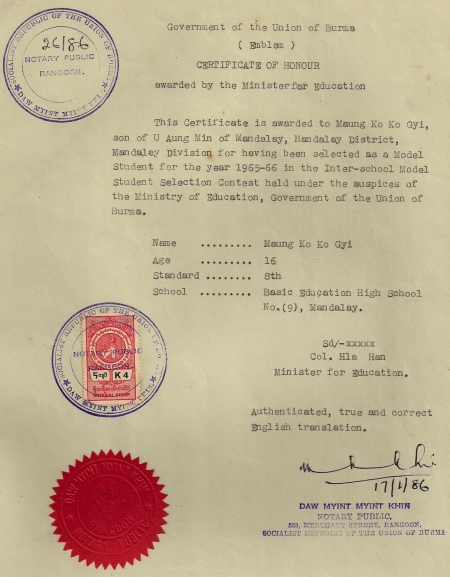

1966. I was just sixteen.

Alongside my friend Than Win (now Dr. Than Win, former Rector of the University of Medicine Mandalay and later an NLD MP), I was selected as a Luyechun (Outstanding Student) from Mandalay. We were both from St. Peter’s High School and had the distinction of being selected five times each. He was short and plump; I was tall and thin. At the camp, people teased us as the Burmese cartoon duo “Pho Wa and Ingar Jaw” or likened us to R2-D2 and C-3PO from Star Wars – a strange pair, but inseparable.

We were part of a national program initiated by General Ne Win’s Revolutionary Government to mold top-performing students into loyal socialist youth leaders. The camps, held in scenic places like Nga Pali’s Shwe War Chaing and Inlay’s Khaung Daing, were meant to indoctrinate bright young minds. But instead of being brainwashed, I began to question.

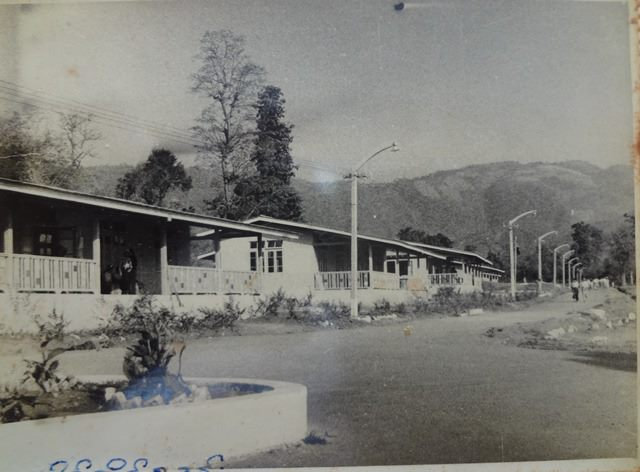

LYC Camp in Inlay. I took this photo with my Yashica camera.

The Expired Medicine Incident and U Win Tin

During my early school years, I purchased a bottle of Waterbury Compound, a vitamin syrup, from a government-run People’s Drug Store. After taking it, I suffered severe stomach upset and consulted our family doctor, Dr. Mazunda, who discovered that the medicine had expired and had black deposits inside.

I wrote a letter of complaint to Hantharwaddy, the state-run newspaper in Mandalay. When it wasn’t published, I called their office. Eventually, I was connected to the Chief Editor U Win Tin, who would later become a leading figure in the NLD.

Despite his reputation, U Win Tin gave unsatisfactory responses. He claimed there was no space for my letter and said my complaint was a “sensitive issue.” I pointed out that his newspaper regularly published mundane complaints about potholes and broken pipes. I had provided my name, registration number, address, and even kept the receipt and the bottle. But he still refused. When I asked whether he followed the model of editors in the Soviet Union, who escalated unresolved public issues to authorities, he said no.

I raised this incident again during our Luyechun camp session, illustrating how government-appointed editors were ignoring serious health hazards while amplifying trivial municipal problems.

Dr TW was at the front, I was far away behind and half covered. Col. Tin Oo (later NLD)

BSPP CEC and the Appointed Youth Leaders

At one of our Luyechun camps, BSPP CEC members including U Min Htwe were preparing to launch the Lanzin Lu Nge (Youth Cadre Organization). They explained that youth leaders would be appointed from above.

I stood up and objected. I said that appointment from above fosters sycophancy, stifles genuine feedback, and creates a culture where leaders hide problems to protect their positions. I gave the U Win Tin incident as an example, saying that if even a chief editor did not dare to publish the truth, how could we expect honesty from youth leaders who fear their superiors?

U Min Htwe dismissed my argument in front of the class, calling it irrelevant. But the tension was clear.

Challenging Their Ideology

In one lecture, U Min Htwe claimed that mission schools had forcibly converted students to Christianity. I stood up and said:

“My friend Than Win and I are from St. Peter’s. He’s still Buddhist, and I’m still Muslim. We weren’t forced to convert or change our names.”

Another time, while discussing historical systems of governance, I questioned the idea that socialism was the final stage of human progress. I said:

“According to both Buddhism and dialectical materialism, everything is impermanent. Socialism too will decay one day. We must imagine and prepare for a better system.”

His reaction was one of outrage. But I had made my point.

In another session, U Min Htwe said:

“In capitalism, the boss is always right. In socialism, the worker is always right—even if he is wrong.”

No one dared respond—except me.

“We should look at things fairly. Yes, we should support workers, but if they’re wrong, we must say so. Otherwise, we’re just replacing one injustice with another.”

He snapped back:

“In socialism, the worker must be right—right or wrong!”

Yet when workers protested in reality, Ne Win’s army shot them down.

Marked as a Dissenter

After one such debate, a BSPP Central Committee member unexpectedly visited my dormitory at Tagaung Combined Luyechun Camp at dawn. He tried to explain away the 1962 student massacre, saying the government was inexperienced at the time. It was only later I understood: I was being monitored. I had been marked.

Though they had promised that Luyechuns would become national leaders, I was never offered any leadership role. When Lanzin Lu Nge was finally launched, I was only a regular member—and I never participated in their activities.

A Final Reflection

I was just a teenager, full of questions. But those questions unsettled seasoned ideologues and top editors alike.

While others from our camp became ministers, generals, rectors, and professors, I took a different path—as a doctor, a witness, and a quiet dissenter.

I never made it into the Socialist leadership. But I kept something far more valuable: my integrity and my voice.

Rohingya Dr Kamal Hussein got LYC from BESH Maungdaw studied at Institute of Medicine 2, Myanmar and got MSc Computer Science from UKM, National University of Malaysia. He is now in Australia.

Asso. Prof. Daw Win Win Myint, Chief Physician. Medical Ward. Muslim Free Hospital. YANGON.

Read also: