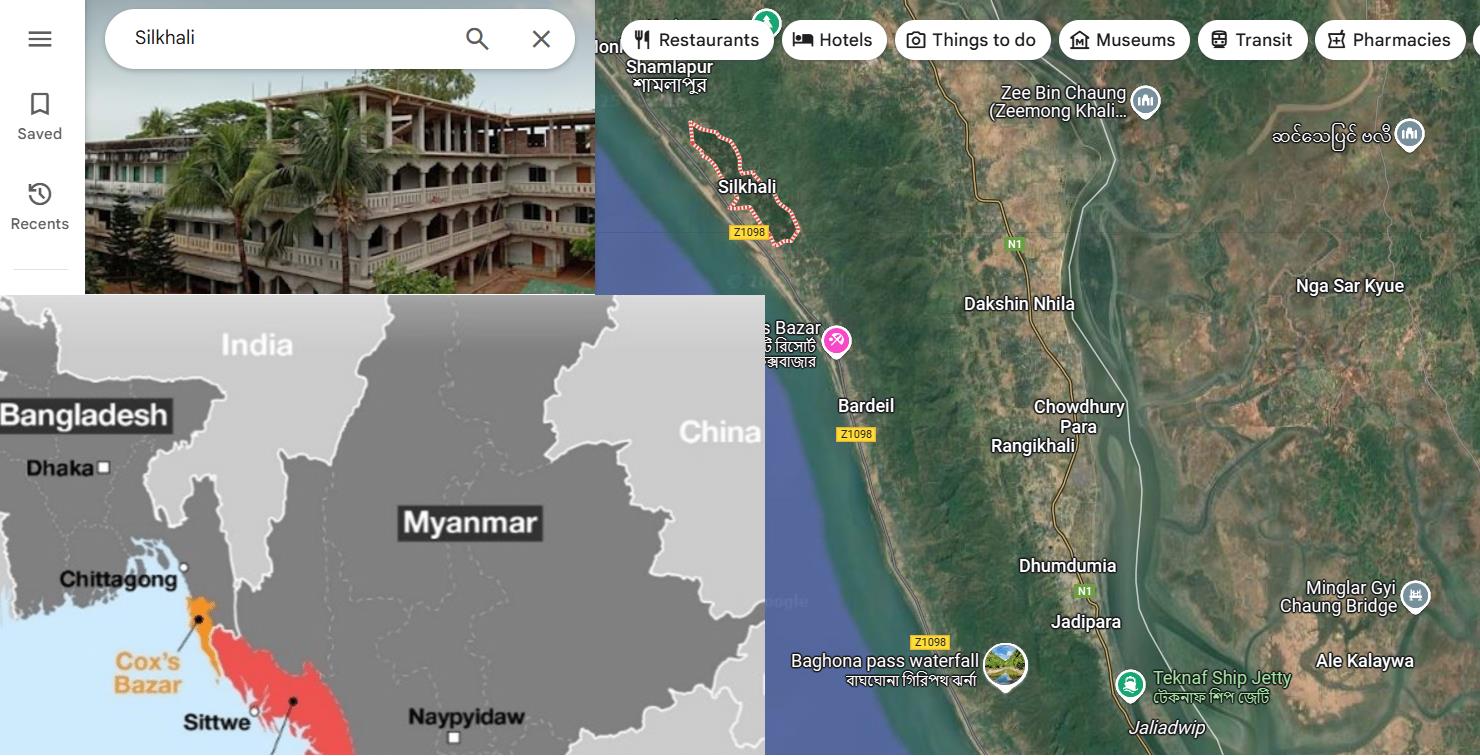

Is Silkhali Corridor Luring Bangladesh into a Proxy War Trap?

