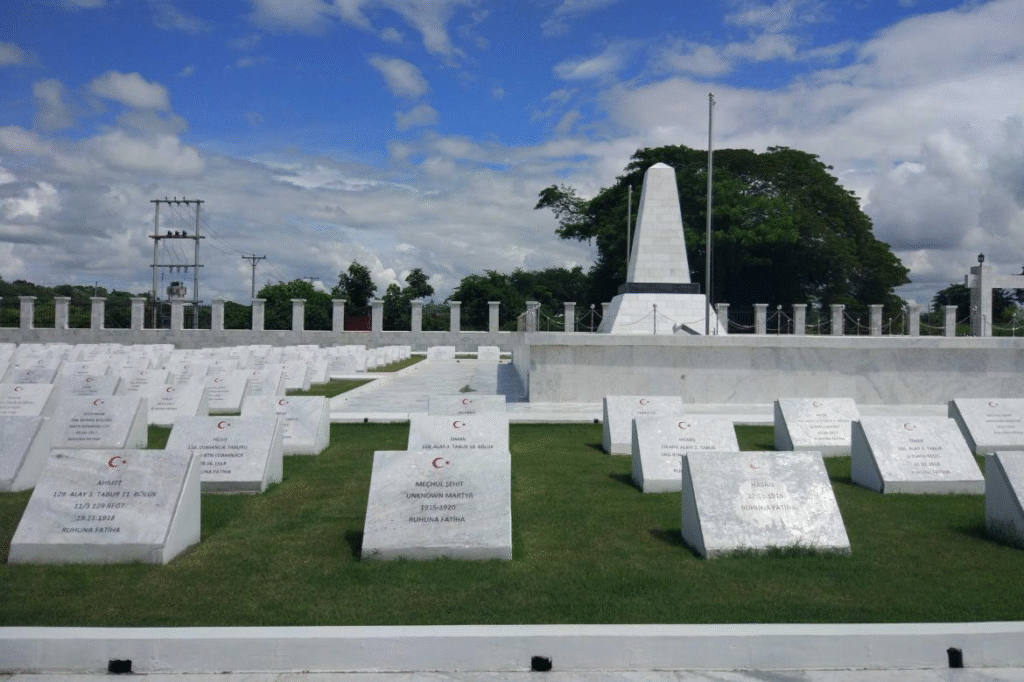

- Cemeteries and Memorials:Many prisoners died in captivity, and their remains were buried in war cemeteries in Myanmar, notably in Thayet and Meiktila. The Turkish government has since restored the cemeteries and erected memorials to honor the fallen soldiers.

- Ongoing Remembrance:The Turkish government has made efforts to maintain the cemeteries and commemorate the prisoners, highlighting their contribution to the development of Myanmar while in captivity and fostering relations between the two countries. The colonial-era cemeteries honouring Turkish POWs

Ottoman Prisoners of War in Burma

During World War I a unique venue of interaction between the Ottoman

empire and Southeast Asia came into existence when Britain established

detention camps in Thayetmyo and Sumerpur in Burma (Myanmar) for

Ottoman prisoners of war. The Ottoman archives contain voluminous

records about the communications between Ottoman and British au-

thorities as well as between the captives and their families which were

transmitted to warring parties through the mediation of neutral coun-

In World War I, Meiktila and Thayetmyo became the unlikely final resting places for hundreds of Ottoman Empire troops sent to Burma by the British after being captured during fighting in the Middle East.

By JAMES T DAVIES | FRONTIER

IT’S A little-known fact that the British interned thousands of Turkish prisoners of war in Burma during World War I, and that hundreds of these citizens of the Ottoman Empire never returned home to the nation that in 1923 became the Republic of Turkey.

Their final resting place is one of two war cemeteries near the camps where they were sent following their capture in the Middle East after WWI began in 1914.

I first heard about the cemeteries over tea with a political activist in Meiktila last year as we discussed the communal violence that convulsed the dusty central Myanmar market town in March 2013.

He said a rumour had swept the Mandalay Region town ahead of the violence that the ruined cemetery was to be restored and a mosque built at the site.

The colonial-era cemeteries honouring Turkish POWs