Author: Bo Aung Din

Dear Nan,

Thank you for your kind letter. I’m relieved to know you’re not angry anymore, and I understand your decision to stay longer with your aunts. Their grief is deep—their husbands handed cruel prison sentences merely for political discussion. They weren’t criminals, nor had they participated in violence. Yet, here they are, suffering behind bars.

Ours is a country where distributing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights can land you in jail. Imagine! A document adopted by the United Nations on December 10, 1948, as a global standard of dignity and freedom—treated as contraband in Myanmar.

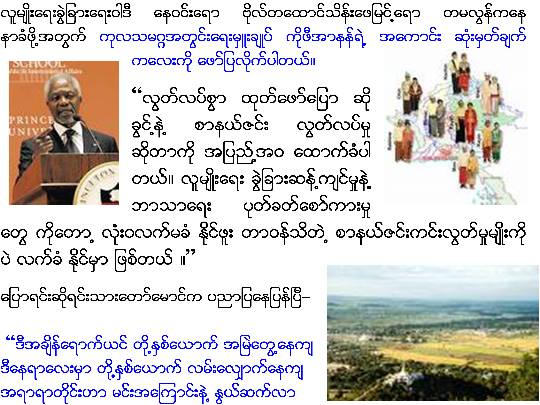

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan once said:

“Human rights are foreign to no culture and native to all nations. It is a mirror that flatters us and shames us, that bears witness to a record of progress for parts of humanity while revealing a history and reality of horrors for others.”

He reminded the world that people do not oppose human rights—it is their leaders who do. In Myanmar and other ASEAN nations, dictators dismiss human rights as a “Western concept” merely to mask their repression.

Compared to the pain those families endure, our temporary separation is bearable. You are always close in my thoughts. Even now, our son is playing a song we both love, teasing me as I write to you. It’s comforting.

Do you remember when we first introduced him to Hti Saing’s songs? He called them “black-and-white songs”—outdated and boring. But look at him now—searching through Burmese shops for VCDs of old music. Though he was born abroad, he carries the blood of Burma—Bamar from me, Shan from you, and a shared Burmese spirit that binds us to our Chinese and Muslim brothers and sisters. Only after leaving home did I understand how strong those ties truly are.

Nan, we’ve had our share of arguments. You once told me—citing a psychology book—that every household needs a dominant partner, and that gender equality leads to more divorces in the West. Maybe there’s a sliver of truth in that. But let’s talk seriously about rights and injustice.

If there were a Guinness World Record for repression, Myanmar’s military rulers would surely win. Imagine—a man was jailed and later died in detention simply for using an unlicensed fax machine. That was Leo Nichols, unofficial consul for Norway and several other countries, jailed in 1996. That belongs in Ripley’s Believe It or Not.

Gender discrimination? Successive military governments never appointed a single woman as minister or deputy. Yes, there are whispers that generals’ wives—like Daw Kyaing Kyaing—wield power behind the scenes, deciding promotions, business deals, and study tours. But if those stories are true, they expose an even deeper dysfunction.

Our arguments often reflect wider truths. Our son’s recent choice of music—the song “A Shan Who Visited Mandalay”—shows the feelings of being an outsider. That song echoes the discomfort of a Shan arriving in the Bamar heartland. Yet, the singer and composer, both Shan, found success in Mandalay. Dr. Sai Kham Leik became a medical doctor, earned a master’s degree, and married a Bamar woman. That’s the real Burma—a web of shared lives.

Now, our son plays your favorite: “The Nature’s Children.” Perhaps it’s his quiet plea for peace, a ceasefire to our daily tensions. I believe the root cause of conflict—whether personal or political—is human ego: the desire to dominate, the fear of being less.

Remember our son’s school incident? He kicked a Burmese Muslim classmate. The boy had called him a “mixed blood”—Bamar and Shan. That insult struck hard. He’d heard it from both sides: your relatives calling him “Bamar Poke Kalay,” mine calling him “Shan Pae Poke.” His identity—supposed to be a bridge—became a battleground.

But the fault was ours. Adults taught them these slurs. That moment in 1972 coincided with General Ne Win’s infamous speech at the BSPP conference, preparing for the citizenship law. He called Burmese Muslims “mi ma sit, pha ma sit”—bastards. That speech sowed deep seeds of hate.

Ne Win’s failures led him to scapegoat minorities. When socialism collapsed, he blamed others. In 1967, it was the Chinese. By 1972, it was Indians and Muslims. To my Burmese Muslim friends, I apologize. Reopening this wound is painful, but necessary. In Burmese, we say: only if we find the diagnosis can we find the cure.

The media became complicit. Even our respected Burmese Chinese friends had to conceal their heritage. Some claimed to be “pure Bamar” out of fear. Ne Win himself was of Hokkien Chinese descent.

Contrast that with Bogyoke Aung San. He sought unity. He invited all nationalities to Panglong. Today’s generals try to erase that legacy. Nan, I remember your bravery. When the school headmaster raised the incident, you spoke up. You explained the origin of those hateful words and blamed Ne Win by name. I still admire that moment.

And now, the last memory that lingers: you showing me the newspaper column by Thein Pe Myint of Bo Ta Htaung, my favorite journalist. He echoed Ne Win’s slur, “Kala Dain,” contrasting “good old Indians” with “bad new ones.” We were both furious. We swore off his work forever.

Kofi Annan said:

“We all fully recognize and respect freedom of the press and expression but it must be coupled with press responsibility. Inciting religious or ethnic hatred in this manner is not acceptable.”

Annan was right. Press freedom must never be a license to hate.

Yours with love,

(Ko Tin Nwe)

Bo Aung Din