Rakib Al Hasan

Publish: Monday, 28 April, 2025 10:18

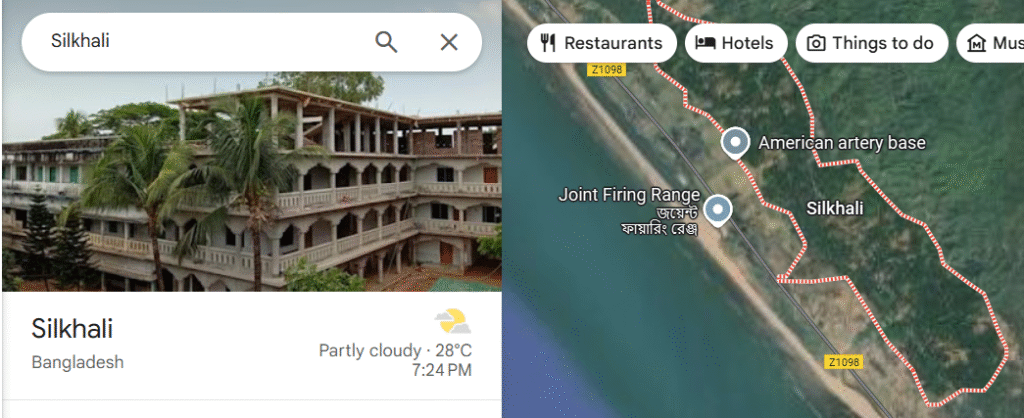

(My addition: Look: There is an American Artery base there in Silkhali.)

Sometimes wars arrive not with a crash of artillery but with a silent procession of well-meaning convoys. In south-eastern Bangladesh, near the humid forests of Teknaf and the forgotten banks of the Naf River, a quiet but deadly script is unfolding — one that could drag a fragile nation into a proxy war not of its choosing and whose fires it may never be able to extinguish.

At the centre of this slow-burning crisis lies the ‘Silkhali Corridor’, a proposed humanitarian supply route into Myanmar’s crumbling Rakhine State. Officially, it is to provide relief — food, water, medicine — to desperate civilians caught in the crossfire between the Myanmar military junta and the surging Arakan Army (AA). Unofficially, it risks becoming something far more dangerous: a vital artery for a United States-backed insurgency aiming to topple Myanmar’s Chinese-aligned regime, using Bangladesh’s soil as the staging ground.

To the casual observer, the stakes seem small — a few aid shipments crossing a dense border forest. But the stakes are existential. Bangladesh, a nation already stretched by hosting 1.2 million Rohingya refugees, besieged by economic pressures and navigating a delicate regional diplomacy between China, India and the United States, now faces a strategic gamble that could shatter its stability, sovereignty and future.

If Dhaka approves the Silkhali Corridor in its current form, it will do more than allow humanitarian trucks to cross the border. It will sign an unwritten pact of participation. The corridor will inevitably become a logistics lifeline for rebel groups seeking to overthrow the junta. It will draw retaliatory fire across the border. It will invite the complexities of insurgent politics into Bangladesh’s already sensitive south-eastern hills. And it will set Bangladesh on a collision course with a collapsing neighbour armed by Beijing and increasingly willing to lash out in desperation.

Meanwhile, Myanmar’s junta, led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, is losing ground rapidly. The Arakan Army, now controlling 90% of Rakhine State, is no longer merely an ethnic insurgency but a de facto government-in-waiting. Sittwe and Kyaukpyu — the last bastions of junta control — are under siege. To Washington, this presents an irresistible opportunity: by empowering the AA and allied groups like the Chin National Front (CNF), the United States can weaken China’s strategic hold over the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal without deploying a single American soldier.

Bangladesh, however, sits directly in the blast radius of this geopolitical gamble. Already there are ominous signs that the ground is shifting. In April, armed Arakan Army fighters openly crossed ten kilometres into Bangladesh’s Bandarban district and staged a military-style festival — waving their flags, displaying their weapons and receiving the silent complicity of local politicians and ethnic leaders. Video footage showed Bangladesh’s Border Guard (BGB) forces standing by, neither intervening nor objecting. It was not an isolated incident. It was a signal — a signal that the Arakan Army no longer respects the border and that parts of Bangladesh’s ethnic minorities may no longer see Dhaka as their only authority.

The depth of this infiltration should concern policymakers in Dhaka. The southeastern Chittagong Hill Tracts have long been Bangladesh’s most volatile internal frontier. It took decades of peace deals, demobilisation and painful political negotiation to calm the insurgencies there. Now, with a few festivals and a few flags, those hard-won gains are being quietly undone. Ethnic Marma, Chakma and other hill communities, historically alienated from Dhaka’s plains-dominated politics, are being courted by the Arakan Army’s message of autonomy and ethnic solidarity. In the empty promises of insurgent rhetoric, they find echoes of old grievances — grievances that could easily flare into renewed separatism if fanned by foreign support and military logistics.

The Silkhali Corridor, if opened without extreme caution, risks becoming the pipeline that feeds not only Rakhine’s insurgency but also Bangladesh’s own internal fragmentation. The Arakan Army is not a neutral humanitarian actor. It is a military organisation implicated in serious human rights abuses, particularly against Rohingya Muslims. Rohingya survivors in Cox’s Bazar remember AA fighters not as allies but as executioners — accused of participating in village burnings, killings and ethnic cleansing operations in collaboration with Myanmar’s military. By enabling the AA now, Bangladesh would not merely be enabling a rebellion against the junta. It would be empowering a force historically hostile to the very refugee community Bangladesh sacrificed so much to protect.

There is also the unspoken truth that Washington’s strategic calculus has little room for Bangladesh’s security dilemmas. For American planners focused on the Indo-Pacific, Bangladesh is a logistical node, a means to an end. If Silkhali becomes the new conduit for a guerrilla war against Naypyidaw and if Bangladesh’s south-eastern districts become collateral damage, it will be viewed in Washington as an acceptable cost. After all, no American soldiers will bleed on those muddy hills. It will be Bangladeshi forces, Bangladeshi civilians, Bangladeshi sovereignty, that will pay the price.

History offers some brutal lessons in this connection. In the 1980s, Pakistan’s tacit support for the Afghan mujahideen, at America’s behest, brought not only the collapse of the Soviet-backed Afghan regime but also decades of internal extremism, insurgency and terror that Pakistan could never fully contain. In the 1970s, Southeast Asian states that permitted foreign powers to use their soil as staging grounds for insurgencies often found themselves engulfed in spiralling wars they could neither control nor end. Bangladesh’s leaders must not delude themselves into believing that “limited” logistical cooperation can be neatly compartmentalized. Proxy wars are by nature infectious.

Even if the initial aid shipments are restricted to food and medical supplies, the pressures for mission creep will be immense. Insurgent forces, emboldened by early victories and desperate for sustainability, will inevitably demand more. “Humanitarian convoys” will become “technical assistance missions.” Safe corridors will become supply routes. Border skirmishes will become full-blown retaliation as Myanmar’s desperate generals lash out across the Naf. Already increasingly aligned with China and Russia, the junta will view Bangladesh not as a neutral neighbor but as an enemy collaborator.

And China, watching closely, will not sit idly by while a vital strategic corridor — including key energy pipelines through Kyaukpyu — falls into instability. Beijing’s interventions could take many forms: diplomatic, economic, covert. None of them would favour Bangladesh’s long-term autonomy.

Domestically, the consequences would be equally devastating. A south-eastern insurgency would force Bangladesh’s military into a grinding, endless counterinsurgency it is neither equipped nor politically prepared for. Economic growth, already fragile in a post-COVID global order, would nosedive. Investment would dry up. Social tensions between hill communities and Bengali-majority areas would reignite old fires. The carefully crafted international image of Bangladesh as a rising moderate Muslim democracy would erode into yet another narrative of instability and conflict.

The tragedy is that none of this is inevitable. There is still a path for Bangladesh to assert its sovereignty and avoid entrapment. It requires saying no — clearly, unequivocally and immediately — to any form of unilateral militarised corridors. Humanitarian aid, if provided, must be channelled through neutral, international actors like the Red Cross or UN agencies, with full transparency and no parallel insurgent pipelines. The Bangladesh Armed Forces must reassert visible control over the border regions, not merely as border guards but as guardians of national integrity. Local political leaders must be held accountable for fraternising with foreign armed groups. And most importantly, Dhaka must engage in urgent, high-level diplomacy with both Washington and Beijing, making clear that it will not serve as a pawn in any new Great Game.

There is courage in compassion but greater courage in caution. Bangladesh can still offer humanitarian aid to suffering civilians without surrendering its future to foreign designs. It can still defend its moral standing without becoming a logistical pawn in someone else’s war. But time is running short. The corridors are being drawn. The insurgents are emboldened. The generals in Naypyidaw, desperate and cornered, are already preparing their next moves. And the storm gathering over Silkhali will not wait forever.

In the end, Bangladesh must ask itself the most fundamental question a nation can face: will it be the master of its own destiny — or merely another battleground in someone else’s war? The choice is still Dhaka’s to make. But every day of silence brings the storm closer. And history, as always, will remember those who saw the fire coming — and those who walked straight into it.